Scripted by Sydney Boehm, a specialist in westerns and crime movies whose best film is perhaps Fritz Lang's The Big Heat, and directed by genre specialist Richard Fleischer, Violent Saturday is a noir thriller in Technicolor that brings together in 90 minutes a key location of the 1940s and 50s with one of those decades' favourite plots.

The setting is a corrupt, middle-American township (key examples being King's Row, Peyton Place and Some Came Running). The opposite of the cosy hometown of Andy Hardy movies and nostalgic Tin Pan Alley songs, it's seething with hypocrisy and inhabited by snobs, alcoholics, thieves, voyeurs, blackmailers, adulterers and womanising playboys. The plot is the heist movie, the story of a carefully prepared robbery, which has been around since The Great Train Robbery (1903) but became an established species of the crime genre in the postwar years in The Asphalt Jungle, Criss Cross and The Killing.

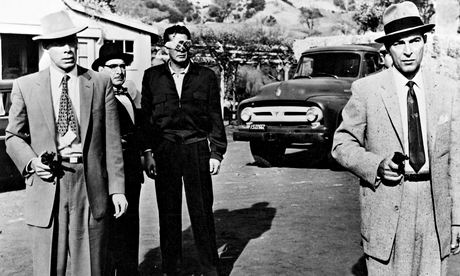

Violent Saturday takes place over some 36 hours in the Arizona town of Bradenville, a community dominated commercially and physically by the copper mine, and its first hour is spent establishing its troubled key inhabitants, from the local mine owner (Richard Egan) to the Peeping Tom bank manager (Tom Noonan), and the three suave, hardened criminals who arrive to rob the bank (Stephen McNally, Lee Marvin, J Carrol Naish). There's little morally to choose between the citizens and the crooks, though a peaceful Amish farming family (paterfamilias Ernest Borgnine) living outside town are, on the face of it, the only truly innocent people around. Then the well-planned heist gets under way at 12.55pm Saturday, the two sides come into conflict as all hell breaks loose and everyone reveals their true colours.

The movie is carefully orchestrated, the letterbox CinemaScope screen is skilfully used to locate the characters in relationship to one another and to the place itself, and for once the victims of the crime are as firmly established as the predators when the conflict begins. The movie is a little masterpiece that reflects the tensions beneath the conformity of the Eisenhower years, and it's accompanied by a shrewd pictorial essay by the French critic and film-maker Nicolas Saada.