The first time I met Hanif Kureishi it was the mid-80s, and we talked about writing fiction for Faber and Faber whose list I was directing. Kureishi came into my office like a rock star and I remember thinking that he did not seem in need of a career move. He was already riding high on the international success of his screenplay, My Beautiful Laundrette.

In fact, Kureishi was cannily pondering his next step. He was on the lookout for a means of self-expression that might sustain a way of life and over which he could have some control. Movies, he said, were chancy, a gold-rush business. There was money in novels and a mood of great expectations as a new generation of writers, especially from the Commonwealth, came through. I had just published Caryl Phillips's first novel, The Final Passage, and Kureishi expressed a quite competitive desire to outdo his Caribbean rival. Four years later, he completed The Buddha of Suburbia in which, as a sly nod to my role in its gestation, I got a walk-on part – as a policeman.

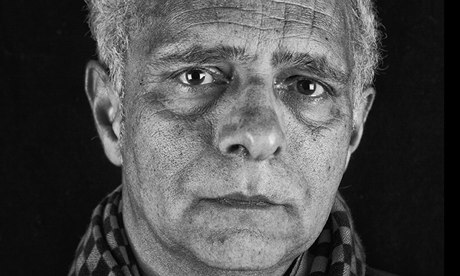

Today, with Kureishi's latest novel, The Last Word, due for publication, it's a good moment to review his record. To the New York Times, he's "a kind of post-colonial Philip Roth"; for the Times, he is one of "50 greatest British writers since 1945". Approaching 60, he has reached the age of honours: a CBE in 2008, plus a characteristic barb ("If it's good enough for Kylie Minogue, it's good enough for Hanif Kureishi"); the PEN/Pinter award in 2010. Like Pinter, he has just sold his manuscripts to the British Library.

Unlike some, he hasn't left for America and still lives in Shepherd's Bush, west London, where he continues to write fiction and screenplays. Le Week-End, directed by Roger Michell, starring Lindsay Duncan and Jim Broadbent, was an acclaimed cinema release in the autumn of 2013. The Last Word comes out on Tuesday. Not many contemporary writers pull off that double, especially after 30 years. But that's the thing about Kureishi: he has always performed in many dimensions (short stories, essays, screenplays), projecting a mischievous air of jeopardy and transgression.

When I visited him at home in west London just before Christmas we began to explore his overlapping lives. From a career of thinking and talking about himself, the public Kureishi has morphed into someone he can happily discuss as a kind of alter ego. In the past, he has said that he gives "at least one interview a week. Over a period of time you work up an account of yourself and one day you find you even believe it. Finally, it has become the story of your life." Exactly so.

You might say that he's been playing a double game since the day he was born in Bromley to an English mother and a Pakistani father on 5 December 1954. As a "child of empire", the young Kureishi grew up in two worlds, western and eastern. Originally from India and later Pakistan, his father's family are what he calls "upper-middle-class". He continues: "My grandfather, an army doctor, was a colonel in the Indian army. Big family. Servants. Tennis court. Cricket. Everything. My father went to the Cathedral school that Salman Rushdie went to. Later, in Pakistan, my family were close to the Bhuttos. My uncle Omar was a newspaper columnist and the manager of the Pakistan cricket team."

After partition in 1947, the Kureishi family went to Pakistan to create a new society, the Islamic state called Pakistan, seeing themselves like American pioneers. "Basically," he says now, "I am a sort of English kid, but I was always linked to the empire. Not only am I the child of a mixed marriage, but I always had that history."

His father, Rafiushan (Shanu), had taken the boat to England to study law. When the money ran out, Shanu landed a desk job at the Pakistani embassy, met his future wife, Audrey (Buss), on a double date and ended up in south London with two children, Hanif and Yasmin, eking out a life of permanent disappointment, writing novels on the kitchen table, but getting turned down. "He had wanted to be a writer and an artist," says his son, introducing a characteristic note of frosty candour into the conversation, "and he hadn't achieved that."

Although his father's fate must have been a dreadful warning, Kureishi looked to literature for self-enlightenment and self-advancement. The first prerequisite for any artist, Kureishi had something to say, and a burning need to say it, reinforced by 50s Bromley. "It was rough down there," he remembers. "The racism of the 50s and 60s that we, unlike France and Germany, have grown out of, was overt. You were made aware of your difference all the time. So you began to think, 'Where does this come from? What does it mean?'"

Kureishi was confused, but singular. He was another kind of pioneer, the first of many "writers of colour" to have been born here. "I was born in Bromley and grew up in the suburbs," he says. "VS Naipaul and Salman Rushdie were born elsewhere. By the age of 14, I'm a Pakistani kid who likes Jimi Hendrix, takes drugs and wants sex. How do you make a book out of this?" He goes on, slightly professorial. "You have to invent a style and a world. It was a new kind of English realism." In the past, Kureishi has admitted "denying my Pakistani self", so this is a new tune. Challenged about this, he retreats to the conundrum of his identity: "I just didn't know what to do with it or what use it could be to me. My dad said, 'You should change your name. You could pass.'"

At home, in Bromley, the family hinterland had no relevance or meaning. Here, he was just "a Paki". Then came Enoch Powell and the "rivers of blood" speech. "It was terrifying," he remembers. "We thought we were going to be sent back. We'd been brought over here to help run the NHS and the public services, but now we realised that we were just Pakis and niggers. There were a lot of skinheads. My dad was persecuted as he came home from work and he thought it was all too difficult. But I liked my name. I couldn't change it to Pete Brown. So what I had to do," he continues, "was uncover who I really was. You saw that a lot in the 70s: blacks, gays, women. It all came out of EP Thompson [author of The Making of the English Working Class)] and the idea that ordinary people have their own history."

But this was not easy. Kureishi's grandfather and uncles were far from ordinary. "They were here all the time," he remembers. "My grandfather, the colonel, was terrifying. A hard-living, hard-drinking gambler. Womanising. Around him it was like The Godfather. They drank and they gossiped. The women would come and go." A version of the young Kureishi's life eventually found its way into both My Beautiful Laundrette and The Buddha of Suburbia. Another rendering of his grandfather recurs in the character of Mamoon Azam, the tyrannical old writer in The Last Word. At the same time, playing that double game, it also becomes a version of Kureishi's literary self.

Books were essential to his assimilation. It was through his life as a writer that he began to discover who he was and to reconcile the warring parts of himself. The doubleness persisted. He would be suburban and metropolitan. Arrogant and shy. An entertainer and a spectator. A bad boy and a good son. A professor and a hooligan. Provocative and complicit. Hankering after the academy, yet living on the street. Juxtaposing high art and popular culture. Quoting Beckett and Kafka, but celebrating Carry On films, reggae and pop music.

Late-70s Britain was on the turn, but the big story, the making of a multicultural society – "the empire strikes back" – was still in progress. Kureishi was just one of several young emerging talents ("Commonwealth writers") who were beginning to find a voice within English society. Then Salman Rushdie and Midnight's Children burst on to the scene in 1980. Kureishi remains competitive with Rushdie. "I wasn't influenced by Midnight's Children," he insists when I bring this up. Really? "No. It came too late. There was no 'magic realism' – no magic only realism – in Bromley. I was influenced by PG Wodehouse and Philip Roth."

He moves the conversation away from Rushdie, to stress his own credentials. "I like to think I'm a comic writer, in the English comic tradition of Waugh and Amis and Angus Wilson." But then, to reinforce his sober literary self-image, he adds: "I would not want just to be funny. It would be really tiresome to have to do that all the time. I like writing the sad bits. There are no sad bits in Wodehouse."

Kureishi's quest for meaning somehow had to make sense of many sad bits, some awkward bits, and the kinds of bits that are foreign to the pages of Wodehouse: politics, pop culture, sex, drugs and race. "How do you make a story out of that?" he challenges. Kureishi's path to a mature coherence was tortuous, a bigger struggle than he wants to let on.

"Of course, any writer has to invent a style that contains them," he remarks, "and find a new way of putting together these things about yourself that are puzzling." Literature, as so often in the past, became the outsider's salvation. "I was reading James Baldwin," he says, "and working out how I fitted in. Being a writer seemed the way to go." As a teenager, already writing novels and plays, he got taken up by the flamboyant publisher Anthony Blond. At first, he wrote pornography under the name of Antonia French. His work has always revelled in characters either searching for, or fleeing from, sexual fulfilment.

Moving towards the mainstream, he wrote plays for the Hampstead theatre and the Soho Poly. By the time he was 18, he was working at the Royal Court – "I'd got out of Bromley quite early" – and meeting a brilliant new theatrical generation that included David Hare, Christopher Hampton, and the director Max Stafford-Clark. "We were very politicised," he says. "We called ourselves black at the Royal Court. Even the women called themselves black." Then, discovering he did not like working in the theatre, because he really wanted to be a novelist, he says he "got stuck. I wasn't going to make a living. It was all going off a bit". Finally – eureka! – Channel 4 asked him to write a film, his lucky break.

The script of My Beautiful Laundrette reached the director Stephen Frears, whom Kureishi describes as "my best mate", adding that "Frears found a style for My Beautiful Laundrette, which was seriously overwritten, which made it comic and theatrical". Kureishi's vision of gay skinheads and Thatcherite Pakistani businessmen and their women was a revelation. My Beautiful Laundrette was nominated for an Oscar and won the New York Critics' best screenplay award.

1985 was Kureishi's year, the moment when the disjointed fragments of life and art fell into place. At last, he had found a way to be funny, edgy, true and original. He had found his place. He was just 31. Reflecting on this moment, Kureishi now speaks in a rather grandiose way that he has probably used often in writing classes (he's a professor of creative writing at Kingston University) and in interviews with foreign journalists. "In the early 1980s," he remarks with that peculiar detachment, as if describing someone other than himself, "it was Midnight's Children and My Beautiful Laundrette that changed things. You really felt that British writing had found a new voice and a new way. It had to. It couldn't go on... there had to be something new."

Inspired by the success of My Beautiful Laundrette and motivated to give the British Pakistanis of his generation a distinctive articulation, Kureishi focused his imagination on fiction. "I had always wanted to be a novelist," he says, speaking with quiet passion of the part played by The Buddha of Suburbia in the making of multicultural Britain.

"If Britain is a cultural force in Europe – which I think it is – then that's because of multiculturalism and diversity," he says. "I'm proud to have seen that happen. Somehow, Bromley in the 50s and 60s did not boil over. It has been an extraordinary revolution when you think how class-ridden and deferential it used to be. Britain became a multicultural society by mistake. No one ever thought, 'How do we make a multicultural society?'"

The Buddha of Suburbia, coming so soon after My Beautiful Laundrette, put Kureishi in a unique position. He was both a popular bestseller and critically acclaimed. He had made those links between Bombay and Bromley, reconciling the one to the other. Within British culture, he was both an icon of multiculturalism and its gadfly, especially to the rising generation of new Britons. Zadie Smith remembers her first reading of The Buddha of Suburbia, aged 15: "There was one copy going round our school like contraband. I read it in one sitting in the playground and missed all my classes. I'd never read a book about anyone remotely like me before."

The public phase of Kureishi's quest for meaning and identity was over. Indeed, it would be Zadie Smith in White Teeth who would make the significant creative advance on to the new ground broken by The Buddha of Suburbia. Kureishi was personally rich ("a little overwhelmed at the number of cheques that turned up at my council flat"), but the well of his imagination was depleted. Or, to put it another way, he had possibly expended so much creative energy in achieving the literary synthesis so dazzlingly displayed in Laundrette and The Buddha of Suburbia that there was no more fuel in his tank. Creatively, he had made a unique statement, based on a profound interrogation of himself. Like many literary pioneers, he could break out of the matrix of his imagination only with the greatest difficulty.

As the 80s became the 90s, Kureishi reached an impasse. His perfect pitch became discordant and uncertain. His second novel, The Black Album (1995), a satirical look at fundamentalism after the fatwa, was less successful. Kureishi found he could no longer hunt with the hounds and run with the hare as he'd liked. "My sense of myself changed," he says. The two events that compromised his role as an enfant terrible who was also a spokesman both occurred in the private arena, with his family.

First, he became the father of twin boys; then his father died. "I found I was shoved into the next zone," he says. "I'd been this kid with long hair, hanging around in London, taking drugs and having sex with girls. Suddenly, I was getting up at seven in the morning and taking my kids to the park. My life switched. I'd become an adult. These kids were looking to me as a father and I was responsible. I could no longer write books from the point of view of a 17-year-old."

It says a lot about Kureishi's investment in that teenage self that it was not until his 40s that the boyish Hanif could make the transition into adulthood. At this point, apropos his new life as a father, he says something that possibly holds the key to the inner man. "That's what's great about being a writer," he remarks, out of the blue. "Every 10 years you become somebody else."

But the somebody else he became during the 90s and into the millennium was not a writer at home in the world. Kureishi was still in search of his identity and role. His muse was still the imp of the perverse. He had exploited that in public. Now, much more controversially, he would attempt it in private. In The Buddha of Suburbia, of course, he had mined his family hinterland. Now, he would get up close and personal.

Possibly he was drawn to the psychodrama of family life, especially as a writer, with Graham Greene's "splinter of ice", who has always been incorrigibly transgressive. After the publication of The Buddha of Suburbia, his sister, Yasmin, had accused him, in the Guardian, of selling the family "down the line" with his portrait of their parents and grandparents. "My father," she says, "felt that Hanif robbed him of his dignity." Father and son did not speak for many months. Today, in Shepherd's Bush, he makes a point of telling me that he "spoke to my mum this morning".

That was as nothing compared with the furore about Intimacy, a novella about a man leaving his wife and two sons, a self-lacerating fiction that some felt to be too shockingly close to home (Kureishi had just left his partner, Tracey Scoffield, and their twin sons). He won't talk about this damaging episode now beyond wryly acknowledging that it "put me in trouble with the chicks".

It was after this crisis that he embarked on a programme of psychotherapy with the analyst and writer Adam Phillips, a twice-weekly relationship he treasures. Inevitably, he must make light of it: "You start to feel better after about 10 years," he says. Therapy has absorbed much of Kureishi's psychic energy. In a recent essay, he describes how far his fiction has come from his Bromley days: "I'm interested in the area where philosophy, literature and psychoanalysis cross over – the mind in the world."

The more Kureishi turned inward, the feebler the creative dividends. His 2008 novel, Something to Tell You, was described by the New York Times as "a sprawling romp". From another point of view, it was notably unedited and artistically unfocused, a casual anthology of trademark themes: kinky sex, metropolitan drugginess and suburban decadence braided with snippets of philosophy and psychotherapy.

His new novel, however, The Last Word, returns him to his personal hinterland. Mamoon Azam is an eminent novelist who has authorised an ambitious younger writer, Harry Johnson, to undertake his biography, in the hope that it will rescue his career and reputation. The idea that the end of a life is as interesting as its beginning is a fruitful one, with echoes of the relationship between VS Naipaul and his biographer Patrick French. But, at heart, it's really a commentary on the complicated inner turmoil of Kureishi's own career.

As usual, the epigrammatic Kureishi has a good line in good lines. There are sharp asides about England, (a "wilderness of monkeys"), and art ("anything good has to be a little pornographic"), with references to Orwell, Johnny Rotten and Wodehouse. Mamoon is an engaging monster, drawn from Kureishi's grandfather, but also an idealisation of Kureishi's alter ego, an internationally respected literary man. The closing lines of the novel tell us all we need to know about Kureishi's current self-image: "He'd been a writer, a maker of worlds, a teller of important truths. This was a way of changing things, of living well, and creating freedom."