Derek Jarman wandered into theatre, as he did into much of his creative life. The stage design department at the Slade School of Art in 1963 was casually structured, and, for the era, an uncloseted zone of gaiety. He'd previously slapped a distemper brush on scenes for Lorca's Blood Wedding and other plays put on by fellow students at King's College, London. He had not seen much theatre, as movies – even concerts – came cheaper; the first production that really excited him was Peter Brook's short and gory staging of Antonin Artaud's Spurt of Blood in the RSC's 1964 Theatre of Cruelty season.

Jarman put a lot of effort into his design course, outlining a surreal play, The Billboard Promised Land (a mashup of The Wizard of Oz and culture shock from his brief escape to the US), and producing the required portfolios of stage projects. The latter included Orpheus, with a Richard Hamilton-ish collage of male nudes clipped from the magazine Physique Pictorial, and a painterly design for Prokofiev's The Prodigal Son, later shown in a Paris exhibition.

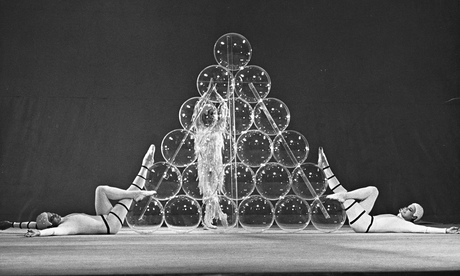

There was less riding on artistic gambles in the 1960s, and taking casual chances on unknowns was commonplace. In 1967, the choreographer Frederick Ashton, liking what Jarman had displayed in Paris, commissioned him to do sets and costumes for Ashton's ballet Jazz Calendar for the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. The production, which starred Rudolf Nureyev and Antoinette Sibley, was plotless froth for a quick fill-in, and Jarman gave it larky, spare graphics. The costumes made the cast look like liquorice allsorts in motion (Sibley had a bubble wig) and there was even a pyramid of clear Perspex balls, the toy of the moment.

It was a success. John Gielgud immediately asked Jarman, dear boy, to design Don Giovanni for Sadler's Wells Opera at the Coliseum. The brief was Goya, and Jarman delivered De Chirico geometric; reviewers complained of "a cross between the Drug Store and the Swiss Centre" (then London's latest retail venues). The designs now seem spare, calm – and not that dated. Nonetheless, Jarman's stage design career was, in his own words, "brought to a halt, not a moment too soon".

He lived theatrically, though: residence as performance. In the Thameside warehouse spaces he rented cheaply (the stage-mad were drawn to the melodramatic dereliction of Bankside long before there was any thought of a new Globe), he hung up swoops of homemade capes as decor. Ken Russell signed him as a designer for the The Devils in 1970 after seeing those capes, sure that Jarman could come up with an opera house screenscape. He did just that, producing a pale, abstract city, white-tiled nunnery and mighty wooden stage machinery: the Royal Opera House would've loved it.

When Jarman decided he wanted nothing more to do with the movies unless he was behind his own Super 8 camera, Russell – about to direct Peter Maxwell Davies's opera Taverner – tried to tempt him into designing the Royal Opera House production. Jarman got as far as suggesting lighting the auditorium blue instead of blusher pink, costuming the orchestra, and hanging dead cattle up with the chandelier (he had never forgotten Brook's cruelty). Ralph Koltai got the job instead.

When Jarman did pick up a stage gig, it wasn't always entirely right on the night. His visual ideas for a 1973 Festival Ballet piece, Silver Apples of the Moon, looked delicious: a stage hung with hundreds of half-silvered bulbs suspended on transparent flex, a lunar precursor to the amber flash and dazzle of the National Theatre's 2011 production of Frankenstein. The audience at the Oxford premiere gasped when the lights were suddenly switched on, but the show was withdrawn from an intended London Coliseum slot because of worries over "nude" bodystockings. (Jarman had already had a run-in with the Ballet Rambert over padded bodysuits with breasts and penises.)

By then he was a film-maker of shorts, but still conceived his big projects in terms of live theatre. In 1975, the just de-railwayed Roundhouse inspired his first thoughts about The Tempest: Prospero's magic cloak would expand to a huge banner and the mariners would cling to the rigging of their ship as it went down in a flooded arena, while the audience was safe on trampolines. It was a cinema spectacular of a theatrical concept, where Jarman's later movie version was more like a recording of a staged masque. His memoirs (and the recollections of those who acted in his films) describe his way of working as staging stuff live, almost like a theatre rehearsal, while trying to film events as they happened.

There were tiny stage jobs, such as a ballet backcloth for a one-night gala that he painted with orchids from a favourite childhood book, Beautiful Flowers and How to Grow Them. Once he began making feature films, however, he returned to the stage only when he couldn't say no. Because he was broke in 1982, he said yes when Russell asked him to design Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, at the Teatro Della Pergola in Florence, in a tearing hurry (nine sets and all the costumes in 10 days). They agreed it was to be set in Thatcher's Britain (she appeared as a vampire), with a dinosaur skeleton by way of a proscenium arch; the good girl was arrayed as Lady Di and the brothel madam as the queen mum. The opera company Teatro Comunale di Firenze were proud of the just-post-punk British mise-en-scene, with black bin bags heaped onstage and a phoney Hockney on a wall, but there was an onstage confrontation with management over the permissible length for giant phalluses.

Never mind: they asked him back in 1987, this time to direct Sylvano Bussotti's L'Ispirazione. His misgivings proved right. He regretted turning into a caricature Englishman abroad, shouting ever louder at cast and crew to compensate for his modest Italian. For the opera's videoclip backing, he brought Tilda Swinton with him as "Mistress of Theatre and Space" (her job description for life). The show went on fine, but not for him: he found Florence mildewy and rowed with Swinton, planning his film of Edward II as light relief. Jarman had worked out that videoclips shouldn't be rival, simultaneous, productions, but stage sets in motion, with gaps left to frame the live action.

When Jarman directed concerts for the Pet Shop Boys tour, culminating at Wembley in 1989, Neil Tennant said he did the gig "in the same way you direct musicals". The band became part of a stage collage: live and noisy cutouts from Physique Pictorial.

Jarman did one more stage design, for Waiting for Godot at the Queen's theatre in 1991. It was a period piece with a stunted tree on moulded rockscape, as though he were going back to the earliest theatre he'd seen, perhaps out of courtesy to Beckett. What if he'd imagined it as happening on his own final domestic set, on the bleak but not all blasted shingle of Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, with driftwood, purple-rooted seakale and the boom of the foghorn?

• Jarman 2014 is a year-long series of screenings and exhibitions celebrating his life and work