Walmart is known for cutting its prices to elbow rivals. Now it appears that Amazon is beating the giant retailer at its own game.

Amazon keeps elbowing rivals like Walmart, Target and Kmart by cutting prices on the kind of products most Americans like to keep stocked at home. Not everyone may buy LCD TV screens – electronics are still the company’s biggest moneymaker – but everyone buys toilet paper. So Amazon has aggressively pushed down the online prices of consumer goods such as groceries, home care, pet supplies and personal care products, Bernstein Research analysts found. Amazon’s online price cuts appeared to undercut its land-based competitors, said the Bernstein analysts: “we believe [Amazon] are doing so more extensively than in offline retail.”

Price cuts, are, of course, Amazon’s strategy, and one it’s learned from Walmart. But the deep cuts are slicing into the company’s margins – and its profitability. It’s also likely trimming Amazon’s stock price, which peaked at $408 in January, and has dropped to $326.

Amazon just doesn’t seem to care.

In Amazon’s Q3 earnings call last month, chief financial officer Tom Szkutak fielded tough questions from analysts after announcing the company had an operating loss of $437m.

Aram Rubinson, an analyst from Wolfe Research asked Szkutak exactly what financial measures were important to Amazon, “because it’s a little hard to see any of it making positive progress, so I just – I’d love to get back to basics,” he said.

Szkuktak agreed that Amazon had been in “investment mode” for the last few years – a generous understatement for a company whose bottom line has been in the red for most of two decades. “We don’t focus on individual margins,” he reiterated to analysts, conceding that Amazon wanted to maximize its free cash flow.

Benedict Evans, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, has joked on his blog that Amazon, while deferring profits to investors, may be the world’s largest lifestyle business.

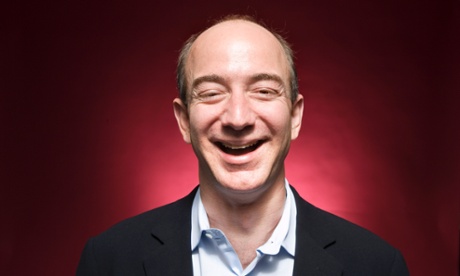

In a post titled Why Amazon Has No Profits (And Why It Works), Evans writes of the company: “Bezos is running it for fun, not to deliver economic returns to shareholders, at least not any time soon.”

The price cuts are a way for Amazon to shoulder its way into a business – consumer goods – that is relatively new. Until recently, household goods have dominated at traditional supermarkets or stores at suburban strip malls.

To get those customers, Amazon has set itself up to take on Walmart and draw people into online shopping who normally would not consider buying household products outside a store.

These new numbers, according to Bernstein analysts, confirms Amazon’s bolstering of their newest offerings – Amazon Fresh and Amazon Pantry. “If Amazon would have anything to do with it, they’d like Walmart gone completely,” says Doug Stephens, a retail consultant who describes himself as a “retail futurist” and advises companies such as Citibank and Target.

With Amazon Fresh, they anticipate, Stephens says, that a large portion of Americans are going to be too old to drive in the next few decades, pegging the number at 80 million. Those aged between 44 and 65 make up 26.4% of the US population, and are an attractive demographic for Amazon, if it has home delivery of grocery to offer.

Surprisingly, in spite of Amazon’s obvious intentions, it was Walmart that started this price war. On 13 November, Walmart announced the Ad Price Match guarantee, declaring it would match any online retailers, including third-party sellers on Amazon.

A Wells Fargo/360pi retail study examined how all the major retailers stacked up. Researchers combed 100,000 products sold at Amazon, Target, Walmart, Kohl’s, Macy’s, Sears, Best Buy, RadioShack, Lowes and Home Depot.

The result: there is a big three of retail price-cutters. Amazon had the lowest prices of any retailers except Walmart and Target.

This pricing arms race can only result in mutual capitalist destruction, experts suggest. Walmart will likely be unable to keep up, experts suggest. How can you operate over 4,000 stores in the US, with 300 employees per store, and maintain all of that while competing at modest online prices, Stephens wonders? “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Amazon may also get the benefit of a generational shift in online retail. A large portion of Americans growing too old to drive to the store and younger shoppers too bored to go into stores leaves Amazon in a peachy position.

Gen Y and millennials, on the other hand, do not share older users’ reservations about shopping online. In fact, they like it quite a lot, as long as it’s for interesting goods. Studies reveal that 50% of young male shoppers and 70% of female shoppers see shopping as entertainment.

It’s an approach that there is nothing wrong with, according to Evans of Andreessen Horowitz. He writes “profit is opinion but cash is fact”. He points at Bezos’ famous paper-napkin diagram for Amazon, their classic idea of injecting their revenue into further expansion.

This increased and never-ending re-investing back into the company makes sense, per Evans, because, well, Amazon has barely captured only 1% of the US retail market. Why stop now?

Share prices tumbled by 13% after Amazon’s earnings missing estimates and poor sales projections for the holiday period. Even in spite of a 20% climb in revenue from Q3 in the previous year, Amazon may be losing its sheen. “There isn’t the zeal that you might have found years ago for amazon’s continual loss of profitability,” says Stephens.