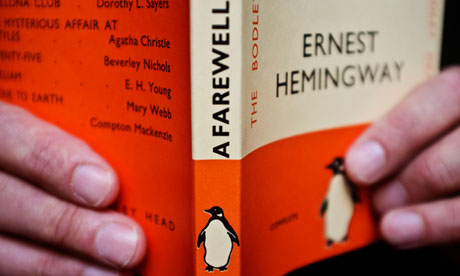

The reactions to news that the publishing arms of Bertelsmann and Pearson are merging, creating the biggest publisher in the world in Penguin Random House, can be summed up in one word: negative. There are, however, three strands to this glass-half-emptiness – and all of them, when you scratch beneath the surface, spectacularly miss the point.

First, there's pessimism – evident in bleak industry forecasts right, left and centre based on the current state of the trade, in its worst shape in living memory. Print sales are falling – down 11% in 2011, the trend continuing in 2012 – while bookshops, both specialist and chain, are closing. Borders has gone, Waterstones is in turmoil, and independent booksellers the length and breadth of the country are vanishing. Publishers, meanwhile, are being squeezed by the last remnants of the High Street, struggling to make established margins pay. Last but not least, advances are falling, the midlist novelist looking like an endangered species and writing for a living no longer an option for the vast majority of published let alone aspiring authors.

Second, there's the feeling of being under threat. Self-published authors, the renegades of the industry, are seemingly side-stepping legacy publishing to build direct relationships with what Marjorie Scardino, chief executive of Pearson, calls "reader constituencies" – cutting out the middle man. Digital books, though still only representing a tiny share of the market – 6% at the last count – are becoming more popular. Growth would be met with optimism in any other industry, but not publishing; not when no one knows how the trend will pan out – hence, the digital threat. Amazon is a behemoth hitherto unknown, Jeff Bezos making inroads not only in areas formerly reserved for bricks and mortar, but also publishers, the retailer touting its KDP Select as well as acquiring houses and churning out product of its own.

Third, as with all things negative, there's fear. Jumpy publishers worry that people will stop reading altogether, not least because they've lost touch and Amazon's stolen a march; after all, Bezos knows exactly who his customers are and what they're buying, and how many publishers can say that? Authors, in turn, are wary of their slightly more vainglorious cousins, the self-published, and writing ending up nothing more than what agent Jonny Geller calls a "passionate indulgence", the refrain of "pay the writer" sounding more and more like an ode to time long past.

But we all know that two minuses make a plus, so could all this death-of-the-book negativity actually represent a positive? Rupert Murdoch, not so much through gritted teeth as sour grapes, called the Penguin Random House deal a "faux merger" – suggesting that it won't mean a thing in the long run. No one really believes that, probably least of all Murdoch. But the fact is that, viewed from the bottom up, this could well be an opportunity for independent publishing to prove its vitality.

The merger is an example of the big boys battening down the hatches; no matter what they say, this isn't about exploiting "high-growth emerging markets". Profile founder Andrew Franklin is bang on when he argues that the profit-and-loss concerns of any merger always trump the ideology. He fails to flag up the downsides of his own acquisition of tiny Birmingham press Tindal Street, although few, admittedly, have voiced comparable concerns – maybe because any effect on quality is likely in the case of Profile Tindal (or whatever it'll be called) to be balanced by a strengthening of the "indie constituency".

In any recession, the vanguard is to be found beyond the mainstream – and risks taken by those typically seen as outsiders. Indies, as they always do, will be seen as the risk-takers in a climate of doom and gloom, nurturing talent and publishing books not deemed safe enough for the panicky, profit-driven corporations.

Only a few months ago, on announcement of the Booker longlist, the trade witnessed proof – and maybe, just maybe, a preview of things to come. In a radically different kind of collaboration between publishers, independent Faber helped much smaller independent And Other Stories put out a mass market edition of Swimming Home. Deborah Levy's book, the second indie novel on the eventual shortlist, subsequently enjoyed what website à la data called a "bombastic" increase in sales.

If that's not an example of indies punching above their weight, partnering to produce an even better product without compromise or laying off staff – and managing to make a buck in the process – then I don't know what is.

Gavin James Bower is editorial director at independent publisher Quartet Books.