Britain's economy must undergo a cultural revolution to prevent manufacturing losing so many school-leavers and high-flying graduates to the City, the business secretary said on Wednesday.

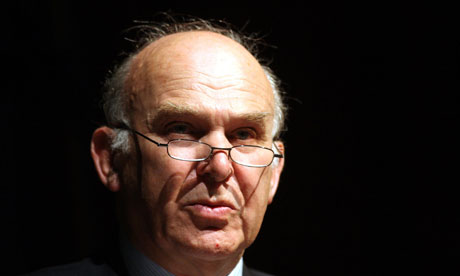

Vince Cable said youngsters considering their adult vocation still held negative views of a manufacturing sector that employs 2.6 million people and contributes more to the economy than financial services, generating 11% of GDP. "In order to get the population of highly motivated, good, young people coming in [to manufacturing], we have to change the perception that it is technical, noisy and dirty," he said, adding: "At a graduate level there is a cultural issue, and it is also true of school-leavers."

Speaking during a visit to the Mini factory in Oxfordshire as part of the See Inside Manufacturing programme, in which industrial companies open their doors to schools, Cable said the problem of recruitment was a frequently heard refrain among employers. "The issue they raise is where do they get the trained people from, as well as the importance of apprenticeships and career engineers."

Citing the example of his son's peers, Cable said the Square Mile was still a major draw for graduates. "My younger son was a very bright Cambridge mathematician and a heavy percentage of his peer group ended up in the City instead of in science or manufacturing."

Cable's comments are the latest contribution to a government drive to boost the role of manufacturing in the UK economy. The chancellor called for a "march of the makers" in his budget speech in March, but concerns over the current generation of engineers and scientists also extend to the next one.

Garel Rhys, emeritus professor at Cardiff University business school, said teachers would be key figures in Cable's public relations drive. "The perception of the manufacturing industry with graduates has been very poor for the best part of 40 years. Teachers never saw themselves as recruiting sergeants for industry."

The 71-year-old Rhys, who grew up in the coal and steel region of Glamorgan, added that service industries now attract the best young employees. "All that my parents wanted was for us to earn £20 per week and, frankly, work for a bank. That was seen as secure."

According to a report published by Rhys tomorrow, the UK would do well to follow the example of the Nissan car plant in Sunderland, which churned out 423,000 vehicles last year.

However, Rhys argues that boosting manufacturing intake from universities and schools will require an overhaul of salary levels to reflect the economic value of engineers, with Germany the main example to follow. "In Germany, engineers are top of the pile," he said.

Aerospace company Airbus is among the manufacturers warning of a shortfall in engineering talent that is hampering all of Europe. The French, German and Spanish-owned maker of the A380 superjumbo manufactures its wings in Broughton, Wales, in a state-of-the-art facility. However, the company has warned that the UK and western Europe are suffering from a shortage of aerospace engineers.

Thierry Baril, head of human resources at Airbus, has warned of a significant shortfall of engineers across the continent. Speaking to the Guardian this month he said that the European aerospace industry needed 12,000 new engineers per year but that educational institutions are producing only 9,000.

He said: "In the UK you have exactly the same problem. Many companies are fighting for the same talent."