Aspiring superheroes may soon be able to climb like Spider-Man thanks to scientists working with the US military who have developed a material which enables a human to ascend a vertical glass wall.

The researchers, inspired by the sticky toes of geckos, created hand-sized silicone pads covered with tiny ridges that are capable of adhering to smooth surfaces.

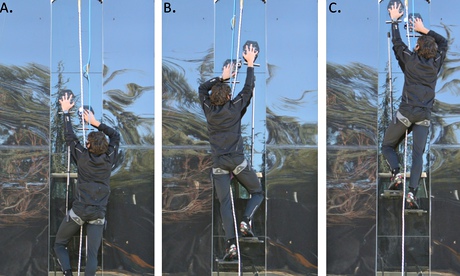

They then built a harness with each hand pad supporting the weight of a foot rest, to which it is connected by a pole.

The pads feature rows of microscopic slanting wedges that temporarily bond to the surface of the glass when weight is applied.

Previous attempts to copy gecko feet failed but scientists at Stanford University, working with the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), found a way of sharing the load between 24 postage-stamp sized tiles on each pad.

This allowed researcher Elliot Hawkes, a biomimetics student at Stanford, who weighs 11 stone, to climb a 3.5 metre tall vertical glass wall.

They now hope to develop the technology to allow climbers to move faster and more smoothly.

It could eventually lead to gloves similar to those used by Tom Cruise’s character in the film Mission Impossible – Ghost Protocol to climb up the outside of the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Prof Mark Cutkosky, a biomimetic engineer at Stanford University who led the research, said of past efforts: “Unfortunately ‘spider suits’ ignore some basic ergonomic issues. People have much greater strength in their legs than in their arms.

“Therefore we think one needs a system where the hands are used to gently attach and detach the adhesive tiles. A system of cables and links transfers the load to the feet.”

The researchers developed the adhesive pads, which are not sticky and can be repeatedly reused, as part of the Darpa Z Man project – aimed at helping soldiers scale buildings and other obstacles more easily.

They made the breakthrough after studying the way the Tokay gecko, a native of Asia, climbs. Their results are published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface on Wednesday.

Geckos use tiny bristles on their toes called setae, each of which is split into nano-sized tips called septulae. Weak electrical interactions between the molecules in septulae and the surface they are walking on provide grip that allows geckos to even climb upside down.

Cutkosky and his colleagues developed adhesive pads from a silicone material called polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) that is moulded into microscopic slanted wedges.

These grip the smooth surfaces, including glass, plastic, wood and painted metal, in a similar way to the gecko’s feet when they have a load pulling against the tips of the wedges. The adhesive pads can be removed by lifting the weight from the pads.

Hawkes found that by using small tiles meant the pads could conform to a surface more easily than a single adhesive surface.

He also found that sharing the load through a system of “tendons” and springs allowed the pads to support adult human weight – and even outperform geckos themselves.

Cutkosky said: “As the load increases, the tendons and springs ensure that all tiles converge to the same maximum load.

“Without this provision, one tile somewhere in the array will become overloaded and will fail. Then its neighbours will fail and so on. The failure proceeds like an avalanche across the entire array.”

However, on rough surfaces the microwedge material does not perform well. Hawkes believes this could be overcome by using smaller tiles or adhesive materials better suited to rough terrain.

He said: “The synthetic adhesion system may be able to outperform a gecko on relatively flat, smooth and clean vertical glass, on other surfaces, it has poor performance compared with the gecko.

“To adhere to surfaces with more curvature, the tile size could be decreased at the expense of greater system complexity and for rougher surfaces, the adhesion system could be outfitted with one of the gecko-inspired adhesive materials that have been developed for use on these surfaces.

“On contaminated surfaces, even geckos have trouble producing adhesion. The PDMS microwedge adhesive can be cleaned between steps by touching a material of higher surface energy like sticky tape and it may be possible to achieve self-cleaning.”

The researchers believe their suit could find other uses beyond climbing and are also working with Nasa to develop ways to help grasp space debris. Cutkosky said: “Controllable dry adhesives are one of very few technologies that will work in space – they don’t require suction, they work at low temperatures and they don’t require external power.”