Anyone who has ever snarled on some icy platform as a track clearing machine failed to cope with the wrong kind of snow, or balanced a chair on a table to reach a light bulb with inexorable consequences, knows exactly what "a Heath Robinson contraption" is. The Michelangelo of the ungainly machine was born in 1872, and by 1912 Heath Robinson was in dictionaries – and still is – defined as an absurd and frequently doomed overcomplication to achieve some pathetically simple task.

A group of his admirers is now fundraising for a purpose built museum to celebrate his life and showcase hundreds of his works, including "A simple method of cracking nuts" – a man sitting impassively at his dinner table waiting for all the other furniture in the room to crash from a ceiling pulley on to his walnut: nothing can possibly go wrong.

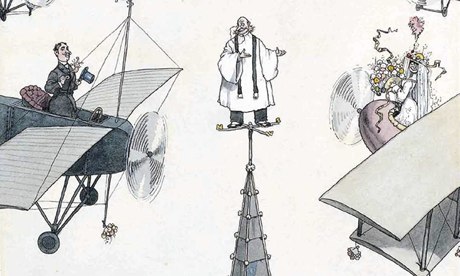

The thrills and torments of modern life often inspired him: he drew a smart young couple embracing precariously from the balconies of their art deco flats, and a vicar teetering on top of a steeple about to marry a pair flying their own separate planes.

He could even crack jokes about the horrors of the first world war: one shows the unleashing of the Germans' latest dastardly weapon – clouds of laughing gas rolling across the trenches. The troops, trapped in a world in which there was very little to laugh about, adored his jokes, and hundreds wrote with suggestions of absurdities they encountered which he could draw. Only the second world war, with his three sons enlisted, defeated him – though one of the prototype computers built by the code breakers of Bletchley Park was named the Heath Robinson in his honour.

Geoffrey Beare, a trustee of the William Heath Robinson Trust charity, and author of several books on his work, describes him as "the essence of a good chap". The collection includes an endearing self-portrait of the artist with his favourite cat, Saturday Morning, named after the time he loved best.

The proposed museum would be a major attraction for Pinner, the north-west London suburb where he lived for many years. The collection of more than 500 original artworks – including the landscape paintings which could not earn him a living, and the book illustrations and cartoons which did – was given by Heath Robinson's son-in-law, in the hope that it would go on permanent public display.

At present there is only space to show a handful of pictures in one small room in a Georgian house restored as a community centre, and also worked on by the trust. The proposed museum, to be designed by architects ZMMA, would have an archive to conserve the entire collection, with a permanent exhibition telling his story – including letters from fans such as HG Wells and Rudyard Kipling, and changing exhibitions of his work. The trust is in the last days of a fundraising drive through Kickstarter, but is still a little short of the target for match funding to secure a Heritage Lottery Fund grant.