Last year, Russell Brand caused another to-do. This time he wasn’t playing nasty jokes on Andrew Sachs, or boasting about the millions of people he’d slept with; he wasn’t calling George Bush a “retard”, or giving a Nazi salute at the GQ awards, or turning up to work dressed as Osama bin Laden (as he did the day after 9/11), or stripping naked to cover the May Day protest for MTV. No, this time he simply made a political statement.

Brand was asked to guest-edit the New Statesman, and chose revolution as his theme. He agreed “because it was a beautiful woman asking me”, associate editor Jemima Khan – not the most revolutionary reasoning. He then admitted he had never voted and encouraged others not to, in order to nobble the establishment. A few weeks later, he was grilled on Newsnight by Jeremy Paxman: who was he to advocate revolution, a here-today, gone-tomorrow comedian, an apathetic whinger who couldn’t even be arsed to exercise his democratic right, a “very trivial man” who believed in nothing?

One year on, Brand has got his answer. Now, his revolution isn’t just a throwaway comment. It’s a new book, a slogan on his necklace and, he believes, a real possibility. The book is a classic Brand potpourri: brilliant and infuriating, part travelogue, memoir, rant, riff, a call to arms and, ultimately, to love. It is not as readable or funny as his two Booky Wooks; more stream-of-consciousness tract. In short, he argues that the planet is being destroyed, the poor are being shafted, the rich are getting richer and he has had enough.

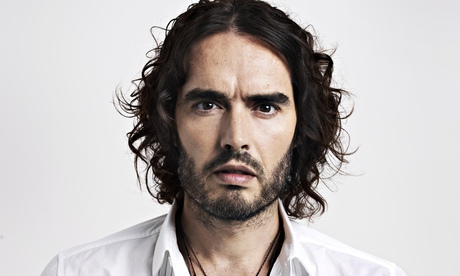

We meet in a pop-up cafe close to his Shoreditch home. Young trendies run it; even younger trendies sit at long tables sipping complicated coffees. When Brand arrives, he is starving and quiet. Intensely quiet. “I am bleak with hunger,” he says. I had always thought of him as seedy – a walking STD in skinny jeans – but he looks surprisingly wholesome: lovely olive skin, Malteser-brown eyes, well-washed, tactile (more knee patting than you’d get off Terry Wogan in his prime).

Dan, the manager, is making Brand an almond latte and avocado toastie. He says the coffee’s been made with love, gesturing with a knife. “What is the ingredient the rest of the time, you knife-wielding charlatan?” Brand asks. Like Adam Ant’s dandy highwayman, he’d have been in his element in the 17th century.

He is talking so quietly, I can barely hear him. He doesn’t just seem bleak with hunger; he’s bleak with bleakness. He explains how he decided on the interviews in his book, with Naomi Klein, anarchist David Graeber, economist Thomas Piketty: people who could help him make sense of his political vision. “I wanted to do it from a perspective that is accessible. I didn’t want to come across as pedagogical. Is that right, pedagogical?”

Blimey, Brand is checking a word with me. This is nothing like the motor-mouth on the telly, laughing in the face of everything. He says he has always been political, and refers me back to one of his first TV shows: a documentary in which he hung out with the head of the young BNP in Leeds, challenging him on his views. It’s interesting to return to that show – Brand looks so young, all puppy fat and pasty-faced, yet in many ways he was already fully formed: super-smart, self-adoring, brave, a brinksman on the verge of getting a kicking.

“I was still a drug addict back then, on crack and smack.” Didn’t that make it hard to work? “God, no. If you use them in conjunction, they are the coffee and alcohol of the illicit world, providing enough animation to get things done, enough opiation to keep me relaxed.” Actually, he says, he’s being glib. “Crack makes you so fraught, it’s unbearable. It’s just amplifying the anxiety attack that was my modus operandi. Heroin is like a panacea for angst.” Even though he’s been clean for 11 years, Brand still often talks about drugs in the present tense. He is one of life’s natural addicts – not just drugs, but sex, work, success, avocado on toast. Politics, even.

If he hadn’t got waylaid by success, he would have been banging revolutionary drums long before now. “I always wanted to do something worthwhile, and more than the self-aggrandising pursuit of fame. There’s all sorts of opportunities if you’re an ambitious and narcissistic kid, and that’s the direction I ended up going down.” Fame – another addiction. “I came to realise it doesn’t do anything, has no value. It’s not going to be enough, like all the addictive behaviours I’ve pursued are never enough. They are, what’s the word? Sisyphean.”

Brand says it is a misconception that druggies have no drive. He was always driven. He was brought up by his mother in Grays, Essex. His father, a photographer, left when he was a baby. An only child, he adores his mother, who was diagnosed with uterine cancer when he was eight, then breast cancer a year later (she recovered, but was diagnosed again earlier this year). By 14, Brand was bulimic; at 16, he left home after falling out with his mother’s partner, then discovered drugs.

A lonely, insecure boy, he had grandiose ambitions. After appearing in a school production of Bugsy Malone, he didn’t simply assume he was destined for superstardom, he was already working out how he’d use his fame to change the world. “I narrativised my own impulse incredibly quickly, from doing a school play to thinking, ‘I want to be a movie star’, to thinking, ‘God, that will never be enough. I have to use this influence to talk about important issues that affect people.’”

At school, people found him funny, often for the wrong reasons. What would they laugh at? “My manner. I can’t escape the Kenneth Williams, Michael Crawford, Frankie Howerd music hall campness of our country. That’s in me. However much I try to channel Marc Bolan, I’m still a bit peculiar. I’m at ease with that now. I didn’t feel at ease growing up in Grays. You want to be good at football, good at fighting.” Was he good at fighting? “I’m a lunatic, so I’ve got a thing in me where I can go, oh well…” But no, he says, not really.

He went to the local arts college and won a place at the Italia Conti theatre school, where he was expelled for drug use and poor attendance. From then on, he relied on his own wits – acting, writing, gigging, presenting, agitating.

The first political rally Brand went on was in London for the striking Liverpool dockers in the late 90s. “There were police horses galloping up Charing Cross Road, people ripping up pavements. I didn’t think [he puts on a posh voice], ‘About time, too – the Liverpool dockers are finally being heard here.’ I thought, ‘Fuckin’ hell, this is brilliant.’” He related to it on a personal level. “The internal mayhem I’m feeling is spilling out everywhere. I loved it, and felt very connected to activism – particularly activism that feels loaded with potential. Not the oppositional activism that seems like there’s a stasis around it – earnestly sincere, but a monolith equal to the establishment.”

There has always been an element of mayhem to Brand’s career, his hunger for success at times trumped by his knack for sabotaging it. Hosting an MTV awards show in the US in 2008, before Obama had been elected, he said, “People say America will never elect a black president, but I know America is an advanced equal opportunities kind of country. After all, you’ve had that retarded cowboy in the White House for eight years. In my country, he wouldn’t be trusted with a pair of scissors.”

He returned to his hotel room to celebrate his brilliance. “Helium balloons were filling my room. I remember waking up next morning and Googling my name.” For 24 hours, his name was the fifth most Googled thing in America. “I was sitting in the room, reading all the negativity and death threats, and by now the helium balloons were half-full, hovering like jellyfish. My agent said, ‘Well, we wanted people to know who you were, and now everybody does, but not a lot of them like you.’”

Did he regard it as a triumph? “No, I felt a bit scared. It was like, ah, no, I misjudged that. The feeling’s hard to articulate, but it’s like a hunker-down mentality that happened with Sachsgate and a few other times.” Is he addicted to professional risk-taking? He sprinkles pink Himalayan salt over his avocado toast and bites into it. “Yes, I think so.” He shouts out to the manager. “Thank you, Dan, this is lovely. I’m excited and confused by the salt. What a ludicrous pursuit. Who’s going to the Himalayas and coming back with pink salt?”

In retrospect, he says, the early days were great. “The first flush of fame, the Big Brother type, was brilliant. Oh my God!” But then he’d want another level of celebrity, achieve it, and get more bored and disgusted. “It’s easy to start thinking, being on E4, doing Big Brother, is a bit shit. Maybe it would be good to get my own show? Maybe it’ll be better if I’m making movies. And each gradient achieved doesn’t nullify the sense that it’s pointless.”

When was it most pointless? “Hosting big award shows and making big movies. It’s like vacillating between a huge anxiety attack, hosting those shows, to the grinding tedium of being hunched in trailers and doing makeup tests.” He pauses. “Perhaps I’ve not made the right type of films.”

What’s the worst film he’s made? “When I did Arthur, I did that with a certain intention. Looking back, I think, ‘Ugh, I probably shouldn’t have done that.’” What was that intention? “Doing a big film.” He shagged his way around Hollywood, married pop star Katy Perry and famously divorced her by text (he insists it wasn’t as simple as that), became addicted to transcendental meditation and began to question his old way of life. Did he get bored with all the sex? “When I got married, I was becoming a bit bewildered and exhausted.” Had sex become a commodity? “It is very easy to look for comfort in anything that takes you out of your head. I was transfixed by that avocado, I couldn’t think of anything else. I just fixate on something simple that’s got an orgasm at the end of it.”

On his return from America, he fell in love with Jemima Khan and found himself becoming more politicised. I read an early draft of Revolution and it feels like a love letter to Khan. When I tell him this, he looks surprised, even slightly put out. “Why’s that?” Well, because it is so adoring of her, as a muse and a mentor. Is she the main influence behind his politics? Now he looks positively disgruntled. “Like I said, these things were always in me. Politics is not something I’ve acquired through academia or influence, it’s something I’ve acquired through growing up in a single-parent family, being on the dole, then being a drug addict. There’s a lot of anarcho-collectivism in the fellowship around abstinence-based recovery. I didn’t read about politics, I felt it, then picked up a bit of jargon and lingo. Certainly this has been a huge learning curve the last couple of years, and I wouldn’t want to diminish the role of Jemima in that, but neither would I want to be so glib as to say it’s down to her.” Soon after our interview, it is reported that Khan has split with Brand; parts of the draft I read have since been substantially revised.

For the past year Brand has been airing his views on the Trews (or the True News), a daily YouTube broadcast. In recent weeks, he has discussed democracy in Hong Kong, the importance of embracing real politics by ignoring Westminster, and whether Obama should give back his Nobel Peace prize. In the book, his conclusion is simple: capitalism is kaput, celebrity charity won’t plug holes, revolution is the only solution. Yet it also feels like a bit of a cop-out: he insists all this can be achieved through love, peace and understanding.

Would he ban private education? “Yes.” And private health? “Yes.” He would “cull corporations” after they have served their purpose. Does he really believe all this can be achieved without coercion? “Yes.” How? “By focusing on the important issues. We’re not even talking about moderately wealthy people – we’re talking about a society so unequal, so ludicrous, that 85 people have as much money as the 3.5 billion poorest in the world.”

It’s stifling in the cafe. My phone rings and I take the call. Brand seems worried that he’s losing my attention. “It’s really hot in here, it’s unnatural,” he says. And before I know it, we’re heading out. It’s obvious we won’t get much peace outside, but Dan has an idea: “I’ll half pull down the shutter.” There is a gap between the window and shutter, and we sit on the ledge. Brand’s head is hidden from public view, but his voice and legs are not.

The move outside transforms him. He gulps in the air and starts speaking twice as fast and 10 times louder. “Yeah, and what I think is, the book’s just the start of a conversation. I don’t know what you do about private education or private fuckin’ anything – I’m not a bloody politician. I want to address the alienation and sense of despair that you see all around us. Everyone’s fucked off, everyone’s had enough, so it don’t matter to me how much people have a go at me, because I live in the world and walk around, and people are going, ‘Well done, Russell, well done, son.’ I’m ready, I’m ready, I’m ready to die for this.” He finally takes a breath. “Yeah, I’m ready to die for it.”

Wow, I say, it’s amazing what a bit of fresh air does for you. He grins like a shark. “Yeah, I love it out here. This is where I belong. When I look at them Eton-educated people that govern us, I ain’t afraid of those people. I am excited. I’m going to enjoy this like nothing else, because for once I’m on the right side of the argument. And this is the right time. I feel it. I feel it. The means exist.”

I ask if he normally talks so fast. “Yes. Yes. So now, why I’m excited and why I endorse not voting, is because the farther politics drifts to the right, the better it is. Good. Antagonise people. Let’s get to the point where people are no longer just satisfied with iPods, iPads, iWatches. To the point where people go, ‘I’ve had enough.’” Is he advocating rioting? “It doesn’t have to be through rioting. It can be through total disobedience, non-payment of taxes, non-payment of mortgages.”

Caring capitalism was a blip, from 1945 to the end of the 70s, he says: a one-off created by the second world war and the founding of the welfare state. “Capitalism is going to continue to increase inequality. And people are preparing now for what follows capitalism. If people are informed and activated, it will be something that’s more liberal and fair; if they’re not, it will be draconian and terrifying. I think people in power are preparing for the latter. That’s why $4.2bn worth of military equipment has been transferred to local police authorities in America over the last 15 years. Why London authorities are buying water cannons and why Thomas Piketty’s book is causing such a stir.”

Even though only his legs are visible, there is no disguising him. Roll up, roll up, for the Russell Brand revolutionary show. And they do. Within seconds, people, largely young men, are approaching, giving the thumbs up, screaming their approval or joining us under the shutter. Nobody wants to talk about his gigs or acting; there is only one thing on their mind: the Trews and politics.

“People support the Trews,” a well-spoken young man says. “He’s having an impact on the psyche and the spirit and the global consciousness.”

“Say it again, because this man’s interviewing me for the Guardian and you’re making me look good,” Brand says.

“This gentleman here is a proponent of the truth,” the young man continues. “His only agenda in life is to disseminate unadulterated facts in a hopefully unbiased way.”

Another man approaches: “Got any spare cash?”

He hasn’t, because he’s celebrity royalty. “I ain’t got a penny, mate. You got any money, Simon?”

Brilliant, I say, digging into my pocket. I’m interviewing you about the revolution and you’ve not got a couple of quid to give to this fella.

As Brand talks to the homeless man, the posh boy says Brand has got a touch of Marx, Che Guevara and Jesus. “But really, parallels shouldn’t be drawn because he’s in a league of his own.”

Another young man joins us. He says he didn’t realise how intelligent Brand was until recently. Did he like him before? “To be honest, I judged him a bit on the way he dresses. I always thought he was a bit of a…” He comes to a stop. Cock? I suggest. “Not cock. A rich boy, a mummy’s boy. But I’ve heard him talking on YouTube recently and he comes out with some great points.” He looks at Brand. “He used to train in the same kickboxing gym as me.” Who’s better? “Nah, no chance. I’ve done competitions. He’s a bit green, to be honest, but I’d let him win every day of the week. He’s a top bloke. I love his political views.”

It’s funny, I say to Brand, that everyone wants to talk about the politics. “Well, that’s what I was saying. I don’t feel I’m looking for approval. I’m not doing it for any other reason than I believe in it.”

Are we seeing the rebranding of Russell Brand? “No, I don’t think that. I think after a while you think, ‘Oh, I’m from a suburban, low-aspirational, low-expectation community, I became famous, I thought it was going to be brilliant. It wasn’t.’ Fortunately, I had somewhere else to go.”

That somewhere isn’t simply revolutionary politics, he says; it’s politics mixed with faith. He mentions a recent interview I did with Gordon Brown, in which I said Brown had disappointed me as a prime minister. Brand talks dismissively about my “stout leftism”: if I really believed in revolution, I should be prepared to change. “I had to become someone who isn’t a drug addict any more. I had to change my beliefs. Then I had to stop being a person who was enamoured of the glistening spectacle. If you’re motivated by sufficient pain, you will change. We’re approaching a point where a significant number of people want to change.” Brand is hardly an ascetic, but he is learning about self-denial.

He received a six-figure advance for Revolution, but insists he won’t be keeping it. “I’m going to get a property in east London and set up a coffee and juice bar to be run by people in recovery from addiction.” So he’s going to give away his money? “No. I’m no longer interested in making money. And the money I get, I’m going to use for good. We need systemic change, not charity. I won’t be in charge. They’ll vote for how they want to run it.”

Is he loaded? “Yeah!” How much is he worth? “I don’t know, but I could probably never be poor again. When I see stuff in the paper like, ‘Oh, he’s worth £20m quid’, I ain’t worth that much. I don’t know what I’ve done with my money. I’ve sorted my parents out, but all the money now, I’m going to use it for social enterprises. My intention is to dedicate myself to this.” He stops. He doesn’t want to sound pious, he says: “I’m still going to do dumb stuff like The Big Fat Quiz Of The Year with Noel Fielding.” He asks if I’ve seen the film Punch-Drunk Love, starring Adam Sandler and Philip Seymour Hoffman. “Sandler is victimised by Hoffman, and there’s a bit where he eventually confronts him and he’s frightened, and he finally stands up to him and goes, ‘Look, I am a nice man’, and that’s all he says. I am a nice man. And I just think that’s enough, isn’t it? Just be a nice man.”

I tell him the posh bloke thought he was a mix of Che Guevara, Jesus and Marx. “Well, that’s very flattering,” he says, newly humble. What does he think? “Well, I’d say Karl Marx designed one of the most powerful and influential economic and social philosophies of recent history, and I don’t know whether I’ve done anything quite at that level yet. Che Guevara was a brilliant militarian. I don’t think I’d survive in guerrilla warfare. And Jesus Christ, we don’t know about him – it seems as if he may have just been a Jewish radical, so if I had to pick one… heheheheh!” He cackles like a crazy.

Does he worry about what he may unleash? People might look to you for leadership, I say; they might want you to stand for parliament? “I’m not frightened of that, but there is no room or requirement for compromise, Simon.” His repeated use of my first name is both endearing and mildly mocking. “Regardless of what I do, madness is coming. And I’ll be happy to participate in whatever way I can. But I don’t think it will be by joining an already antiquated and defunct system.” But surely he’d walk it, standing as a revolutionary independent. “Well, my ambitions go way, way, way beyond that. I’m not asking for an invitation to the party – I’m saying the party’s over.”

“On with your revolution, mate!” a passing woman shouts. He stops to stare at her. “Thank you, thank you,” he says, then dictates into my tape recorder: “‘You’re a fuckin’ star,’ she says walking by, an attractive young woman in burgundy jeans.”

Is there a danger that he’ll lead the masses up the hill, then toddle off to Hollywood and give up on the revolution? “No. I’d rather die. I’d rather die than go back to the dark.”

A few days later, Brand turns up at a drop-in for destitute asylum seekers that I am involved with. He arrives, chauffeur-driven in a black Mercedes with tinted windows, poses for any number of photos, flirts with everybody from the age of eight to 80, and listens intently to what they have to say.

Of course there are many people who will call Brand a hypocrite and say it is all very well preaching equality when he has a driver, his millions and expensive designer jeans. “Give me a chance to grow,” he pleads. “I’ll continue to improve. But I don’t care what other people think. Simon, I’m sure you’re playing devil’s advocate, but let me tell you this – the devil has enough advocates.” And now he’s screaming into the tape recorder, all passions blazing. “Be cynical. I’ve got a fantastic bicycle, I’ve got all sorts of stuff, but just give me a chance. Who cares what jeans I’m wearing? And if you want change… unless you just want to carry on doing your journalism for the Guardian and moaning about Gordon Brown, get on board when somebody’s prepared to die for something.”

• Revolution, by Russell Brand, is published on 23 October by Cornerstone at £20. To order a copy for £13.50, go to theguardian.com/bookshop.

Enter our competition

Win a pair of cinema tickets to watch Brand in conversation with Guardian columnist Owen Jones on 23 October. The Guardian Live event is sold out, but will be broadcast live to more than 200 cinemas across the UK. Each participating cinema has a pair of tickets to give away: to enter, and for terms and conditions, visit theguardian.com/russell-brand-cinema-competition before 15 October.