A spiny pencil urchin hangs in a perspex case next to the lacy sheath of a glass sponge. Nearby lie the cracked-open skulls of crows and robins, a collection of knobbly seed pods and a globular lump of brain coral. Eerily lit from below by glowing tables, which themselves seem to grow from the floor like mutant water lilies, it looks like the set of a space-age Natural History Museum. In fact, this curious collection of bones and barnacles is the future of architecture – according to Michael Pawlyn.

“Nature is a largely untapped sourcebook for architects,” he says, standing in the Architecture Foundation’s south London gallery, surrounded by a wunderkammer of odds and ends from the natural world that he has assembled for his first solo exhibition, Designing with Nature. “In the past, designers have tended to focus on just a few examples, like termite mounds or shell structures, but I really think nature holds the answers to making buildings that are fit for the next billion years.”

Through his practice, Exploration Architecture, Pawlyn has been investigating the biomimicry’s design potential for the past seven years, exploring what everything from lichen to lizards have to offer the design of our built environment. Trained as an architect, he worked for Nicholas Grimshaw for 10 years and was central to the team that conceived the Eden Project, leading the design of the temperate and humid biomes, which erupt from the former clay pit in Cornwall like a sci-fi fungus.

“All my work is driven by a frustration with the word ‘sustainable’,” he says. “It suggests something that is just about good enough, but we need to be looking at truly restorative solutions. We’ve gone from dominating nature to learning from bits of it, but now we should be looking at total reconciliation with the natural world.”

And Pawlyn thinks the best solutions are already out there, lurking in a rich seam of natural evolution waiting to be mined.

“Take the spookfish,” he says. “It lives 1,000m below the surface of the sea, so it has developed two sets of eyes that use mirrors to focus the faintest glimmers of light on to its retina.” These “diverticular” eyes can detect bioluminescent light from other creatures many metres away – both above and below – allowing the fish to keep track of predators and prey in the murky gloom.

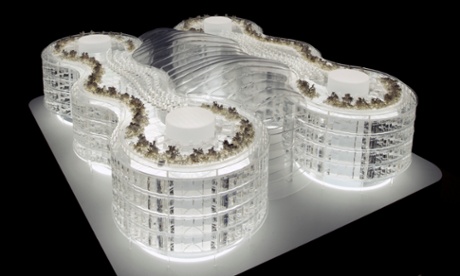

Buildings might not need to keep a lookout for predators by night, but they do need to maximise the amount of natural light they receive, particularly in deep-plan office blocks that all too often have artificial lights on throughout the day. So, learning from the spookfish, Pawlyn and his team have developed an office building with a kind of fish-eye mirror lens in its atrium, designed to reflect light deep into the office floors.

The building also steals tips from some other friends from the deep, namely the brittle sea star and the living stone plant. Scientists recently discovered that the sea star, which is otherwise blind, has a unique exoskeleton covered with crystalline lenses, forming an all-seeing eye across its skin. Stone plants, meanwhile, grow underground and have developed translucent pockets in their leaves to allow light to reach photosynthetic tissues deep within the subterranean foliage. Both of these natural structures have informed the design of the office block’s facade and roof, which incorporate daylight tubes and fibre optics to channel light down to the floors below. Pawlyn says the resulting building would use 50% less glass than an equivalent office block of the same floor area, while the abundance of natural light would result in a 10% increase in employee productivity. There is sadly no way of testing these bold claims, as the project – like most of the designs in the exhibition – is a self-initiated speculation and remains unbuilt.

But one experiment that has already yielded impressive real-world results can be found on what was formerly a hectare of dusty sand in Qatar, where a pilot project aimed at “greening the desert” is underway. Taking inspiration, as ever, from a curiously named creature, the Sahara Forest Project draws key lessons from the Namibian fog-basking beetle, which has evolved a cunning way of harvesting its own fresh water in the desert – collecting condensation on its bumpy shell, which runs down into its mouth.

The beetle’s principles have been used to develop a complex of seawater-cooled greenhouses, in which the evaporation of seawater is increased to create higher humidity, while a large surface area is created for condensation. In this way, saline water can be turned into fresh water just using the sun, the wind and a small amount of pumping energy.

“I was astonished that they managed to grow cucumbers and tomatoes throughout the Qatari summer,” says Pawlyn. “And there is also a useful byproduct that could have implications for construction.” He shows me a gnarled block the size of a shoebox, which looks like a sponge dipped in plaster. It turns out this is an evaporator pad from one of the seawater tanks, which has become encrusted with calcium carbonate as the water has evaporated – forming a handy lightweight building block.

Nearby lies another encrusted object that looks like a bundle of pipes dredged from the Titanic, or a giant kettle filament suffering from a serious case of limescale. This, says Pawlyn, is the future of “biorock”, the result of passing a low electric current through a metal armature immersed in the sea, attracting mineral deposition over time.

“It’s a lesson taken from the coccolithophore,” he says, pointing to an electron micrograph image of what looks like an elaborate ball of crochet, all interlocking woven circles. “It’s a single-cell marine organism, enclosed in a kind of cage made from calcium carbonate, which it pulls from the surrounding seawater. Over the years, these organisms capture carbon and fall to the sea floor, building up layers of limestone.”

Using the coccolithophore’s principles, he says, we can potentially “grow” buildings from atmospheric carbon, employing a technique that was originally developed by marine biologist Thomas Goreau for rebuilding coral reefs. A project currently being designed in collaboration with Queens University, Belfast, could see the first biorock pavilion grown underwater, using a wire mesh structure in the form of a ribbed seashell. At a deposition rate of 50mm a year, it’s not exactly rapid-response construction, although Pawlyn estimates the lightweight shell structure they have designed could be fully grown in only 18 months.

Beyond the projects on show, the walls of the exhibition are lined with 20 more creatures and their as-yet untapped potential, from the orbweaver spider to the mud-dauber wasp, which could inform our built environment over the coming millennia if Pawlyn has his way. “We just have to look a bit harder,” he says. “The answers are already out there – perfected by 3.6bn years of research and development.”

• Michael Pawlyn will deliver a lecture at the Architecture Foundation tonight, Monday 17 February at 7pm. A further panel discussion, Designing with Parameters, chaired by Marcos Cruz and featuring Michael Pawlyn, Rupert Soar, Nerea Calvillo and Patrik Schumacher, will take place on 27 February at 7pm.