Even for the vindictive world of hacking, it was petulant stuff. Ryan Cleary's enemies in Anonymous, the notorious hacking collective whose exploits have embarrassed corporations and governments, planned to send scores of dildos to the Essex house where the teenager lived with his parents.

Then they became more ambitious. "Fuck him over, send pizzas to his house, hire strippers, spam his emails, hack his shit, prank call his house, that's what he deserves, in fact he would do the same thing to us without feeling like a moral fag [naive prude]," one suggested.

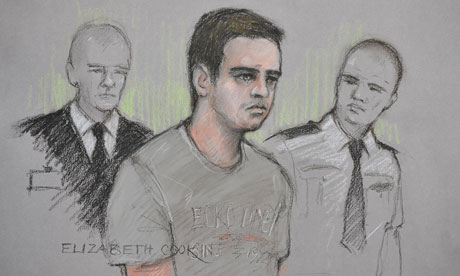

But what started out as a childish spat – one that says much about the egotistical, often tribal, nature of modern hacking – ended last week with Cleary's arrest for allegedly trying to bring down numerous targets, including the website of the Serious Organised Crime Agency.

Scotland Yard might never have come knocking if, in early May, Anonymous had not felt compelled to warn its members on its AnonOps site: "Our network has been compromised by a former IRC [internet relay chat] operator and fellow helper named 'Ryan'. He decided that he didn't like the leaderless command structure that AnonOps network admins use. So he organised a coup d'etat."

Anonymous, which uses as its symbol the Guy Fawkes mask made famous in the film V for Vendetta, believed Cleary, 19, had stolen passwords and targeted the servers it used to run its websites.

Someone identified as "Ryan" boasted about what he had done, telling a technology website that he and his allies had formed a new splinter group because they were disgusted with how "PR-hungry" Anonymous had become. Hacking into the Anonymous system had been "regrettable but necessary", he said.

The revelation that the hackers' security had apparently been compromised by one of their own triggered anguish. "Ryan posted IP addresses of all the users, including me and I'm innocent, I just watch operations I don't get involved," one member posted online.

Days later, someone hacked the website of the computer games manufacturer Eidos and made it appear that it had been defaced by a group called Chippy 1337 – whose members, it was claimed in an online calling card, included "Ryan Cleary". Then, in May, the nuclear option: Cleary's home address, telephone number and IP address were posted on an Anonymous-linked website. From that moment, he was living on borrowed time.

Even some within Anonymous were aghast that Cleary's personal details had been published. As one Anonymous member posted online: "Ryan pulled a major dick move, but leave the bastard alone. Karma gets everyone in the end."

Cleary's arrest has seen him transformed into two distinct characters in the public imagination. To some he was public enemy number one, a hacker of skill and menace who allegedly had the power to bring businesses to their knees. To others he was simply a computer geek who had, perhaps unwittingly, been caught up in the strange world of "hacktivism", a subset of hacking that targets large companies and governments, not for money but for a cause. Some drew comparisons with another man, Gary McKinnon, wanted in the US for allegedly hacking into the Pentagon and Nasa while searching for evidence of aliens.

In the immediate aftermath of Cleary's arrest, attention quickly turned to his possible links with another hacktivism group, Lulz Security, which has close ties with Anonymous. LulzSec responded by tweeting: "Clearly the UK police are so desperate to catch us that they've gone and arrested someone who is, at best, mildly associated with us. Lame."

The partial denial cannot easily be disproved. Hacktivism is decentralised. With collectives' members spread over time zones and continents, and only infrequently joining together to launch attacks co-ordinated by a handful of core operatives, linking them to a particular event or attack is often impossible.

For the groups, this can be an asset. "Leaderlessness would seem to be their strength," said Ray Bryant, the chief executive of Idappcom, an internet security company. "Cut off one head and they will grow another. Arresting one person in Essex will create a martyr to the cause." But the lack of hierarchy and discipline encourages erratic behaviour among members. Anonymous recently urged its supporters to report mass sightings of UFOs, with the result that bogus stories about alien-craft sightings were reported on television stations as far afield as Russia and Argentina.

Many within Anonymous, which made its name by hacking the Church of Scientology and last year attacked PayPal for refusing to process payments to the WikiLeaks website, were appalled at the childish stunt.

But then, internal disputes among hacking collectives are common. Anonymous itself was formed by a breakaway faction from the group behind 4Chan, the online message board set up to share Japanese manga art. 4Chan was behind the phenomenon of "rickrolling", where people following an online link apparently relevant to what they were searching for would find themselves instead viewing a video of Rick Astley singing Never Gonna Give You Up.

Following their self-imposed exile from 4Chan, Anonymous's founders eschewed such frivolous activities, painting themselves as a countercultural force, their confidence expressed in the slogan: "We are Legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us."

By contrast, LulzSec, whose website plays the theme from Love Boat and has a monocled cartoon bon viveur as its avatar, is more flamboyant.

Having shot to prominence by releasing confidential details of US X Factor contestants, LulzSec has been blamed for attacks on Sony, Nintendo and the NHS. In one celebrated incident, it defaced the PBS news website so that it carried a fake article reporting that the deceased rapper Tupac Shakur was living in New Zealand. In the last month, the group has claimed responsibility for shutting down the US Senate and CIA websites.

To celebrate its 1,000th tweet – the method by which it informs its 250,000 followers that it has launched a successful attack – LulzSec recently posted a manifesto explaining why it carried out hacks for fun (or "lulz"): "Watching someone's Facebook picture turn into a penis and seeing their sister's shocked response is priceless. Receiving angry emails from the man you just sent 10 dildos to because he can't secure his Amazon password is priceless. You find it funny to watch havoc unfold, and we find it funny to cause it."

But while the anarchic appeal of both Anonymous and Lulz is earning them a global following, experts warn that their activities run the risk of obscuring the real threat posed by cyber-espionage and online organised crime.

Indeed, much hacktivism is not even "hacking" in the conventional sense – that is, the illegal retrieval of confidential information from protected computer systems. Rather, it takes the form of "distributed denial of service" (DDoS) attacks, whereby software loaded onto a series of computers inundates a website with traffic, causing it to crash. Such attacks are not difficult to mobilise: the "malware" needed to carry them out can be freely downloaded from websites, while YouTube videos are available to explain how to install it. Significantly, Cleary is charged with conspiring to launch DDoS attacks, rather than hacking, suggesting he may not be the computer genius that some claim. His arrest, however, will certainly further the hacktivism cause.

The success of a DDoS attack depends on building a powerful brand. The more supporters the handful of people at the centre of a hacktivism collective can reach out to, the more computers they can utilise for an attack. In Operation Payback, a co-ordinated assault on anti-piracy organisations launched late last year, Anonymous amassed a large army with impressive speed.

According to the internet security company Imperva, on 5 December last year the software needed to launch the Operation Payback attack was downloaded 306 times. Three days later, more than 10,000 computers were downloading the software as Anonymous put the word out.

"There has been an increase in attacks; we have seen very recently an increase in activity from LulzSec," said Imperva's co-founder, Amichai Shulman. "But I don't think it's proportionate to the media attention it is getting. I don't think these people are that sophisticated. In many of the attacks, they have been using standard hacking tools."

That much hacktivism is rudimentary, however, is itself a cause for alarm, according to experts. "Over the last couple of months we've seen a number of incidents starting with the break-in at [online security company] RSA, Lockheed Martin, Sony, the IMF; these are all big and respectable enterprises that had good security practices in place and yet it was relatively easy for the criminals to get in and steal the information," said Mickey Boodaei, chief executive of Trusteer, a company that specialises in providing secure web access.

Experts warn that the competition to launch ever more audacious hacks creates an inflationary spiral. "I've never known a year like this: it's been predicted that very soon a big corporate will be brought down," said Professor John Walker of the Isaca security advisory group, which advises corporations on online protection.

For Walker, history is turning full circle. "It's going back to the early days of virus creation, when people were doing these things to announce their presence – sending little cards cascading across computer screens to say "I've been so clever, I've infected your computer." What's happening now is about boastfulness; it's about doing something for the sake of it, because they can."

Sometimes the boasts are hollow; several claims surrounding hacktivists have been exposed as false. Last week it was reported that LulzSec had obtained the 2011 UK census data and was planning to post it on the Pirate Bay, the online shopping centre for confidential information. The Office of National Statistics poured cold water on the story and LulzSec denied involvement, stating in a Twitter update: "Don't believe fake LulzSec releases unless we put out a tweet first."

Even the false rumours can be useful to the hacktivism cause, helping spread fear and mayhem across the internet.

Dr Simon Moores, chair of the International eCrime Congress, a body that regularly receives briefings from law enforcement agencies on how to tackle hacking, suggested the internet was facilitating a "post-modern, crowd-sourced equivalent of The War of the Flea – Robert Taber's influential text on guerrilla warfare. "What the Red Brigades was to the 70s, LulzSec may be to the early 21st century," Moores said.

For its part, LulzSec is sufficiently self-aware to recognise that the Darwinian nature of hacking, with rival groups vying to outdo each other, means it will soon be eclipsed by a more outlandish outfit keen to grab some glory. "You'll forget about us in three months' time when there's a new scandal to gawk at," it acknowledged on its website, concluding philosophically: "This is the internet, where we screw each other over for a jolt of satisfaction."

Perhaps predictably, LulzSec itself was temporarily taken down on Friday morning, apparently by an ex-military hacker known as the Jester who has waged a long-running battle against both Anonymous and LulzSec.

The Jester said he did it "for the lulz". As Cleary discovered, hackers are happy to eat their own.