In 1967, the American composer Morton Subotnick released a record called Silver Apples of the Moon. It was the first electronic album ever to be commissioned by a classical record label, and it is still revered among synth gurus for containing the seeds – or possibly the pips – of techno.

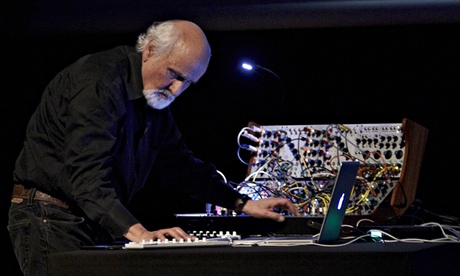

Now 80 years old, though looking at least 20 years younger, Subotnick has flown halfway round the world, from his home in New York to Australia, to perform Silver Apples of the Moon in its entirety at the Adelaide festival. But what he's really excited about is a new app he has created that enables kids to create their own electronic compositions on an iPad.

The app – called Pitch Painter – could be seen as the fulfilment of Subotnick's prophecy, made in the 1960s, that one day every living room would contain a synthesiser. Having downloaded the app, I'm eager to play him the jaunty little electro-nursery rhyme I've come up with. "That's very good," he says. "A three-year-old could have done it," I reply.

"That's exactly the point. It's a way of enabling kids to create music intuitively, without standard notation getting in the way. You wouldn't prevent children from expressing themselves in paint before they've learned to draw, so why shouldn't they be able to compose without reading music?"

Subotnick himself studied music at Mills College in Oakland, California, where his fellow students included future minimalists Terry Riley and Steve Reich. He was all set for a career as a clarinettist, but his interest in electro-acoustic music led to the establishment of the San Francisco Tape Music Centre in 1961, with fellow musician Ramon Sender. The two men dreamed of creating compositions with sounds no conventional acoustic instrument could produce. So, with a $500 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Subotnick commissioned electronics wizard Don Buchla to build an "electronic music box".

For his performance of Silver Apples of the Moon, Subotnick will be using a modern re-creation of the first Buchla synthesiser (the original is now in the Library of Congress). It looks more like a miniature telephone exchange than an instrument, which may explain why it never really caught on. Shortly after it appeared, Robert Moog debuted an alternative that was adopted by the likes of Pete Townshend, Micky Dolenz and Wendy Carlos, whose Switched-On Bach, recorded on a Moog, became one of the biggest-selling classical releases of all time. Not that Subotnick was impressed. "I could never see the point in playing old music on a new invention," he says. "If I'm going to play Bach, I'd rather use a harpsichord."

The Buchla might not have caught on, but that didn't stop Subotnick making full use of it. Almost 50 years on, Silver Apples of the Moon still sounds arrestingly contemporary. The piece is in two parts: the first is slower, moodier and full of profound, synthetic sighs, like a robot in despair; then in the second half, something extraordinary happens – the music suddenly develops a pulse and climaxes in the frenzied hammering of proto-club rhythms.

This had simply never been heard before. Early electronic compositions were mostly about sine waves, oscillations, timbre – all devoid of rhythm, by and large. Yet, says Subotnick, his discovery of beats happened almost by accident. "In the early days, it took a long, long time – sometimes even days – to programme a sequence. Quite unintentionally, I found I had created this pulsating rhythm. I started grooving with it – and it blew my mind."

And quite a lot of other minds, too. Silver Apples swiftly became an essential psychedelic soundtrack. "I certainly wasn't on drugs when I made it," he says. "I was working too hard. But I'd been staging multimedia performances with dance companies using projections and coloured oils since the early 60s, which was several years before psychedelia is supposed to have started."

Even the album's trippy title is perhaps a little less trippy than it appears: Subotnick took it from Yeats's poem The Song of Wandering Aengus: "The silver apples of the moon, the golden apples of the sun." As Subotnick says, "It doesn't really mean anything. I just liked the sound of it."

More innovations followed. Subotnick's 1994 work All My Hummingbirds Have Alibis was the first interactive concert to be conceived for CD-Rom. And in 1995, he produced the first of his children's works, Making Music, which might be described as the young person's guide to the sequencer.

But it's Silver Apples he will always be most closely associated with – and that suits him fine. "It's not a bad little piece," he says. "It's like a jazz composition. I'll start out with some of the familiar riffs, then just improvise. It keeps on changing whenever I perform it."

• Silver Apples of the Moon is at the Adelaide festival on Friday, 7 March. The festival runs until 16 March (adelaidefestival.com.au). Alfred Hickling's flights were provided by Emirates.