It would be hard to imagine a more tedious annual conference, with panel debates on “e-billing, best practices, stability and throughput” and much discussion of web analytics data and Ofcom regulation. Besides being so monotonously technical that by mid-afternoon at least two delegates are allowing themselves to listen with their eyes shut, their heads drooping forward, the atmosphere in the butterscotch-beige, windowless conference hall in the basements of an ugly Edgware Road Hilton is steeped in gloom.

The annual European adult industry trade summit (the word pornography isn’t mentioned on any of the promotional literature) comes at such a bleak time for the UK porn industry that after a few hours here you almost begin to feel sorry for these determined entrepreneurs, with their tireless attempts “to monetise content”.

“The industry is imploding,” the director of a pay-per-view adult television channel says. “If there was less free porn around, my business would be stronger.” Jerry Barnett, an industry lobbyist, and founder of Sex and Censorship, thinks the UK business “has shrunk by over 90%” in the past seven years.

Given the intensity of public and government concern about pornography on the internet, it is surprising to discover how badly those who make pornography, or who help it to be disseminated on the web, are faring. But their key problem will be familiar to those in the music industry or the newspaper business – how to generate an income from a commodity that is being widely distributed for free online.

The mood of the Xbiz EU 2014 conference is beleaguered, with panellists conferring on how to respond to new regulations requiring them to verify the age of anyone who tries to access hardcore content, whether it makes sense to escape regulation by moving their companies offshore and how best to contend with websites who disseminate pornographic content for free.

‘I blame it on hubris’

In the coffee breaks they share stories of how quickly things have turned sour for the business. “In the early days it was like the wild wild west; you could put anything up online and make a way to monetise it,” says Paul Matthews, who helps run the late porn baron Paul Raymond’s online business. Things changed when adult equivalents of YouTube arrived in 2008 (sites such as YouPorn, Pornhub and RedTube), providing limitless supplies of free videos.

“It was like a stockmarket crash. Month on month, instead of positive growth, it would fall 10-15%. There was panic. There was a lot of animosity to the tube sites. It was like you owned Ford, and then everyone started giving away cars for free.

“The tubes gave the typical surfer all the free content he would like. That has cannibalised the monetisation of all adult content. I blame it on hubris. We thought it was always going to be good, that no one would mess with our business model. We believed that people would still pay for something they could get for free.” He believes there has been an 80% drop in the number of UK businesses. “Regulation has killed it a bit too. The age-verification is killing us,” he says.

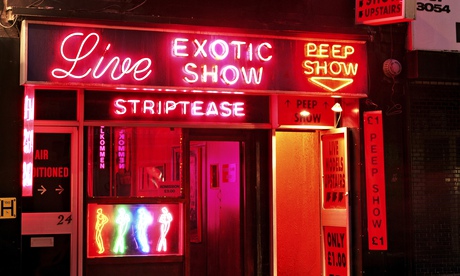

Robert Johnson, managing director of NetCollex, an adult entertainment company, offers two anecdotes that he thinks characterise the state of the industry’s decline. “One of the biggest licensed sex shops in Soho was Private in Brewer Street. It has recently become a coffee shop, which suggests people are more interested in coffee than they are in porn,” he says. “One of our clients had registered a domain called ‘wellhung.co.uk’. They were hoping to sell it for a lot of money to someone in the porn industry. In the end they sold it to a gallery in Shoreditch, which suggests there’s now more money in hanging pictures.”

The ‘YouPorn Guy’ speaks

It is curious how little mention is made of the object of their work – sex and women. The only time the word “sexy” is used is in relation to a technical development in e-billing services. Women are barely mentioned until midway through the keynote speech, given late in the afternoon, by a man who is known only by his initials JT, and branded as the “YouPorn Guy”. This veil of anonymity was adopted when he found himself the target of hatred and threats from pornography producers globally, because his site was disseminating free content, ripping apart the business model.

He is revered now by most in the industry, largely because he is one of the few people making money from porn, and the 60 or so delegates at the conference are gripped by his keynote presentation, which largely centres on his thoughts on the impact of the age-verification legislation and his recent decision to buy the domain “teen.xxx”. “I tried to explain to my kids why I am spending all their inheritance on buying up these domains,” he says, smiling at his son, who must be in his 20s and is in the audience listening. He is convinced that his grandchildren will benefit from this wise investment. “They will be saying ‘How did granddad know to buy that?’”

His speech is chatty and rich in preening stories about his humble career beginnings making dog kennels and competing with Teletext to set up a travel agency service. Since selling his share in YouPorn, he has turned to making adult clips, filmed mainly in the Czech Republic (“There are a lot of really lovely looking ladies in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, and there’s none of the stigma that we have here.”)

One of his most successful lines is a series of films about a taxi driver who persuades his female passengers to have sex with him in the back of his cab – a theme which, in the wake of the prosecution of taxi driver John Worboys, found guilty of raping or sexually assaulting 12 women, has triggered profound unhappiness from both the anti-porn campaign group Object and from Unite, the union that represents taxi drivers, which describes the series as “extremely distressing, demeaning to women and disrespectful to the thousands of taxi drivers in this country who are respectable people”. The site was nominated for a prize at Friday’s industry award ceremony.

‘We have to say to the girls: “I’m sorry”’

With practised self-deprecation, JT, who is now based offshore, tells the rapt audience that his career as a successful pornographer has its headaches just like any other job.

“Every two or three weeks we get a call from one of our performers, mainly in the Czech Republic, asking us to remove something. They say ‘My boyfriend will split up with me’ or ‘He has taken my baby away’. Some of them are really, really distressed. It is a horrible part … it is an upsetting part [of the job]. There is nothing we can do. The girls wanted to shoot, we pay them a lot of money … ” he says, flatly.

“We tell them it is going on the internet. We don’t pretend it is for our own consumption. But once a video is on the internet, there is nothing we can do. We have to say to the girls: ‘I’m sorry’. They say: ‘I’ll pay you.’ But there is nothing we can do.”

Women in the Czech Republic are paid €400 (£314) for a four-hour filming session, he says. Within 24 hours, the more popular clips can generate a million hits. He doesn’t reveal how much revenue this generates for his business.

“They don’t anticipate that their circumstances are going to change, and they shouldn’t have been in an adult movie,” he says. It is a fleeting moment, the only insight into the human cost of the industry throughout the day, before the speech moves quickly on to other subjects, such as the difficulty of getting mainstream advertisers interested in advertising on adult sites and whether virtual reality porn is going to be the next big thing (“I doubt it”, he says).

If pressed, delegates like to argue that women are the power players in the porn industry, equivalent to football stars, well-paid and able to create global brands. But this cheerful characterisation is dismissed by Roz Hardie, chief executive of Object, who points to one site, whose owner is at the conference, based on the theme of exploited African immigrant women. “We don’t believe those women are well-paid. Industry representatives try to present themselves as no more saucy than a Carry On film, but it’s a very superficial gloss. Some of these sites are very disturbing.”

Everyone here is anxious to analyse the impact of new UK regulations that require owners of sites to conduct an age-verification check before allowing browsers to access hardcore material. There is considerable bitterness from the audience, because this has been the death knell for the already struggling industry. Age verification costs the website provider around £1.50 a visit, and disc ourages a large proportion of browsers. Since sites based outside the UK don’t require it, people simply hop to another international site.

‘Regulation is a total mess’

Panellists make a great show of being in favour of the regulations in principle, but worry about the expense of it. “I hate the idea of my seven-year-old daughter seeing something that is not appropriate. But the costs might be prohibitively expensive,” a panellist tells the room. (I lose count of the number of people who tell me that they are fathers, and fear the effect pornography might have on their young children).

“I think age verification is a good thing – I don’t want kids to be accessing hardcore porn and I want to make money. We have to demonstrate that we take child protection seriously,” another says. Everyone expresses frustration that they are not operating on a level playing field, and argues that the regulations are not effective, because they only cover a small section of the available material.

“Twitter always amazes me. There’s porn on there that makes your hair stand on end,” a delegate says, asking why this site isn’t covered by the same regulations.

“Most political parties use the protection-of-minors issue as a sales pitch, drumming up votes, but actually they are doing very little to protect minors. The biggest sites accessed by people in the UK are international. Why doesn’t the government take those sites down? It isn’t the UK industry that has provided the increased access to internet porn. It is international,” Jamie, from Studio 66 TV, says. “We see the benefits of regulation in the industry, but it’s a total mess. You have the UK business suffering from over-regulation. Webcams, television, online, film, all regulated by different regulators, it’s crazy, it’s such a mess. It’s embarrassing. They are not doing anything to protect children. We need to come together as a group, and fight these battles as an industry.”

He asks that his surname shouldn’t be published because: “I have three kids, and not a lot of my kids’ friends know that I do this.

“I think people would perceive me in a different way – you have no respect for women, you must be a philanderer, you must be interested in sex. There is a misconception that women are enslaved by the adult industry,” he says. It turns out that many men in the adult industry are strangely prudish when it comes to Page 3, and the music videos of Beyoncé and Rihanna. “No one wants children to get access to porn. Most of them are parents. Just because you work in the adult industry doesn’t mean you’re not a parent,” he says, but it’s the more freely available content that worries him. “The music business poses much more of a threat to my daughter than the porn industry – Miley Cyrus, with Wrecking Ball.”

The industry-funded Association of Sites Advocating Child Protection (ASACP) is there, represented by Vince Charlton, whose day job is in the adult business (although he declines to say which part), but who takes on this role pro bono, wearing a branded ASACP T-shirt, that makes him look a bit like an NSPCC representative. “We are promoting the industry as responsible, taking child protection seriously; we’re not all dirty old men in raincoats, peddling 13-year-old Romanians,” he says.

But I’m confused by the willingness to embrace child protection and the industry’s parallel enduring interest in sites branded “hot teens”. Charlton says, with apparent sympathy, that it can sometimes be hard for content producers who “are inadvertently duped by the age of a girl, thought she was 19 but actually 17. You get a lot of people who falsify their identity for the purpose of earning a living.

“I personally don’t agree with a site that shows a 21-year-old dressed in school uniform with a lollipop in her mouth. It’s a personal thing, but it encourages you to see underage girls as sexual objects. I’m a father,” he says. “There used to be a lot more teens content. Now there is more of a moral backlash against the idea. There are a lot of people in the industry who are fathers, who find it distasteful. But it’s not against the law.”

‘The content that users want to watch’

JT, the keynote speaker, is semi-apologetic about his excitement over his purchase of the teen.xxx site, when I ask him as he leaves the conference. “I create the content that users want to watch. Teen unfortunately is one of the most searched for terms … Unfortunately because it can be portrayed as underage porn,” he says, adding that all his performers are over 18. “I just want to shoot really good content. It is unfortunate, but I just want to make good, complimentary content.”

Predictably, all the speakers at the conference are men, although there are a handful of women in the audience. The delegates appear to split into two groups. There are corporate executives in suits, people such as Mitch Farber, from NETbilling “the largest payment gateway, merchant account acquirer and call centre provider in the adult space”, who are making money from back-office services to the industry, profiting from the fact that the more mainstream companies won’t process porn payments. And there are people who are in the industry partly because they hope to make money, but actually because they really like porn.

Ben Yates, a graphic designer who is hoping to make a living from producing porn films, comes into the second category. He scrapes together about £1,200-£1,300 a month from selling his films, not enough to abandon his day job. “I can’t make a living from it at the moment – not with piracy, regulation, overheads. It’s in a bad state,” he says. “But I like the industry. It’s corny to say, but there are great people, and I like the creative aspects of the business.”

At the annual industry awards, in a warehouse space in west London that evening, it’s obvious that this is a business that isn’t thriving financially. “It’s not exactly the Oscars,” one of the organisers says apologetically, as presenters get tangled up in their microphone wires, and the audience is deafened by scratchy feedback. It’s more Pontins than LA.

Clips of work by female performers are projected on to a screen, as nominations for the best female artist and best newcomer are read out. Fully clothed industry men (and they are almost entirely men) in suits or jeans and T-shirts that declare things like “I Love Gutter Sluts” are joined by women, most of whom aren’t wearing as much. The female presenter congratulates each nominee with peculiar approval: “Ahh! You’re so filthy, you slut!” or “Come on you old slag!”

Charlton, from ASACP, is there with friends. “The girls are having a lot of fun,” he says, a little defensively. “As long as they don’t hurt the children.”

Kiki Minaj, one of the nominees, who says she switched to adult modelling from accountancy two years ago, has noticed a decline in the amount of work available, even in that timeframe. “When I started I was being booked for filming three or four times a week, now it’s once a week if you’re lucky,” she says. She has had to become more open-minded about what she is prepared to do. “If you don’t do special stuff, you get someone from Poland who will come and do it for half the price. It’s just like construction.”

The event leaves even some in the industry feeling a bit depressed. “Most people who get into the adult industry don’t choose to get into it; they fall into it,” an adult TV company director says. “I didn’t want to work in the adult industry. I would walk away tomorrow, between you and me. It is a bit boring.”