The otaku is the scourge of contemporary Japanese youth culture. The term, popularised in the west by science fiction author William Gibson, describes a "passionate obsessive, the information age's embodiment of the connoisseur, more concerned with the accumulation of data than of objects".

Preferring to interact with computers than one another, otaku spend their time in their bedrooms, fuelled by a steady supply of junk food and information, doing things in online networks that are incomprehensible to anyone outside the community.

For the most part, these techno-dropouts cause no real harm. However, the otaku do become a problem when one of their number hacks into a high-profile database. Suddenly the quiet kid next door is thrust into the spotlight, along with geeks around the globe.

Otaku and their western counterparts have existed as long as computers have been networked. The internet has always held temptations for people with the time, the skills and the inclination to seek out its unsecured treasures. It's fun – and occasionally profitable – to try to break into systems.

But collectives of hackers are now gaining attention. Groups like Anonymous or LulzSec exploit celebrated qualities of the technology: it connects people with similar interests, allows them to share information freely and it is the world's greatest collection of archived materials, including detailed instructions for performing denial of service (DDoS) attacks. Although there is a small subset of women involved in their activities, most of the people in these communities are men.

Arguably, there is a gender bias is built into internet and web technology. Each new iteration of computer code is built upon a previous one and, historically, programming has spoken to a binary logic associated with male cognition patterns. Had there been more women contributing to the first computer languages, there might be more female hackers now.

Hacking incidents also carry cultural indicators. According to Aleks Gostev, the chief security expert on the global research and analysis team at the anti-virus software developer Kaspersky Labs, attacks that conscript a network of computers tend to come out of Russia, whereas malware tends to come from India. Gendered attacks might also have different qualities.

Although some of the recent high-profile attacks have political agendas, those examining hacker culture say that most of the people who perpetrate these attacks are in it "for the lols". The researcher Danah Boyd, who has spent the past decade studying online youth subcultures, believes that the motivation of people involved in contemporary otaku and hacker communities is to hijack the attention economy. "I grew up in a hacking culture, but my cohort was about breaking into the so-called secure government and enterprise systems to prove that we could," she says. "Now, there's another kind of subculture. There are still security breakers, but most of it is about capturing a moment that challenges what everyone is paying attention to."

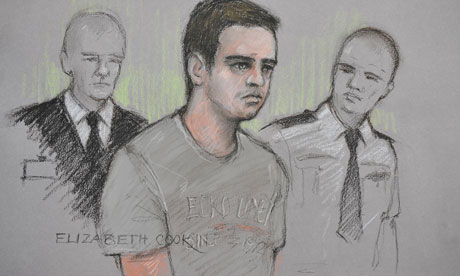

Indeed, there is a "look at me" element to the attacks that Ryan Cleary was alleged to have perpetrated. The apparently growing phenomenon of young people disappearing into their bedrooms to wage war on the establishment may simply be the computer generation's way of getting attention. The harm, ultimately, comes to the systems whose shortcomings are exposed by the quiet otaku next door.