One rainy Friday in October, Steve Coogan takes a trip from the Lake District to an expensive part of London. He rolls into town a man in transit, still half-dressed for the country with a yellow tweed cap pulled down round his ears. The car ferries us through sodden streets to a private members club, where a table is booked in an upstairs room. But the hostess is stricken; the place has standards. She won't let him in until he takes off the cap.

It's fitting that Coogan doesn't pass for clubhouse material. His stock in trade is the comedy of embarrassment, the bumbling social faux pas: he has built his success on the concept of failure. And Coogan himself often seems barely a whisker away from the characters he plays, prone to the same cravings, the same failings. You can take the boy out of Manchester, but he might still wear his hat.

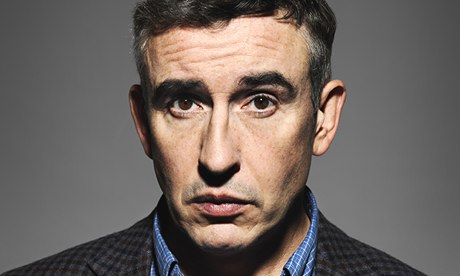

He pulls up a chair and orders some tea (English Breakfast, nothing fancy). He sits with his back to the wall, his collar turned up, his dark eyes darting. The club room is cosy but he will never fit in and the snub clearly rankles. "I'm northern lower middle class," he says by way of introduction. "And it's taken me 20 years in the business to realise that's an asset, not a handicap." He shrugs. "But I've still got a huge chip on my shoulder. Chips, peas, mushy peas. And a boat of gravy on the side."

He shouldn't need reassurance. At the age of 48, he is in the prime of life, his career going full tilt. This year he has played Paul Raymond in The Look Of Love, acted alongside Julianne Moore in a knotty adaptation of What Maisie Knew, and spun Alan Partridge into a successful feature-length outing.

His new film, Philomena, may well be his most rounded work to date – the role that might bury his lingering reputation as "just" a TV comedian. Meanwhile, off-screen, the one-time tabloid whipping boy has recast himself as an angel of vengeance, banging the drum for press reform and testifying at the Leveson inquiry into press ethics. His closet, he explains, has been emptied of skeletons. That gives him the freedom to say what he wants.

Coogan pours the tea and explains why Philomena is a passion project, one that really counts. Directed by Stephen Frears, it tells the story of Philomena Lee, a retired Irish nurse on a mission to find her adult son, sold to adoptive parents by nuns nearly 50 years before. Coogan read Lee's story online in 2009, he says, at a moment when he was casting about for a more weighty project; the story reduced him to tears.

"For a few years I'd been railing against postmodernism and irony," he explains. "I've got this real anger against people who think the best way of dealing with the world is through sardonic eyes. It's a depressing, defeatist view of humanity. And I wanted to do something that was sincere, that was not smart and clever for its own sake. I had this notion that the most radical, avant-garde thing I could do was to talk about love. There's nothing that will make an intellectual's buttocks clench more than to talk about love."

Philomena showcases a reliably winning turn from Judi Dench as the shop-worn Catholic heroine – a casualty of the Magdalene laundries, dogged in her pursuit of the child that was taken. Yet Coogan is the film's driving force, having signed on to produce and co-write the script, as well as give a deft, nuanced performance as Martin Sixsmith, the BBC reporter turned government spin doctor who was sacked, hit the road and found redemption. His Sixsmith is prickly and embattled, the latest in Coogan's long line of thwarted men. "Yeah, I put a lot of myself in there," Coogan admits. "He's half Martin and half me."

Coogan says he never intended the film as a comedy: the humour is there just to sweeten the pill. That said, it's not quite an attack on Catholicism, either. Yes, he's an atheist, because "agnosticism is for cowards". But his family still practises and he doesn't want to disrespect their beliefs. Besides, the older he gets, the more sympathy he has. Believing in God does not make you a fool. "I remember discovering the word 'duality' about 15 years ago. That it was OK to think two different things at the same time. It was a revelation to me, that you could take a holistic view of things and hold those tensions without it sending you mad."

When Philomena premiered at the Venice film festival last month, it won an award from a Catholic organisation and another from a secular organisation. He's proud of that fact: it shows he squared the circle. "Or if you want to be unkind, that I've offended no one and said absolutely nothing at all." He gives an awkward bark of laughter and reaches for his tea.

Coogan was raised in Middleton, on the northern outskirts of Manchester, the fourth of seven children and the "runt of the litter", according to his big sister Clare. His mum raised the kids while his dad worked as an IBM engineer. The family voted Labour every polling day and attended church each Sunday. "I'm actually glad I was raised a Catholic," he says. "It's informed my values and given me something to write about. I meet a lot of people who were raised in these vaguely liberal, hippyish, bohemian backgrounds and I think, 'Well, where's the tension?' Struggles inside your head, notions of sin and general dysfunction – it's all incredibly fruitful. Having that kind of moral framework enables me to object to the moral framework." He frowns. "It's a paradox."

By his early 20s he was already working on TV, providing the voices of Neil Kinnock and Margaret Thatcher on the Spitting Image puppet show. Taking to the standup circuit with his friend John Thomson, he won the 1992 Perrier award at the Edinburgh festival and landed a slot alongside Chris Morris and Armando Iannucci on Radio 4's satirical news show On The Hour. It was here that he would road test his most indelible comic creation: a chippy, Pringle-clad alter ego who is bound to dog his steps to the grave.

If anything, Alan Partridge has become more interesting to play, Coogan says, as the character has bounced from outside broadcasts to chat-show sofa to a poky studio at North Norfolk Digital, hosting irascible phone-ins and lauding Billie Piper as "the most popular prostitute on ITV". The two men have grown up together, united by their fascination with cars, women and the machinations of mainstream celebrity. Coogan points out that Partridge started out crude and one-dimensional, a blundering sports presenter who knew nothing about sport. Now there's more light and shade, more pathos. "There's more of me in him," he says. "Maybe the worst part of me. Every now and then these slightly Middle England, xenophobic, curtain-twitching Daily Mail thoughts will start creeping into my head. And the best way to exorcise those views is to channel them into Alan."

Is Partridge his canary in the mine? Coogan thinks this over. "In the early days, 20 years ago, I was part of two gangs. One was the Manchester gang: Henry Normal, Caroline Aherne, John Thomson and Craig Cash. There was this northern scene that felt very secure and comfortable for me. But then there was this other group, Armando Iannucci's gang. Patrick Marber, Rebecca Front and also Stewart Lee and Richard Herring. And I regarded them as very avant garde and Oxbridge and comically aspirant. They wanted to do things in a new way and I learned from that. I wanted what they had. And actually I had something they didn't have, the whole Manchester side. But yes," he says, "they educated me. I think they stopped me becoming Alan Partridge for real."

The central heating is running full blast and the club is a furnace. Coogan slips off his jacket and drops it to the floor. He does this furtively, as though braced for a quarrel. "I think Charles Dickens used to come here," he says in a murmur. "And I suppose they think they can recapture a flavour of Dickensian London by insisting people wear jackets and take off their hats. It really irritates me, stuff like that."

At the turn of the century, Coogan cashed in his chips and lit out for Hollywood, following in the footsteps of his hero Peter Sellers. He played Phileas Fogg in Around The World In 80 Days, a Roman general in Night At The Museum and a corporate cupid in The Alibi, which went straight to DVD. The experience left him feeling hollow and embarrassed, and these days he accepts that the decision was wrong. "I went to America and did mediocre parts in mediocre films," he shrugs. "I never did it because I wanted to. I did it because I was told that this is what I was supposed to do. And I didn't feel comfortable. I felt like a dick."

Back in England, he tried out for various dramas but hit a wall of rejection. The low point came when he auditioned for an ITV series ("not even a particularly memorable one") and two executives took him aside to explain that his specialty was "comedy caricatures", not the serious stuff. "That pissed me off so much. It made me realise that if it was going to happen, I'd have to do it myself."

Had he come to see comedy as a creative cul-de-sac? "Yes, I think it can be. I got very bored with clever, cynical comedy. I've done some of it and I enjoy some of it. But eventually you want some nourishment. It's like getting pissed and doing coke. It's fun but it doesn't really nourish you." He laughs. "It's not a good balanced diet with all the food groups and a little protein. And as I get older I think, 'What contribution am I making? How am I adding to the sum total of human happiness?' " My God, he really asks himself those questions? "Well, not every morning," he says, deadpan. "In the morning I want some coffee and some blueberries and some nuts on my granola."

By and large Coogan likes upending his critics. He was filed as an impressionist until he won the Perrier; he was shackled to Partridge until he bounded into movies, giving a delicious turn as indie impresario Tony Wilson in 2002's supple 24 Hour Party People. "In a curmudgeonly way I like the idea of people sharpening their knives and then having to put them back in the knife draw. What's the opposite of schadenfreude? When you want something to be shit and then have to admit that it's good?"

Coogan divides his time between a house by Coniston Water and another outside Brighton. He bought the first in order to have a base near his extended family, and the second to be close to his daughter, who is 16 and lives with her mother. His current partner, 23-year-old Elle Basey, is a lingerie model he met while guest-editing an issue of Loaded magazine. He was dressed as Partridge and she was in her pants.

Coogan has always insisted that his private life should stay private, which is all well and good. And yet his situation is complicated by the tension between himself and his characters. He likes testing the elastic between fiction and autobiography to see how far it will stretch. In the BBC series The Trip, Coogan plays "Steve Coogan", vain and thin-skinned and horny as hell. He comes gliding through Cumbria in a shiny black Range Rover, chatting up waitresses, bickering with "Rob Brydon" (played by Rob Brydon) and complaining that the world won't take him seriously; that Michael Sheen snaffles the roles that should rightfully be his. Isn't playing himself a dangerous game, inviting a conversation he would rather not have?

No, says Coogan. "I'm playing with the image, but that's my prerogative. If I want to take something traumatic that happened in my childhood and put it in my work, that's my choice. That doesn't mean that all bets are off. That doesn't mean that everyone else can start talking about it." He sighs. "Besides which, when I do The Trip there's still a line that we draw. I have actors playing my parents, actors playing my girlfriends. I have a son in the show and I don't have a son. And I do all these things deliberately."

In the past, the public Coogan has found himself bedevilled by the private Coogan. The Daily Mail (the paper he loathes above all others) dubbed him "Coogan the Barbarian" and insinuated that his hell-raising antics had nudged the Hollywood star Owen Wilson, a friend, to the brink of a breakdown. The red-tops, meanwhile, revelled in reports of cocaine use, liaisons with lap-dancers and an extended sex session on a bed full of banknotes. He concedes that much of this had some basis in fact, but that's not the point. He never courted the tabloids and resented being installed there. "Fame is a byproduct of what I do, it's not the be-all and end-all. I never signed that Faustian pact."

Is this strictly true? The impression I have of the younger Coogan is of someone half-drunk on acclaim; in and out of strip clubs, in and out of rehab.

"OK, yeah," says Coogan. "First of all, I would say it's still none of your business. If I choose to go to a strip club, it's still none of your fucking business. There are people who seek fame as an end in itself. I'm not one of those people."

The term celebrity is demeaning, he argues – he's no more of a celebrity than Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre or the Guardian's Alan Rusbridger. Sure, he has had people go through his dustbin and been the subject of an attempted News Of The World sting by Andy Coulson. "But beyond all that is the notion of monstering innocent victims, people like the parents of Milly Dowler or Chris Jefferies in Bristol, people who never signed up to be in the public eye."

In August 2011, Coogan's legal team obtained evidence that his phone had been hacked on behalf of the News Of The World. He went on to testify at the Leveson inquiry and, with Hugh Grant, became the public face of the Hacked Off campaign. Today he has contempt for anyone who holds out against press regulation; who attempts to reduce the whole argument to a simple issue of freedom of the press. And he has contempt for tabloid hacks who pass themselves off as torch-bearers for truth. He's not overly enamoured of his fellow travellers, either, most of them too nervous to wade into battle. "It was me and Hugh Grant: everyone else was too petrified. All those spineless celebrities, so worried about annoying that cunt Paul Dacre." He shrugs. "What the fuck is wrong with them?"

The way Coogan tells it, his history with the press has built up his immunity. But the experience appears to have made him curiously sensitive as well. I'm not sure I've ever met a non-journalist so attuned to the way the press works, or so fascinated with modern media parlance. On the one hand, he doesn't want this interview to pander to the tabloid take on what he's like behind closed doors. On the other, he doesn't want to be cast as a bad-boy-made-good, his wild years behind him. He explains that he was initially prompted to make Alpha Papa, the Alan Partridge movie, after reading a blog that said he shouldn't. At night, alone, he sometimes dips below the line on Guardian articles, just to check what people are saying about him. "I hear that Steve Coogan reads the Guardian," said one post that he read. "Hi Steve!"

He is suspicious of arcs and angles and a newspaper script he can't write for himself. The more he thinks about this, the more his exasperation grows. Journalists, he claims, are always trawling through old cuttings as though these are somehow defining. "The back catalogue of my past misdemeanours." He sips his tea and pulls a face. "And all of that stuff was a long time ago. It's ancient history for me. But what I refuse to do is engage in some sort of justification and say, 'Oh, you know what? I also like going for country walks and reading books.' Fuck you. I'm not going to jump through hoops to redress your perception. It's none of your business. If you think my work is shit, that will upset me, but at least it's legit. My life now is probably much more PR-friendly than it was in the past. But even the good stuff that makes me look good? It's still none of your fucking business."

His blood is up, his colour rising. He takes his cap from the floor and screws it back on his head, all but daring the staff to throw him out on his ear. These days, he says, he's not afraid of a fight. He can say what he likes without fear of the consequences.

Wasn't he always that way? No, he says. "There was a time, 15 years ago, when I wouldn't say boo to a goose. I didn't want to express any political views, I didn't want to alienate anyone. But as you get older you get more comfortable in your skin. I don't need everyone to like me all of the time. I'm comfortable with the fact that 30% of people might think I'm a cunt. That's probably all right. I can still get elected." I'm not sure that he is comfortable: I can't think when he is. But he's keeping the tensions in check, and that's what works for him.

Coogan shakes my hand briskly and then gestures at his cap. Before he leaves, he wants to take hold of the narrative and script his own exit. "There you go," he says cheerfully. "Me wearing the hat. That shows that I'm still hanging on to my punk-rock credentials. Put that in the piece."

• Philomena is out on 1 November

• More on Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa

• More on The Look of Love

• More on Philomena