Nobody does gay zombie porn quite like Bruce LaBruce.

With a touch of camp, a splash of wit and buckets of fake blood, the Toronto-based film director has been making brilliantly bizarre independent films for the past 30 years. A wild child sibling of John Waters and Kenneth Anger, LaBruce steps into the spotlight for a film retrospective that opens with his intergenerational romcom Gerontophilia on Thursday night.

The retrospective covers everything from his early days of no-budget ad hoc porn to million-dollar-budget features and Sundance premieres. All nine of his features screen alongside a program of shorts that track his footprints through horror porn, the punk avant-garde and gay art underground, including characters ranging from romantic skinheads to zombies with freaky alien genitals.

LaBruce started out in the 1980s splicing Super 8 film strips in the editing room, “doing it very old school”, he recalls, while on the forefront of the lo-fi, punk cultural movement “queercore”, which offered an anarchistic alternative to traditional gay cinema.

Queer cinema is becoming mainstream. This retrospective is a throwback to the movement’s pre-internet, punk roots. It also shows LaBruce’s knack for twisting film genres into new territory. His work could be considered high-art porn with a plot, mixed with taboos and intellectual drama to satiate the most cerebral, neurotic audience.

On a Skype call from Canada, the film pioneer talks through his feature films.

No Skin Off My Ass, 1991

Called a “homocore classic”, LaBruce stars as a hairdresser who falls for his then-boyfriend, a hot punk skinhead with muscles. He performed his first on-camera sex scene. “I approached it in a very naïve way,” says LaBruce. “Our friend Candy was behind the camera but we couldn’t do it with her in the room. She’s one of my best friends, I was so self-conscious.” They put the Super 8 camera on running lock, so it ran by itself.

Super 8½, 1994

This semi-autobiographical tale follows an avant-garde film-maker who faces a fading film career. A fringe arthouse masterpiece, it is laden with humour and film references, like drawing a parallel to Marcello Mastroiannin in Fellini’s 8 ½. It stars the New York portrait photographer Richard Kern and the intersex performance artist Vaginal Davis, and LaBruce as (almost) himself. “I’ve never lost sight or betrayed my roots,” says LaBruce.

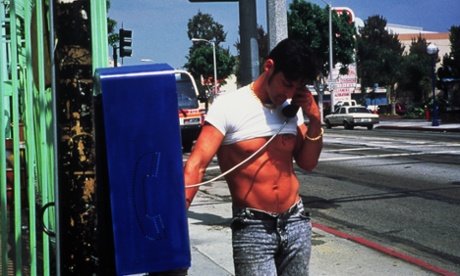

Hustler White, 1996

Shot on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood, this black comedy is a critique of the porn industry. The story follows LaBruce, who acts as a writer investigating sex workers in California. The film is riddled with nods to old Hollywood, and real hustlers were cast for the film. This is also is the last film the director stars in. “I didn’t want to be an actor,” LaBruce recalls. “I only acted because I knew I would show up and I wouldn’t have to pay myself. After Hustler White, I retired from the idea of being an actor. It’s not who I am.”

Skin Flick, 1999

Shot in London, this film follows a neo-Nazi gang of skinhead thugs who gay bash and rob their way through life. While the men are gay (it was produced for Cazzo, an adult film studio), they are also homophobic. One of the most controversial scenes of the film – and LaBruce’s career – is the gang rape of an interracial couple. “When it played in London, it was the first time I had picketers outside one of my films,” said LaBruce, who was called a racist. “A few times, I went too far, coping with the consequences of what I did or questioning my own work. That was always a good sign because I not only pushed the boundaries but pushed myself into an uncomfortable place.”

The Raspberry Reich, 2004

Twisted, leftist radicals prove their devotion to an underground political movement by making porn propaganda. Part-comedy (obviously), this “terrorist chic” film was shot in Berlin. “The revolution is my boyfriend” slogan has made this work a cult masterpiece, which was funded by Cazzo, meaning there was both a hardcore and a softcore version. LaBruce said making “real” porn is “not as glamorous as people think”, he said. “You end up with a scene that seems flawless but it’s an illusion, you don’t shoot in sequence, you have to reshoot certain things, you extend moments through editing. It’s show business, altogether.”

Otto; or Up with Dead People, 2008

Shot in some of the most beautiful parts of Berlin, a gay emo zombie stumbles through an existential crisis. “It was one of the first gay zombie films with a sympathetic character, a sensitive zombie with a hoodie,” said LaBruce. One scene has Otto and another zombie having sex through an open wound – at its Sundance premiere, roughly 50 people walked out from a theatre of 700. “In retrospect, I could have made a film that wasn’t sexually explicit.”

LA Zombie, 2010

Probably his most gruesome zombie porn flick, this film follows an alien zombie who brings dead bodies back to life through intercourse. Banned in Australia, it drenched the silver screen red. “I tried using real meat in LA Zombie; it was a disaster, it didn’t splatter right,” said LaBruce. “I’ve had various recipes for fake blood, it’s very tricky to make it real. With gore you get inventive. Art directors love it.”

Gerontophilia, 2013

The retrospective opens with this romcom between a young retirement home worker and an elderly patient. LaBruce’s most successful film to date, it had a budget of over $1m. He “wanted to shock people by making a film that isn’t shocking”, so avoided sex scenes altogether. The topic is still taboo but caters to the mainstream. “It’s really my first feature where there wasn’t explicit sex in it, which is kind of crazy,” he said. “I was expecting more blowback from my hardcore fans, who expected something shocking or pornographic. There wasn’t that, weirdly.”

Pierrot Lunaire, 2014

This adaptation of Austrian theatre director Arnold Schoenberg’s masterpiece adds a transgendered twist – German actor Susanne Sachsse stars as Pierrot Lunaire. An opera with dildos, it captures the spirit of LaBruce’s earlier years, when he said his treatment of homosexuality was a response against liberal tolerance. “As long as you don’t flaunt it or push it in people’s faces – that pushed me even more to push it in people’s faces,” he said. “Make it ambiguous, scary or romantic, but certainly aggressive. That set the stage for a lot of my work.”

- The Bruce LaBruce film retrospective runs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from 23 April to 2 May. Details here