My father never talked about the war. Only now, some 30 years after his death, have I found out what he went through on the western front in 1918, and discovered how deeply it affected his personality. This was one of many surprises when I decided recently to research his life and career as an actor. I was startled to find a very different person from the one I remembered, a discovery that has altered my view of him, and also left me with certain regrets.

He was 43 when I was born, a passive presence about the home, very much dominated by my strong-willed mother, his third wife. He was amiable and kind, inspiring affection, but he was also lazy and weak, and emotionally reserved. He seemed to have no opinions, and was quite hopeless at disciplining me or my younger brother, Stephen. Nor did he offer us any guidance or fatherly wisdom. One abiding memory is of him doing the crossword puzzle, checking the racing form or football results, while he waited for his agent to ring. His refusal to seek work more actively, and generally promote himself, infuriated my mother, and was one of the main causes of their many rows and their eventual separation.

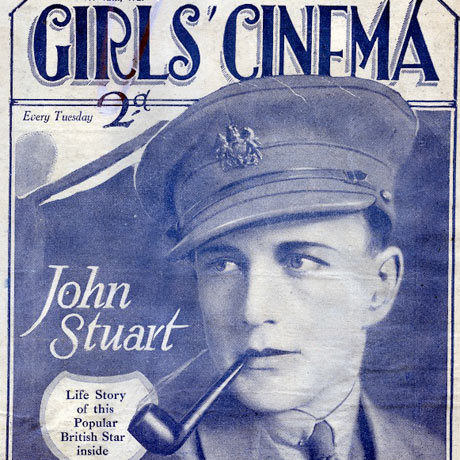

I did know that in his youth in the 1920s, under the name of John Stuart, he had achieved considerable fame as a star of the silent films. Dubbed a matinee idol, he was once thought the equal of Ivor Novello in charm and good looks, and had his own fan club. But unlike the hero of the magical new silent film The Artist – and indeed many of the real stars of the period whose careers were brutally cut short by the coming of sound in 1929 – he survived into the "talkies", and went on to enjoy a lengthy career, notching up 168 films.

My main resource in researching his life was a set of bulky scrapbooks covering his early screen career. After his death I had only glanced at them casually, but now I studied them in detail. They proved a marvellously comprehensive collection of press cuttings: film reviews, interviews and profiles, gossip columns in which he featured, and articles about being a star that he wrote for magazine and newspapers. I was astonished at the contrast between the father I remembered, and the active, ambitious, hard-working young man emerging from these yellowing pages. Could they be the same person?

My first surprise was to find him described as a keen, all-round sportsman. The only sport I connected him with was bowls, yet in the cuttings his athletic abilities were frequently stressed: he had been captain of the school rugby team; he was "a keen footballer who plays for one of the best-known amateur teams in London"; along with Alfred Hitchcock and other film celebrities "he was a founder member of the Kinema Club cricket team"; he was also judged to be a "fine tennis player" and "an excellent exponent" in fencing. All this was news to me and led me to wonder why, despite having two keen sporting sons, he never talked to us of these exploits. Even more unexpectedly, it transpired that he "rode to hounds", an image I found hard to square with his gentle persona, and his portrayal elsewhere as an animal lover.

I was equally taken aback by the physical daring he often had to show. Called on to fight, fence, swim, drive a racing car, and fly in a two-seater plane at 3,500m, he rarely used a double, sustained several injuries, and came close to drowning during filming in Cardigan Bay. The dynamism he displayed in such action, and in pursuing his career generally, seemed to have vanished by the time my brother and I came into his life. And in several articles I found the man I thought had no opinions holding forth in an impressively articulate and forceful way – about the problems of the fledgling film industry, the demands of stardom, the lure of Hollywood, the technique of film acting, and much else.

What, I wondered, had happened to make him such a different person in middle age? Had the failure of all three of his marriages coloured his outlook on life, affected his confidence, and taken him further into himself? These questions came welling up as I probed further into his life as a star, and came across other surprises – that he collected antique furniture, wrote songs and sang on concert platforms.

But the most revealing and moving discovery came in an interview he gave in 1929, in which he talked of his war experience. I knew that as a Scot he had enlisted in the Black Watch at 19, had gone to France and was eventually released from duty with "trench fever". But that was all. After "hours of coaxing and several gallons of China tea", the journalist Nerina Shute eventually got him to open up. "For a kid of that age, war is hell," he says.

When she presses further, he reveals that the young men who went to the front with him, his greatest friends, were all killed. "He admitted that never in his life had anything hurt him so much as the death of these youthful comrades. He never spoke of the things he had seen. Instead of that he built a wall of stone round his private emotions, a wall that has grown, it seems, with the passing of the years."

This confession was an eye-opener. Here, perhaps, was the clue to that reserve he displayed in later years. But perhaps it also explained his worrying tendency to shout out in his sleep. Was he reliving those horrific months in the trenches, recalling his life as a young soldier in France? How I wish I had tried to get him to talk about those traumatic times. Maybe it would have made for a more positive relationship between us and perhaps released some of his demons. For the first time I felt a real sadness that I had not made any decent connection with him during his lifetime.

At least I have one compensation: owning many of his films allows me to bring him briefly back to life at the push of a button.

• Jonathan Croall is writing a book about the screen idols of the 1920s, including John Stuart