On a bright Tuesday afternoon at around 3.15pm, a handful of plain-clothed FBI agents climbed the stone stairs of Glen Park Library, an unobtrusive building on Diamond Street in San Francisco. They entered the library in staggered succession, gradually making their way towards its far corner: the science fiction section. There, sitting at one of the faux-wooden tables, was a pale young man with dark hair, jeans and T-shirt. He was on his laptop, chatting with someone online. Staff had not recognised the slim man with wide-set eyes, but then people often came here to use the free public Wi-Fi. Once they opened their laptops they would see a window pop up, offering unfiltered content on the condition they avoided browsing illegal content "out of respect" for fellow library users. It seems the young man wasn't complying.

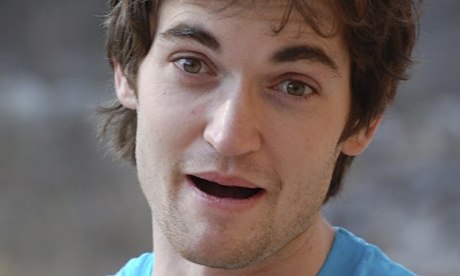

His name was Ross Ulbricht, a 29-year-old former physics and engineering student from Austin, Texas. Many men of his background were in this same city to launch a technology startup or two, but the FBI believed Ulbricht was into something far darker: manning a vast, black market for online drugs and other illegal goods known as Silk Road. He was, they believed, a millionaire drugs kingpin who had twice ordered someone killed to protect his empire.

There was a crash that sounded like someone had fallen onto the hard, tiled floor, library staff later remembered. Poking their heads around the shelves, they found the young Ulbricht pressed up against the window by what seemed to be several other library patrons. It looked like a fight, at first.

"We're the FBI," his assailants said, adding that everything was under control. Soon Ulbricht was in handcuffs, and chatting to several agents who blockaded him into a corner of the library, according to another witness who posted her account online. The agents walked him out of the library, two of them returning not long after in blue FBI jackets to do a sweep of the area where Ulbricht had been sitting. They found nothing. The person Ulbricht had been chatting to online, according to an FBI complaint, had been a cooperating witness in their investigation.

This was the result of more than a year of dogged cyber sleuthing and old-fashioned detective work, and news of the arrest broke the following day, 2 October 2013. Police claimed that Ulbricht had been running Silk Road since 2011, and for the last year had done so from his home in San Francisco as well as a nearby cafe. He had operated under the name Dread Pirate Roberts, a character in the film The Princess Bride that referred to a mythical persona shared between several people. They charged him with drugs trafficking, money laundering and attempted murder.

The FBI agent who led the team investigating Ulbricht, Christopher Tarbell, had also been responsible for the 2011 sting in New York on Hector "Sabu" Monsegur, leader of the notorious LulzSec hacker group.

"He's a very big deal," says one lawyer who has dealt indirectly with Tarbell.

"He does most, if not all of these cases," said another source with knowledge of the investigation.

By Thursday the FBI had shut down Silk Road. Anyone who attempted to access the site saw a large digital poster saying it had been seized by authorities. Police also took possession of a digital wallet allegedly belonging to Ulbricht containing thousands of Bitcoins, the anonymous, crypto-currency used throughout the Silk Road market. To date it is reportedly worth $34.5m, and it's thought that more of the Dread Pirate's takings are still at large online. They claimed Ulbricht was making $20,000 a day on sales commissions, amassing a total of $80m, much of which was reportedly going back into maintaining Silk Road operations.

The whole Silk Road enterprise had reportedly seen $1.2bn in sales in its existence, and nearly one million anonymous customers, making it perhaps the world's biggest online marketplace for drugs.

Chillingly, the FBI indictments also claimed Ulbricht had ordered two hits against people whom he thought might expose his clients, one against an "employee" of Silk Road in January 2013 and then against someone, who was in fact an undercover agent, threatening to leak names of his clientele. In the first hit, police say Ulbricht offered $40,000 for the job, and asked for "proof of death" in the form of a video. Police staged photos of the death, and when Ulbricht saw them stated that he was "a little disturbed, but I'm OK". "I'm new to this kind of thing, is all," he added. "I don't think I've done the wrong thing."

After the arrest, photos of Ulbricht's smiling face were soon scraped from his profiles on Facebook and LinkedIn, and posted on hundreds of websites, blogs and Twitter. On Thursday morning, another young San Francisco resident picked up a copy of the Examiner newspaper and was startled to see Ulbricht on the front page. He took a photo with his phone and texted it to his housemate. "Funny," he said. "Looks kinda like our sub-letter."

"Not looks like," his friend replied. "Is." He sent back a link to a news article, and the descriptions of a Texas University physics grad who had worked as a "foreign currency trader."

"Holy shit."

The two men, who named themselves only as Drew and Brandon in an interview with Forbes, had been living in the house where Ulbricht was renting a room for $1,200 a month on 15th Avenue, in San Francisco's West Portal suburb. They explained that Ulbricht had applied for a room on Craigslist, identifying himself as "Josh", a Texas man who was "good-natured and clean/tidy." He had no mobile phone and chose to pay in cash. The housemates weren't suspicious because "Josh" had just moved from Sydney, Australia.

Brandon ended up living with Ulbricht for two months and said the man "seemed like a normal guy". He was friendly and polite, had few possessions – primarily his laptop and a few changes of clothes – and spent most of his time in the master bedroom, on his computer, engaging in what he claimed was currency trading. The one oddity they noticed: "Josh" liked to walk around without a shirt. He reportedly almost never went out, spending America's 4th of July holiday at home, and cooking steak dinners for one. For all the money he allegedly made, Ulbricht seemed to have spent very little of it at all.

Ulbricht had family back in Austin, but housemates said he had cut off ties with friends. His grandmother, when she first heard about his arrest, seemed nonplussed by the whole affair. She told Forbes that Ulbricht was "good with computers". His half-brother, Travis, called him "an exceptionally bright and smart kid". A close friend and former housemate, Rene Pinnell, told the Verge that police had messed up. "I'm sure it's not him."

No one close to Ulbricht seemed to believe the low-key, young scientist was the notorious "pirate" behind Silk Road.

Ulbricht's alleged, dreamlike world as the internet's Dread Pirate Roberts would have been the antithesis of the real world around him. Drug dealing was nothing new in San Francisco.

A few miles north of West Portal, in front of the larger San Francisco Public Library, more than a dozen of the city's homeless are wandering a grassy square or lying like planks under thin blankets. In broad daylight and directly in front of the library, a homeless man in a wheelchair hands a pair of $20 bills to another, receiving a small package in exchange. "See you later, asshole," the drug dealer says smirking, as his customer secrets the package into a thick, yellow coat.

Such transactions are commonplace in San Francisco and the Silk Road was meant to be their alternative: a place where anyone who wanted drugs could buy them without associating with underhanded dealers or entering dangerous alleyways.

In the US where laws over the use of cannabis or possession of class-A drugs can be wildly different between states, it also made it easier to hide from the law. And buying drugs from a real-world dealer meant you could never be sure if the product was good quality.

On the Silk Road, you could get anything from "red joker ecstasy pills" to LSD and check the reviews and star-ratings of each dealer left by previous customers, as you might on eBay or Amazon. There were 10,000 products for sale in the spring of 2013, 70% of which were drugs. But there were also 159 listings for "services," most of which were for hacking into social network accounts like Twitter or Facebook, and more than 800 listings for digital goods such as pirated content, or hacked Amazon and Netflix accounts, according to the FBI indictment. Fake drivers' licences, fake passports, fake utility bills and fake credit card statements.

Everything was here, facilitated by the Silk Road.

Customers felt safe because they accessed the site via Tor, an anonymising network that up until recently was a reliable way to mask their tracks, even from the police. You never paid with credit cards or PayPal on Silk Road. The only acceptable currency was Bitcoin, an encrypted digital currency that couldn't be traced, with no government or bank behind it. The currency was regulated by a network of computers, and represented by a long string of numbers.

While there are other sites that sell drugs, the Silk Road's user friendly interface and third-party payment system made it more popular than others. Many customers also chimed with the Dread Pirate's libertarian principles, which he wrote about on Silk Road's forums.

In the last two years the Silk Road's Dread Pirate had given a handful of press interviews, unusual given his insistence on staying anonymous. In a 2011 interview with Gawker gaming site Kokatu, he said his views stemmed from the anarcho-libertarian philosophy of agorism. "Stop funding the state with your tax dollars and direct your productive energies into the black market," he said.

Then in 2013 the Dread Pirate told Forbes in an interview that Silk Road's "core" role was "a way to get around regulation from the state". He even hinted that Silk Road might head in the direction of selling weapons. "Firearms and ammunition are becoming more regulated and controlled in many parts of the world," he said.

Ulbricht was a strong libertarian, a member of the Libertarians Group while studying at Penn State University and identified in his school paper as a supporter of US presidential candidate Ron Paul. The one blog post he published on his Facebook profile was titled "Thoughts on Freedom," a philosophical exposition of his libertarian ideas. He posted it on 5 July 2010, just after America's Independence Day; exactly three years before he would be holed up indoors in San Francisco.

In one way, Ulbricht's alleged work chimed with a prevailing belief among technologists in Silicon Valley that the right algorithm, the right software, can spark social change. It is hard to walk down a street in California's Bay Area without passing a startup founder who claims he or she can fix the American health system, or education, or use a GPS location tracking to predict crime, with some sort of app. Companies such as Airbnb have completely upended industries and their founders, like Ulbricht, are hackers at heart. They subvert not just lines of software code but entire systems of thought and economic structure. Ulbricht was taking this and the internet's anti-hierarchical tendencies further, embracing the libertarian notion that private morality was not the state's affairs, particularly in the case of activities such as drug use or prostitution.

Many observers were shocked at the news that Ulbricht had chosen to live and operate in San Francisco when he could have been hiding out in Iceland or Latin America, and that he had given lengthy interviews to journalists. "When you start giving interviews like the CEO of an established company, it's just wrong," says Pavel Durov, another 29-year-old technologist who recently visited San Francisco and had been following the story of the Dread Pirate.

Speaking over a cup of camomile tea at a five-star hotel on Market Street, Durov is the successful head of another, rather more legal online network, called VK.com. Called the Facebook of Russia, VK gets more than 50 million monthly users, and as any successful businessman in St Petersburg might, Durov has had his own brushes with the Russian law. Such experiences have helped reinforce his own strong libertarian views. "I believe the role of the government is too big," he says. "Society must be more decentralised."

But Durov also doesn't care for the Dread Pirate's apparent thirst for notoriety. "If you're involved in something like that and everybody ignores you, the officials ignore you and you ignore the officials, it's OK. It's like you don't exist."

Ulbricht seems to have cared more about making an impact than in maintaining complete anonymity. He reportedly took pains to keep himself anonymous, going online through Tor and only communicating through the Silk Road chat system.

"The highest levels of government are hunting me," he told Forbes. "I can't take any chances."

Yet in fact he took plenty of chances. In one of the first postings about Silk Road on other online drugs forums, in January 2011, a commenter said: "Has anyone seen Silk Road yet? It's kind of like an anonymous amazon.com."

The posting linked to the site's Tor address and a blogpost with instructions. The poster, nicknamed, "altoid" deleted their comment, but someone else copied and pasted it onto another forum. Then "altoid" made a careless mistake: he posted on another online forum of Bitcoin users, asking people to contact rossulbricht@gmail.com.

In July, Ulbricht was visited at his home by customs and immigrations officials who had intercepted a package of counterfeit IDs from Canada, all with different names but with photos of Ulbricht's face. The agents didn't arrest him even though, in another bizarre display of recklessness, Ulbricht mentioned that anyone could "hypothetically" go into a website called Silk Road and buy fake ID documents there.

Police carried out further online investigations and discovered six online servers, through which they could observe the buyers and sellers of Silk Road making their Bitcoin transactions. The FBI has said in court papers that it has accessed months' worth of sales history from Silk Road, giving them new information on the site's dealers.

The UK's National Crime Agency says more arrests are on the way. Before they arrested Ulbricht, the FBI had taken one of the Silk Road's top dealers into custody in July – then flipped him. Steve Sadler of Seattle, who was known as "Nod" on Silk Road, reportedly sold heroin, cocaine and crystal meth on the site, but ended up working with agents for several months to help track down their biggest target, the Dread Pirate himself.

Ulbricht has denied his involvement in Silk Road, or that he was ever its administrator, but the prospect of a dragnet operation to bring in other dealers following his arrest will still make any of the nearly 960,000 registered users with the site – 30% of whom were in the US and Brits being the second biggest contingent – very nervous.

Another online drugs bazaar, called Atlantis, shut down in September, while there were reports that Black Market Reloaded, another, would shut down too, although that hasn't happened. Police will probably continue to tighten the noose on more black markets.

"The best way to change a government is to change the minds of the governed," Ulbricht had said on his LinkedIn page, where he described himself as an entrepreneur.

"I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force." The "economic stimulation" came to fruition with Silk Road, but in the end the very hierarchy he seemed to fight against caught up with him, handcuffs in tow.

Parmy Olson is a technology writer for Forbes magazine in San Francisco. She is the author of We Are Anonymous (Little Brown, 2012)