Bruce Dern was the wayward dreamer of American movies, wild and restless, not built to last. He took a fatal bullet in The King of Marvin Gardens, laid down his life in Silent Running and swam into oblivion at the end of Coming Home. Dern played heroes and villains alike. But he was invariably geared towards the bittersweet send-off or the gaudy comeuppance. To all intents and purposes, he never got out of the 70s alive.

Now, incredibly, the man is back with his best role in decades, possibly his best one ever. The Alexander Payne drama Nebraska casts him as another hopeless dreamer, destined for the rocks, but the performance itself marks a redemption of sorts. At the Cannes film festival, where Nebraska screens in competition, Dern receives both a standing ovation and the best actor prize. He comes staggering into the limelight like a dilapidated Cinderella.

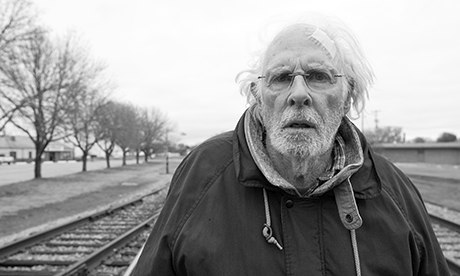

The day after the premiere, the distributors install him behind a wooden screen in a hotel ballroom and have the reporters line up for a private audience. Dern greets each new arrival with an old-school courtliness that contains a top note of chaos. He wants to know where the reporters were born, what outlet they work for, what team they support. At the age of 77, he still possesses the same wolfish charm, the same disconcerting blue stare, the same ripcord voice that we remember from his glory days, when he locked horns with Jack Nicholson or held court with Alfred Hitchcock. But his face is now weathered and his white hair is a blizzard.

"Where are you from?" Dern asks.

London, I tell him. By way of the West Country, in the vicinity of Bristol.

"Ah," he purrs. "Is that below Lyme Regis?"

No, I tell him. Isn't Lyme Regis on the south coast?

"Is it a lot below Lyme Regis?" he says. "Is it quite near Southend?" His compass is scrambled. His sat-nav plays tricks. Already, I fear, we are both out at sea.

In Nebraska, Dern plays Woody Grant, a blasted bit of human flotsam, blowing through a monochrome heartland. Mount Rushmore, he thinks, is just a pile of rocks. The old family homestead registers merely as "old wood and some weeds", while Main Street is a strip of peeling storefronts and home-loan hoardings. Woody thinks he's won a million on the sweepstakes and is on his way to claim his prize. But he's winding down and phasing out. His American dream is almost certainly false.

It used to be that directors treated Dern like some exotic spice; an unruly ingredient to whip up the action. Woody, however, is more absence than presence. He is clenched and withdrawn, only talking when he has to. The role is so far out of the actor's comfort zone, it must have been a devil to play.

"In the movie, you mean?" asks Dern, as though this distinction is crucial. "Well, yeah, that's Woody. He wouldn't do too good in psychoanalysis, because he doesn't know what's inside, it would take two years to get anything out of him. On top of that he's got a couple of banks of lights out and he doesn't hear too well. He's kind of crippled and fucked up. But he knows two things. He wants people to tell it like it is. And he wants to be treated fairly."

He glances up. "Who's that cunt at the table?" he says.

I'm completely at a loss. At what table? At this table? But Dern shakes his head; he's still thinking of the movie. "No, no, the lady," he says. "With the white hair. They're sitting at the table and she says, 'Are you still working, Woody?' And he says no. That's very revealing. He'd like to be working but he can't any more."

Given the grit and tenor of Dern's on-screen image, I always assumed he was from the wrong side of the tracks. In fact he was the rebellious black sheep of a blue-blooded brood. His father was an attorney, his grandfather served as secretary of war and Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson were regular guests at the Dern family pile. He would later mine this gilded pedigree for his brilliant turn as Tom Buchanan, the boorish, old money prince in Jack Clayton's 1974 version of The Great Gatsby.

Back then, Dern briefly rivalled his friend Jack Nicholson as the most vibrant and exciting actor in American cinema. He played circus barkers, conmen and eco warriors. He shot John Wayne in the back at the end of The Cowboys and bagged an Oscar nomination as a Vietnam vet in the acclaimed Coming Home. But where Nicholson went on to fame and fortune, Dern found himself stuck playing "second banana" and was increasingly installed as a wild-eyed crazy, on hand to blow up the Super Bowl (Black Sunday) or abduct sexy models (Tattoo). He had a seat at the table but subsisted on scraps.

He recalls working with Hitchcock, who loved him because he worked hard, came cheap and had a little whiff of danger. The director employed Dern on a regular basis on his long-running TV series and cast him in a pivotal role as a predatory sailor in Marnie. "If I ever said that actors are cattle," Hitchcock once remarked, "then Bruce is the golden calf." Dern grins at the memory. Hitch, he says, was smart and funny and took no nonsense from anyone. "You think he was small," he tells me. "But he was big. Six-foot-one. Weighed 285. He was no one to fuck with."

In 1976 Hitchcock made what would be his final film, Family Plot, with Dern in the lead. It has been suggested that the director was in such poor health that Dern wound up calling most of the shots – although he swears up and down that this was never the case. "Hitch was there every day at nine in the morning and he stayed until seven. At the end of the first day he wanted a word with the crew. We were both there on the soundstage. He was sitting in a little director's chair and I would sit next to him, every day, for 11 weeks, because I wasn't going to miss the opportunity. And he let me. He liked me. So anyway, he stands up to speak to the crew and he's so girthy that the chair went with him. He stands up and the legs of the chair are sticking out parallel to the ground. He doesn't turn. He just says, 'A hand please, Bruce.' So I grabbed the legs and we walks away, like pulling a cork out of the bottle." Dern chuckles, then gathers his thoughts. "And then," he says. "And then he walks around and shakes hands and thanks every crew member by their first name. By their first name! On the first day! Now how about that?"

In the dying moments of our conversation, he beats back to the subject of England; of Southend and Lyme Regis and a blue-remembered holiday to the Lake District, when he ran a race against a shepherd. He will not be stopped; he's in full spate. He's nothing like Woody; he's all curve balls and colour. He escorts me back across the ballroom, towards the wooden screen, explaining at length how he has always loved running and was good at it too, and yet Jiminy Cricket, how fast was that shepherd? "We ran a race around a bunch of pastures for about 50 miles. And it took me about seven hours and a half. It took him six hours 15. And he had the world record and then won the Comrades' medal twice. And wait a fucking minute! He was just a sheep herder!"

The next journalist hovers eagerly beside the screen, all prepped for his interview. Dern ignores him. He shakes my hand and peers into my face.

"And I was always amazed. I said, 'Where do you live? Where's the town that you live?' And he said, 'Oh, I just live around here, mate.' Is that true?" he asks, frowning. "Do they really?"

I don't know. I can't say. The reporter is waiting. Do they really do what? "Just live in the fields," says Dern. And with that he turns, mid-flow, to greet the new arrival. "Now how about that?" he marvels. "He was just a fucking sheep herder."

Nebraska is on release in the US, out in the UK on 6 December and Australia on 28 December

• Show us your family road trip photos

• Read an interview with Alexander Payne

• Watch an interview with Dern and Payne from Cannes

• Oscar predictions 2014: Nebraska

• Watch Xan Brooks review the movie and read Peter Bradshaw's first take from Cannes

• Watch out for a special Nebraska supplement in this Sunday's Observer