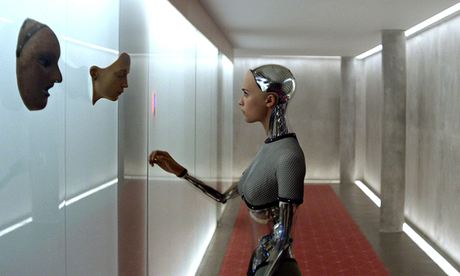

From 2001: A Space Odyssey to Blade Runner and RoboCop to The Matrix, how humans deal with the artifical intelligence they have created has proved a fertile dystopian territory for film-makers. More recently Spike Jonze’s Her and Alex Garland’s forthcoming Ex Machina explore what it might be like to have AI creations living among us and, as Alan Turing’s famous test foregrounded, how tricky it might be to tell the flesh and blood from the chips and code.

These concerns are even troubling some of Silicon Valley’s biggest names: last month Telsa’s Elon Musk described AI as mankind’s “biggest existential threat… we need to be very careful”. What many of us don’t realise is that AI isn’t some far-off technology that only exists in film-maker’s imaginations and computer scientist’s labs. Many of our smartphones employ rudimentary AI techniques to translate languages or answer our queries, while video games employ AI to generate complex, ever-changing gaming scenarios. And so long as Silicon Valley companies such as Google and Facebook continue to acquire AI firms and hire AI experts, AI’s IQ will continue to rise…

Isn’t AI a Steven Spielberg movie?

No arguments there, but the term, which stands for “artificial intelligence”, has a more storied history than Spielberg and Kubrick’s 2001 film. The concept of artificial intelligence goes back to the birth of computing: in 1950, just 14 years after defining the concept of a general-purpose computer, Alan Turing asked “Can machines think?”

It’s something that is still at the front of our minds 64 years later, most recently becoming the core of Alex Garland’s new film, Ex Machina, which sees a young man asked to assess the humanity of a beautiful android. The concept is not a million miles removed from that set out in Turing’s 1950 paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, in which he laid out a proposal for the “imitation game” – what we now know as the Turing test. Hook a computer up to text terminal and let it have conversations with a human interrogator, while a real person does the same. The heart of the test is whether, when you ask the interrogator to guess which is the human, “the interrogator [will] decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman”.

Turing said that asking whether machines could pass the imitation game is more useful than the vague and philosophically unclear question of whether or not they “think”. “The original question… I believe to be too meaningless to deserve discussion.” Nonetheless, he thought that by the year 2000, “the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted”.

In terms of natural language, he wasn’t far off. Today, it is not uncommon to hear people talking about their computers being “confused”, or taking a long time to do something because they’re “thinking about it”. But even if we are stricter about what counts as a thinking machine, it’s closer to reality than many people think.

So AI exists already?

It depends. We are still nowhere near to passing Turing’s imitation game, despite reports to the contrary. In June, a chatbot called Eugene Goostman successfully fooled a third of judges in a mock Turing test held in London into thinking it was human. But rather than being able to think, Eugene relied on a clever gimmick and a host of tricks. By pretending to be a 13-year-old boy who spoke English as a second language, the machine explained away its many incoherencies, and with a smattering of crude humour and offensive remarks, managed to redirect the conversation when unable to give a straight answer.

The most immediate use of AI tech is natural language processing: working out what we mean when we say or write a command in colloquial language. For something that babies begin to do before they can even walk, it’s an astonishingly hard task. Consider the phrase beloved of AI researchers – “time flies like an arrow, fruit flies like a banana”. Breaking the sentence down into its constituent parts confuses even native English speakers, let alone an algorithm.

Is all AI concerned with conversations?

Not at all. In fact, one of the most common uses of the phrase has little to do with speech at all. Some readers will know the initials AI not from science fiction or Alan Turing, but from video games, where it is used to refer to computer-controlled opponents.

In a first-person shooter, for example, the AI controls the movements of the enemies, making them dodge, aim and shoot at you in challenging ways. In a racing game, the AI might control the rival cars. As a showcase for the capabilities of AI, video games leave a lot to be desired. But there are diamonds in the rough, where the simplistic rules of the systems combine to make something that appears complex.

Take Grand Theft Auto V, where the creation of a city of individuals living their own lives means that it’s possible to turn a corner and find a fire crew in south central LA having a fist-fight with a driver who got in the way of their hose; or Dwarf Fortress, where caves full of dwarves live whole lives, richly textured and algorithmically detailed. Those emergent gameplay systems show a radically different way that AI can develop, aimed not at fully mimicking a human, but at developing a “good enough” heuristic that turns into something altogether different when scaled up enough.

So is everyone ploughing money into AI research to make better games?

No. A lot of AI funding comes from firms such as Apple and Google, which are trying to make their “virtual personal assistants”, such as Siri and Google Now, live up to the name.

It sounds a step removed from the sci-fi visions of Turing, but the voice-controlled services are actually having to do almost all the same heavy lifting that a real person does. They need to listen to and understand the spoken word, determine how what they have heard applies to the data they hold, and then return a result, also in conversational speech. They may not be trying to fool us into thinking they’re people, but they aren’t far off. Because all the calculations are done in the cloud, the more they hear, the better they are at understanding.

However the leading AI research isn’t just aimed at replicating human understanding of the world, but at exceeding it. IBM’s Watson is best known as the computer that won US gameshow Jeopardy! in 2011, harnessing its understanding of natural language to parse the show’s obtuse questions phrased as answers. But as well as natural language understanding, Watson also has the ability to read and comprehend huge bodies of unstructured data rapidly. In the course of the Jeopardy! taping, that included more than 200 million pages of content, including the full text of Wikipedia. But the real goal for Watson is to expand that to full access to the entire internet, as well as specialist data about the medical fields it will eventually be put to work in. And then there are the researchers who are just trying to save humanity.

Oh God, we’re all going to die?

Maybe. The fear is that, once a sufficiently general-purpose AI such as Watson has been created, its capacity will simply scale with the processing power available to it. Moore’s law predicts that processing power doubles every 24 months, so it’s only a matter of time before an AI becomes smarter than its creators – able to build an even faster AI, leading to a runaway growth in cognitive capacity.

But what does a superintelligent AI actually do with all that capacity? That depends on its programming. The problem is that it’s hard to program a supremely intelligent computer in a way that will ensure it won’t just accidentally wipe out humanity.

Suppose you’ve set your AI the task of making paperclips and of making itself as good at making paperclips as possible. Pretty soon, it’s exhausted the improvements to paperclip production it can make by improving its production line. What does it do next?

“One thing it would do is make sure that humans didn’t switch it off, because then there would be fewer paperclips,” explains Nick Bostrom in Salon magazine. Bostrom’s book, Superintelligence, has won praise from fans such as SpaceX CEO Elon Musk for clearly stating the hypothetical dangers of AI.

The paperclip AI, Bostrom says, “might get rid of humans right away, because they could pose a threat. Also, you would want as many resources as possible, because they could be used to make paperclips. Like, for example, the atoms in human bodies.”

How do you fight such an AI?

The only way that would work, according to some AI theorists such as Ray Kurzweil, a director of engineering at Google, is to beat it to the punch. Not only do humans have to try to build a smart AI before they make one accidentally, but they have to think about ethics first – and then program that into it.

After all, coding anything simpler is asking for trouble. A machine with instructions to “make people happy”, for example, might just decide to do the job with electrodes in brains; so only by addressing one of the greatest problems in philosophy can we be sure we’ll have a machine that understands what it means to be “good”.

So, all we have to do is program in ethics and we’ll be fine?

Well, not quite. Even if we manage to not get wiped out by malicious AI, there’s still the issue of how society adapts to the increasing capability of artificial intelligence.

The Industrial Revolution was characterised by the automation of a number of jobs that previously relied on manual labour. There is little doubt that it represented one of the greatest increases in human welfare ever seen. But the upheaval at the time was momentous and something we could be about to see again.

What steam power did for physical labour, AI could do for mental labour. Already, the first casualties are starting to become clear: the minicab dispatch office has little place in a world of Hailo and Uber; the job of a stockbroker has changed beyond all recognition thanks to the introduction of high-frequency trading; and ever since the construction of the Docklands Light Railway in the 1980s, the writing has been on the wall for train drivers.

And the real changes are only just beginning. In November, Goldman Sachs led a $15m funding round for Kensho, a financial data service that uses AI techniques to pump out financial analysis at a rate no human analyst could match. And it can do it while taking stock of the entirety of the huge amount of financial data available, something humans simply can’t cope with.

Kensho’s analytical notes could then be passed on to a high-frequency trading firm such as Athena, which will use the insights to gain an edge of milliseconds on the market – that’s enough to make money, if you’re trading with billions of dollars. Once the trading has affected the market, it might be written up for Forbes by Narrative Science, which uses algorithms to replace financial journalists. After all, most business stories follow a common template, and the data is already available in a structured format, so why waste time getting people involved at all?

On aggregate level, these changes are a good thing. If the work of millions of people is covered by algorithms, then output goes up, hours worked go down, and we move one step closer to a Jetsons-style utopia.

In the end, it will be OK?

Assuming we avoid the superintelligent AIs wiping us out as an afterthought, manage to automate a large proportion of our jobs without creating mass unemployment and societal unrest, and navigate the tricky boundaries of what personhood entails in a world where we can code passable simulacra of humans, then yes, it should be fine.