From the Arab revolutions to indigenous-led campaigns and, more recently, the spontaneous social movements that burst in Turkey and Brazil over the last three years, the internet seems to have turned into a megaphone for social movements.

The networked nature of web 2.0 applications, in particular social media, and the explosion of users worldwide provide citizens and activists with unprecedented tools to communicate their ideas, mobilise supporters and take action outside established hierarchical power structures. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have become privileged fields of action for professional campaigners as well as grassroots movements.

With their built-in feature allowing many-to-many communication, social media have revolutionised the way information is produced and shared: everyone is encouraged to participate, share opinions, pictures and videos on issues they care about or witness and instantly upload them from their smartphone on the Internet. Institutions and individuals that represent public authority are now under constant citizen scrutiny.

They know that any abuse, any mistake can spark online retaliation and take proportions that may be hard to control. Many activists and academics see in digital networks a new source of power that will eventually force the ruling elite around the world to become more transparent, more accountable and protect human rights and democracy.

Unfortunately, there is no such thing as a technological fix to a complex problem and, the solution itself has quite a few downsides. Indeed, while digital technologies have helped the success of social and revolutionary movements, they also tremendously enhance the effectiveness of state surveillance.

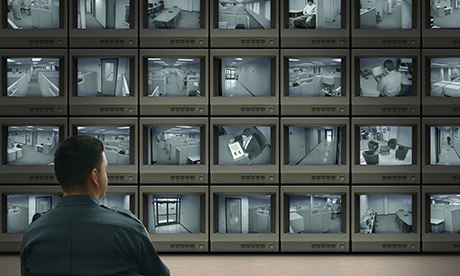

Due to the supervision they exert on the physical infrastructure, governments are tempted to use digital networks to control populations by monitoring communications, blocking access of certain users or even tracking and imprisoning dissidents, e.g. in China and Iran.

Recent revelations by the Guardian on the surveillance system set up by the US National Security Agency (NSA) and its British counterpart: the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) have shown that this is not an exclusive feature of authoritarian or non-democratic regimes.

The surveillance system deployed by these two western powers uses every single means at hand, from tapping online communications and phone calls, to extorting user data from private companies such as Google, Apple and Microsoft, and to archiving billions of bits of personal information into secret data centres, all in the name of security.

Let's be clear on one thing: it is still preferable to be a political dissident in the USA than it is to be in a country like China. But the level of surveillance achieved by democratic governments, in clear violation of their own constitutional provisions, privacy rules and without public debate is a matter of real concern. Similarly, the pressure exerted against whistleblowers and journalists who stand up against it, is unsettling. Admittedly, these practices seem more characteristic of those of Beijing or Tehran than those of Washington, DC or London.

It would be wrong to assume that digital technologies have some kind of built-in effect that will necessarily result in a more transparent and democratic society. History tells us that such assumptions are inaccurate; technologies are only as good as the use we make of them. As citizens and activists, we must recognise this and act accordingly. Good practices include:

• Know what you publicise. There are no secrets on the internet. All digital information is accessible for those who really want it.

• Educate yourself. Some organisations such as Mozilla, the Electronic Frontier Foundation or the Tactical Technology Collective are working hard to keep the Internet open and secure for ordinary citizens and human rights activists. They provide a lot of tools and information on how the Internet technology works and what it entails for our freedoms.

• Encrypt, encrypt, encrypt. Get used to GPG software to encrypt and sign your data and communications.

• Support anonymity and privacy online. Install the Onion Router for surfing the web and prefer search engines that protect your privacy, e.g. Duck Duck Go.

• Be critical of official information channels and mainstream media when they try to justify the maintenance of uncontrolled state surveillance to protect us from criminal behaviour.

Creeping surveillance is not solely a threat to privacy; it has consequences on human dignity, freedom of expression and information and freedom of association. For these reasons, state surveillance practices need to be framed by the adoption of a regulatory framework that is flexible enough to respond to a fast-evolving sector and strong enough to keep us secure from abuses.

Over the past year, 300 organisations have come together to support the International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communication Surveillance. Today, citizens and activists have an opportunity to join this global movement by endorsing the Necessary and Proportionate Principles, and stand for the protection of human rights in the information society. What are we waiting for?

Geraud de Ville is a PhD researcher on on indigenous issues, ICTs and development at The Open University. Follow @gerauddv on Twitter

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. To get more articles like this direct to your inbox, sign up free to become a member of the Global Development Professionals Network