Swing a cat on the App Store – boots optional – and you'll hit hundreds of rubbish fairytale apps for kids. More grim than Grimm.

One of the publishers to have bucked that trend is Nosy Crow, the British children's publisher that has built its business on a blend of traditional (print) book publishing and a series of critically-acclaimed book-apps.

Its Three Little Pigs, Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood show it is perfectly possible to make a fairytale app with craft and care, while ensuring that interactivity and inventive use of device features like the camera and accelerometer don't detract from the app's main purpose: storytelling.

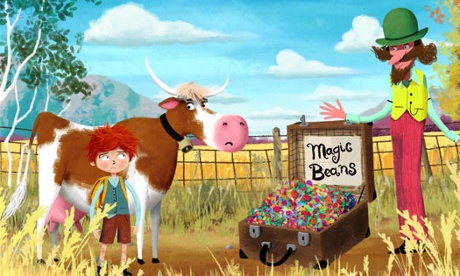

Now Nosy Crow has released a fourth fairytale app, Jack and the Beanstalk, which is its most ambitious yet. "Interactivity is built into the app more so than before. It looks quite game-like, and it's consequence-driven in a way that's quite game-like too," says Tom Bonnick, the company's digital project and marketing manager.

"It's an app that rewards your success with more story, which feels like a really positive thing to do, in terms of encouraging reading for pleasure. We've always tried to avoid interactivity that was tacked on: interactivity is what drives the story forward, and propels the narrative."

There's a sensitive debate going on around books, apps and children within the publishing industry, fuelled by fears that children may be turning away from reading in favour of games. A survey of 2,000 British children and parents conducted by Nielsen Book in 2013 suggested these fears may not be unfounded.

Jack and the Beanstalk is the latest example of a product that's trying to get beyond a simplistic 'books good, apps bad' response to these trends. "We made it with younger boy readers in mind, maybe who are reluctant to read too much on the page, but who are comfortable with on-screen gaming experiences," says Bonnick.

"We thought this was a good way to bring them back to stories and reading experiences. There's a lot of story, with text on every page, and a lot of incidental dialogue: characters who talk when you touch them."

"We'd done two stories with female protagonists in a row, and while girls will engage with boy protagonists, it's harder to get boys to engage with girl protagonists. I wish that was not true, but I'm sad to say my commercial experience is that it is true," adds managing director Kate Wilson.

"Jack was interesting though: we did introduce women into the story more than is generally the case with this fairytale: we have quite a lot of incidental characters who are female and voiced by girls, rather than just the traditional naggy mum and housekeeper."

Nosy Crow thinks a lot about this kind of thing: the mums in its last two fairytale apps have been deliberately shaped like... well, shaped like mums: normal women. Cinderella, meanwhile, was feisty rather than fairytale-princess – another deliberate design decision.

"We didn't give her Barbie proportions, and if you use the app, you'll notice the prince never refers to how she looks. He says 'you have a nice smile... you're so easy to talk to... you're friendly'. It wasn't about her coming into the ballroom and him thinking she looked fantastic. We made it about their personalities."

Nosy Crow builds its apps in-house – a point of pride for the company – with a development team drawn from the console games industry to complement its core publishing skills. Bonnick says the result isn't a clash of cultures, but something more unified.

"We share a common vision: it's not half of us saying 'make it really gamey' and half saying 'make it really booky'. What works well is that we have a shared set of beliefs about what our apps should be like, and what's going to appeal to children."

Like previous Nosy Crow apps, Jack and the Beanstalk swerves some of the elements of the story: the giant doesn't get killed on-screen, just as the first two little pigs didn't die in the company's first fairytale app – they ran to shelter in the third little pig's house of bricks instead.

That's a deliberate creative decision by the company, with Bonnick accepting that there is more freedom to include the "darker" material from fairytales in books, but suggesting that there are good reasons to leave them out of apps.

"The nature of the apps is that they're so interactive, you're implicated in the action. The user is performing these actions and tasks themselves, so retaining the violence from the original texts mean you get eaten by the wolf, or you throw the witch into the oven," he says.

"That sort of violence becomes a bit difficult: you're being implicated in a way that you're not as the reader of a print book, where arguably it can be quite helpful for children to read about some of these things at a young age."

'You can't have just a linear flow of dialogue...'

Jack and the Beanstalk is nevertheless pitched slightly older than the company's previous fairytales, if not in darkness then in difficulty. Its story sees Jack exploring nine rooms in the giant's house, each with their own mini-game that – while accessible for children – offer more challenge than in previous apps.

This isn't so much about Nosy Crow's audience growing up with the company – five year-olds who used The Three Little Pigs when it came out in February 2011 will be seven or eight now – and more about the company's expanded creative ambition, and the impact of Apple's new Kids category on the App Store, which requires publishers to choose one age category for their apps: "5 & Under", "6-8" or "9-11".

"Because we only have this one channel to market, we have to decide whether this is more of a pre-schooly thing or more of an emerging reader thing," says Wilson. "We said this was more of an emerging reader thing, which pulled it into an older age group a little bit."

Both Wilson and Bonnick talk animatedly about the challenges of the apps market for a children's publisher, including deciding in 2013 to release fewer, more ambitious apps rather than Nosy Crow's flurry of releases in 2012, and the difficulties of finding authors who are fully suited to the demands of mixing linear and nonlinear storytelling.

"In Little Red Riding Hood, we learned a lot about having core narrative delivered, and then dialogue floating on top of that. It's two kinds of things, and we don't find many writers coming to us with that ability," says Wilson.

"When I receive submissions for app ideas, they're often conceived in the way someone might conceive of a book idea, or some people come up with what looks like a TV script. But in these kinds of apps, you can't have just a linear flow of dialogue," agrees Bonnick.

That brings us back to games, where this kind of storytelling – some linear narrative but then a lot of additional storytelling coming from non-player characters' dialogue – is par for the course. A way games can influence book-apps in a way that's more than just breaking up the narrative with mini-games.

Nosy Crow did well from Apple's Kids category: many of its apps were featured by Apple when it went live last year. Wilson doesn't shirk questions about children's apps as a business though, admitting that it remains hard work for any publisher focusing on paid book-apps rather than games with in-app purchases.

"The tough thing is that a lot of people expect everything for nothing, or at least for very little. At the moment, it's hard to say that the price these apps are commanding is a reflection for the effort, expertise and thought that goes into them," she says.

"How do people think we pay the bills in Sainsbury's? How do they think we live? We can't make stuff and give it away unless there is some kind of financial model backing it. We have chosen to go with app-by-app sales, and that is proving tough. But all of this was worth the experiment."

Nosy Crow's apps have had a positive impact on the company in ways beyond revenues: it has won several awards for innovation, boosting its profile within the publishing industry. It is also exploring turning some of its apps back into print books: one non-fairytale app from 2012, Animal SnApp: Farm, evolved into a book (and then, again, an app) called Flip Flap Farm.

"We found that the apps are incredibly content-rich: there's much more in any of our apps in terms of artwork than there is in the books that they might have sprung from. So we are looking at doing a few more projects reverse-engineering things back out from apps to books," says Wilson.

"Also, we're absolutely in the app marketplace, and we have no plans to leave it. But even if the 'app' isn't how the interactive storytelling mechanism remains forever and ever, all the things we've learned about constructing these stories will have made it a really valuable experience."