Does Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm mean that Star Wars has sold out? Can the Star Wars franchise retain its soul now it has been absorbed into a corporate conglomerate? It’s hard to believe that these questions are seriously being posed. Star Wars was a sell-out from the start, and that is just about the only remarkable thing about this depressingly mediocre franchise.

The arrival of Star Wars signalled the full absorption of the former counterculture into a new mainstream. Like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas was a peer of directors such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, who had produced some of the great American films of the 1970s. Lucas’s own earlier films included the dystopian curio THX 1138. But Lucas’s most famous film was a herald of a coming situation in which mainstream US cinema would become increasingly bland, and it would become impossible to imagine films of the quality of The Godfather movies or Taxi Driver ever being made again.

According to Walter Murch, the editor of Apocalypse Now, Lucas had wanted to make Apocalypse Now but had been persuaded it was too controversial, so he decided to “put the essence of the story in outer space and make it in a galaxy long ago and far, far away”. Star Wars was Lucas’s “transubstantiated version of Apocalypse Now. The rebel group were the North Vietnamese, and the Empire was the US.” Of course, by the time the film was ideologically exploited by Ronald Reagan, everything had been inverted: now it was the US who were the plucky rebels, standing up to the “evil empire“ of the Soviets.

In terms of the film itself, there was nothing much very new about Star Wars. Star Wars was a trailblazer for the kind of monumentalist pastiche which has become standard in a homogeneous Hollywood blockbuster culture that, perhaps more than any other film, Star Wars played a role in inventing. The theorist Fredric Jameson cited Star Wars an example of the postmodern nostalgia film: it was a revival of “the Saturday afternoon serial of the Buck Rogers type”, which the young could experience as if it was new, while an older audience could satisfy their desire to relive forms familiar from their own youth. All that Star Wars added to the formula was a certain spectacle – the spectacle of technology, via then state-of-the-art special effects and of course the spectacle of its own success, which became part of the experience of the film.

While the emphasis on effects became a catastrophe for science fiction, it was a relief for the capitalist culture of which Star Wars became a symbol. Late capitalism can’t produce many new ideas any more, but it can reliably deliver technological upgrades. But Star Wars didn’t really belong to the science fiction genre any way. JG Ballard acidly referred to it as “hobbits in space”, and, just as Star Wars nodded back to Tolkien’s manichean pantomime, so it paved the way for the epic tedium of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings adaptations.

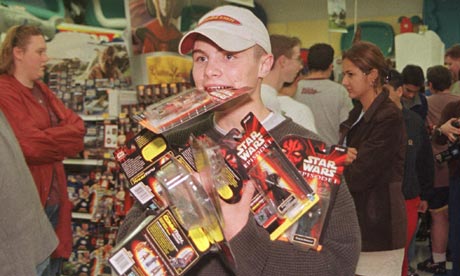

What Star Wars did invent was a new kind of commodity. What was being sold was not a particular film, but a whole world, a fictional system which could be added to forever (via sequels, prequels, novels, and any number of other tie-ins). Writers such as Tolkien and HP Lovecraft had invented such universes, but the Star Wars franchise was the first to self-consciously commodify an invented world on a mass commercial scale.

The films became thresholds into the Star Wars universe, which was soon defined as much by the merchandising surrounding the movies as by the films themselves. The success of the toys took even those involved with the film by surprise. The then small company, Kenner, purchased the rights for the Star Wars action figures in late 1976, a few months ahead of the film’s theatre release in summer 1977. Unanticipated and unprecedented demand soon outstripped supply, and parents and children could not find the action figures in toy shops until Christmas 1977. This all seems rather quaint now, at a time when the merchandising surrounding blockbuster films is synchronised with a military level of organisation, and augmented by a battery of advertising and PR hype. But it was the Star Wars phenomenon which gave us the first taste of this kind of film tie-in commodity super-saturation.

This is why it’s ridiculous to ask if Star Wars sold out. It was Star Wars which taught us what selling out really means.