Exactly a year has passed since the marketing agency for British national newspapers – Newsworks – brought ad people together for its annual jamboree and started the day with a keynote address from Tony Gallagher, editor of the Daily Telegraph. He told them about holding editorial conferences via iPad, generating two-and-a-half times the digital copy that made it into print every day, plus many other wonders of transitional hi-tech life. Rapturous applause. And where is he now? Learning to cook tapas in Clerkenwell, as it happens. Meanwhile, the lead speech for Newsworks' 2014 revels this week will come from Jason Seiken, now editor-in-chief and "chief content officer" of the two Telegraphs. Twist of lemon with your salt cod, sir?

One all-embracing theory has followed Seiken since Gallagher was suddenly dumped three months ago. As advanced by thoughtful observers – such as Kim Fletcher, former editor of the Sunday Telegraph – it argues that old-style Fleet Street editors have had their day. Bring on the "content" squad. See how digital life, lived bottom up rather than top down, is the form of the future. Seiken – from AOL and America's Public Broadcasting Service – supposedly shows us where we're going, not where we've been. The "imperial editor" is on the way out, he says. The empowered customer (aka the reader) needs his "me" time, his opportunity to create his own agenda.

Already the office doors in Telegraph Towers offer an array of titles only the BBC could love. Not just boring old "directors of digital content" but a director of "editorial transformation and talent" and a "general manager, lifestyle". Meanwhile, the daily print paper has a Monday-to-Friday editor, while Saturday and Sunday are under consolidated rule. It all seems cutting edge, pell-mell and (for a deeply conservative journal with an elderly age profile) pretty unlikely too.

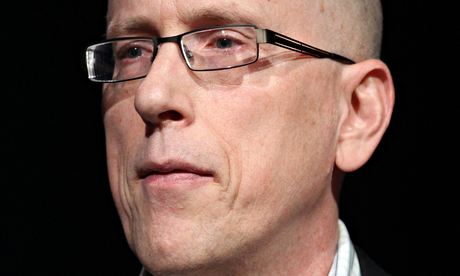

But then Seiken himself is a pretty unlikely figure: not Silicon Valley stereotypical, but a lanky, very amiable East Coast liberal who worked as a journalist in Boston's suburbs long ago before running the Washington Post's website. He happens to hold a UK passport, but in every evident respect he's American. Nothing wrong with that: if the last DG of the BBC can lead the New York Times, who can gripe about two-way traffic? What seems more unexpected, though, are the early policies – slightly imperial ones – he's made his own.

Should Telegraph reporters be allowed to file directly on to the web? No: they need intervening site handlers – aka subeditors – to guard against egregious error. Does the pace and prolific range of the internet make news diaries and careful event planning, with attendant conferences, seem redundant? No: call a meeting. Who, in an era of flux, wants career planning and established promotion patterns, the reassurance of vulnerable humans properly resourced? Apparently the Telegraph needs that as well. And maybe, once you start talking the continuing importance of the profit-making papers in print, there needs to be a reconciliation of old and new values as well.

The old Tory daily built its quality circulation and reputation on news piled high. There's no glowing website future, apparently, in becoming just another celebrity-stuffed Mail Online clone, still less a trailing sub-Mail in print. That's a "me" too far. Any new dawn breaking over the towers, it appears, has to pay due obeisance to existing revenue streams. Nobody, looking at the balance sheets, thinks of the print papers as lifeboats to be abandoned soon in the surge to some distant digital shore. And it's Seiken's fundamental job, of course, to keep all this in balance.

Yet balance inevitably involves pace and direction; and this is where the mists begin to gather. He'll talk this week, as he talks to his staff, about "imperial" renunciation, the absolute necessity of change for that "me" generation. Understood. If you're trying to attract, and keep, skilled computer hands, for instance, there's a need to compete here. But how far and fast can such change go? The Telegraph isn't a Buzzfeed, a Mashable, a Vice. Its staff chatter to Private Eye, not Gawker. And there's a fundamental difference, which Seiken also seems to see well enough, between mere clickfests – the top 10 celeb tales of the moment, say – and a properly honed, considered version. So editors, after all, have their uses.

But do they hire and fire (or get "transformation and talent" to do it for them)? Do they stay close to the twists of politics as an election nears, or let leader writers and lobby correspondents chart their way? Are they in charge – legal as well as moral charge – when a front page goes to press? Of course there are basic differences between print and online: selection versus inclusion plus promotion. But bloggers – like Guido Fawkes, like the Telegraph's own Ben Brogan – have a sharp-elbowed angle, a point of view. They're not just another Buzzfeed list. And British print papers (as opposed to America's regional-monopoly press) need that point of view. They exist by cultivating and serving separate audiences. They are different markets with different traditions and expectations.

The question for Seiken and his Telegraph masters, then, involves the difficulties of difference. We know some newish global news sites – the Buzzfeeds, the Vices – can make a profit, because (among other things) they're not newspapers, not staffed and resourced to ape that model. We know that web startups which have tried to follow the paper trail – Murdoch's The Daily, Tina Brown's Daily Beast – have had a very rough time, and that even the HuffPost has its white-knuckle moments. We know that a solidly profitable FT website has a supreme imperial master, Lionel Barber. We know that the most visited UK newspaper site, the Mail, preaches separation, not integration: it grows by not being the Daily Dacre online. It has its own imperial editor, Martin Clarke.We know that when the Telegraph wades into the Maria Miller row it's Gallagher who stokes its flames.

So why do we axiomatically assume that a digitally led and transformed Telegraph is the future? Is success for Seiken rising print circulation, rising unique browsers, rising profits? Is failure a choice from that same array, any or all of the above?

Put a guru in charge and problems gather naturally. Seiken is a clever, affable fellow: he deserves a chance. But content is only the beginning, not the end of this digital affair – and that's all about "him", his vision, his clarity, as well as about "us". Maybe open-minded print emperors can move into digital fields and prosper. The problem now is whether that transition can work the other way around.