The community of SF writers has reason to dislike digital copying, or "piracy" as it's commonly labelled in the tabloid press. Genre writers exist, by and large, in the publishing mid-list, where mediocre sales might seem most easily eroded by the spectre of illegitimate downloads. SF, fantasy and horror are also the literature of choice for the culture of geeks most likely to share their favourite authors' works on torrent sites. Not surprising, then, that many professional genre writers and editors respond to the growing reality of copying with the absolutist position that piracy is theft, and should be punished as such under the law.

But SF writers are far from united in that position. Novelist, blogger and digital rights activist Cory Doctorow is well known for providing free digital copies of all his books as a marketing strategy, arguing that in a digital economy, obscurity is a far greater threat than piracy. Charlie Stross blogged such an effective argument against digital rights management on ebooks that it influenced at least one publishing imprint to drop DRM on its novels. And interviewed on the subject in 2011, Neil Gaiman, ever the gentleman, kindly points out that if you are a writer courting fans, screaming "THIEF!" at them and threatening legal action for copying might be … counterproductive.

Of course the easy response is that Doctorow, Stross and Gaiman are all successful writers who can afford to hold such opinions. But like most easy responses, it misses the fundamentals of the argument. Successful writers understand the marketplace they are working within, and they understand that digital copying and file-sharing, like all disruptive changes wrought by technology, create as many opportunities as problems. The digital economy operates on the model of the long tail, and copying is part of how a book or any digital creation moves up the tail. Copying and file-sharing are the internet's word of mouth – and as all good booksellers know, it's word of mouth that really sells books.

It's at the confluence of file-sharing and self-publishing that a new kind of "artisan author" is emerging. In his guide to self-publishing, Guy Kawasaki with co-author Shawn Welch coins the term APE: Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur. Kawasaki argues that by fulfilling all three roles, writers open tremendous new creative opportunities for their work that major publishers are too slow and cumbersome to meet. Self-published writer Huw Howey, whose collection of SF novellas, Wool, became an ebook bestseller before it was published by Century and the film rights bought by Ridley Scott, says that he and the pirates "are tight"; he loves his readers, "even the ones with eye patches". For a self-published author like Howey, downloads from torrent sites aren't a sale lost but a reader gained, the sites themselves not dens of piracy but places where people who are fans of cool stuff go looking for new cool stuff to be fans of. For the artisan author, self-publishing is a preference and file-sharing is an opportunity.

Creative control is the lure for the artisan author. Want to hand-make limited editions of your book and sell them on Etsy? You can. Want to find a kick-ass illustrator on deviantART to make your cover? You can. Want to set up a Kickstarter to fund the next volume of your epic fantasy saga? You can. Want to make a marketing deal with a sponsor who likes you brand? You can. Want to put copies of your book on Pirate Bay to find new readers? You can. The options open to artisan authors are huge, and the potential for creativity truly exciting. In the past, writers have relied on publishers to make these creative decisions for them, but the changes in digital publishing mean that many writers are not just creatively but financially better off either going it alone or negotiating new kinds of relationships with publishers.

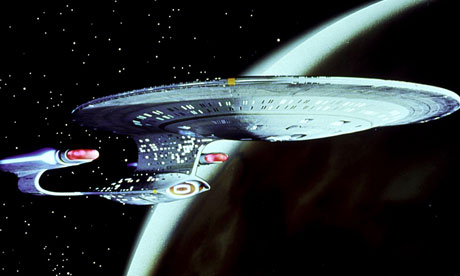

If the rise of the ebook and the growth of file-sharing are a huge meteorite careening towards Planet Publishing, then the artisan authors are gambling on being the fast, adaptable mammals who will crawl out from the rubble of Random House and feast like cannibals on the dismembered careers of dying mid-list writers and their editors. If the artisan authors are right, then file-sharing is the least of the problems traditional authors face. They are tied to a publishing eco-system that may simply be too big and too slow to adapt to the extinction-level event of digital technology.