The boy – wearing a tatty frock coat and waistcoat – runs across a station forecourt, through iron columns, steam and glass. Turn the page, and he enters the mouth of a square tunnel, into the shadows; he pauses, against the tunnel wall, to ensure he is unobserved. Turn again, and we see, close-up, his arm reach towards an ornate iron grate in the wall; and then – in the graphic equivalent of a cinema zoom-shot – we see his boot, with holes in the sole, disappearing into a duct, and the station's concealed innards and passages.

This opening sequence from the best-selling book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by the American children's illustrator and author Brian Selznick, runs like a movie reel as you turn those pages – which is fitting for a number of reasons. Firstly, because the book is the inspiration for Martin Scorsese's magnificent film Hugo, which is up for 11 Academy Awards in a fortnight's time. And secondly because the book is in part about film: the wonder and magic of silent movies in general, and the work of that genius of early French cinema Georges Méliès in particular. (Which is all the more extraordinary for the fact that the book was published in 2007, long before the film The Artist was made – also a tribute to silent film – against which Hugo is pitched almost head-to-head at the Oscars.)

The story is that of an orphaned boy who lives in the hidden chambers of Montparnasse station in the early 1930s, where he keeps the clocks working. The boy's great love and purpose is a mysterious automaton, the only legacy of his father, who was killed in a museum fire. Hugo's attempts to repair the machine bring him to another orphan, Isabelle, who lives in the care of an old man who keeps the station's toyshop, from whom Hugo steals mechanical parts for his enterprise. The automaton circuitously reveals the old man as the great film director Georges Méliès, who has, in despair, destroyed almost all trace of his work after the ravages of the first world war. In reality, Méliès, a former conjurer and magician, did the same: he was rediscovered working in a Montparnasse toyshop, and his films were restored as iconic treasures of silent cinema.

The result is a doorstopper book that has sold more than a million copies, and a piece of alchemic magic on screen. Scorsese's first excursion into what the Americans call "family cinema" is the adventure of a lone child in a tradition as established as Oliver Twist. It is a homage not only to silent cinema and Méliès but to Selznick's book. Most strikingly, Scorsese's film is – for all its state-of-the-art 3D and its director's masterful eye – closer to, and more respectful of, the work on paper than any adaptation that comes to mind.

"Yet everything is enhanced," says Selznick, in his only interview with a British newspaper ahead of the Oscars. "The camera movements are based on my drawings, but bigger, grander and more operatic than anything I could have imagined." The sequences are an exact recreation of what Selznick has drawn; in no way have the images described or portrayed on the page been imposed upon, unlike most film adaptations of children's books. The drawings are, rather, brought into motion "and deepened in space, made sculptural and given meaning by the 3D," says Selznick, so that book and film become inseparable, mutually regenerative, and the combination something greater than the sum of its parts to a degree that has no equivalent in modern children's literature or cinema.

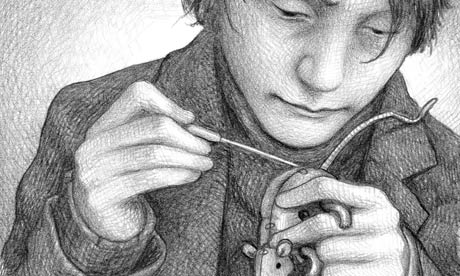

And appropriately so, for just as Scorsese is a colossus of the screen, so Selznick is emerging as a leading visionary illustrator set to impact the American – and, next, British – mainstream. Indeed it is to the master Maurice Sendak that he fittingly dedicates a new book, Wonderstruck, an even stranger, and more searing adventure. The fact that Selznick has achieved his success as a monochrome line illustrator working painstakingly in pencil on a tiny scale – "my drawings are 3in x 5in, and magnified" – makes it all the more extraordinary in an age swamped by computerised phantasmagoria and gimmickry.

Brian Selznick, now 45, was born in East Brunswick, New Jersey; his grandfather was a cousin to David O Selznick, producer of the original King Kong and Gone with the Wind. "I come," he once joked, "from the dry-cleaning side of the family." But young Brian Selznick soon displayed his family's gift for the visual: while studying at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, he also studied set design at nearby Brown University. But it was only while working at the famous children's bookshop Eeyore's Books in Manhattan that he decided to become an illustrator. Much of his early work went out of print, but as happened to Philip Pullman's early novels when he became famous, the work has been catapulted back into view since the success of Hugo. Selznick won the prestigious Caldecott award (equivalent to our Kate Greenaway medal for illustration) for Hugo Cabret in 2008. After the Oscars, and whatever happens to Wonderstruck in the bookshops and cinema, many more seem set to follow.

As the son of a children's author -illustrator [Shirley Hughes] myself, I have to ask Selznick about technique.These are remarkable drawings of vivid characters and raw, intimate emotion which develop slowly over hundreds of pages against backdrops of urban landscapes or vast spaces of sky, storms and emptiness; they are achieved by painstaking cross-hatching, which, in Hugo Cabret, recall fin-de-siècle etching and, in Wonderstruck, are evocative of American precisionist artists enthralled by industrialisation. And, of course, they echo the early movies.

"I work on this very small scale with an HB pencil," he explains, "often with a magnifying glass. Part of what I was doing was to get the tone of black and white early French film. There was this richness in the textures of early cinema" – conveyed on paper by the magnification and cross-hatching. "It's a way to achieve a certain kind of shading I want. I like drawing light, but of course to do that, you are drawing darkness. I've always cross-hatched: I have a copy I did of a Leonardo angel when I was 10, and it's all proto-cross-hatching," he laughs.

"But I'm a fairly mechanical worker – I tend not to think about themes so much as plot. I want to get the feeling right. If it's moving through tunnels, I ask myself, what is it like to move through tunnels?" And what about the close-up faces, and above all eyes, that move through these pages? "I read that Dickens used to have a mirror on his desk and made facial expressions into it to help him describe what he saw. I keep a mirror to help me – I furrow my brow, I raise my eyebrows…" The result is a world more realist – or at least markedly less surrealist – than that of, say, the Australian, Shaun Tan, whose book The Arrival deals with migration in a similar tonality but different atmosphere, and whose film animation The Lost Thing won an Oscar last year.

And being also the descendant of generations of French clockmakers, I have to ask Selznick about this adoration of the mysteries of clocks and mechanics that is the bedrock of Hugo Cabret. "It comes from my interest in magic," replies the artist – one of his early books is about Houdini – "from witnessing something you cannot explain unless you are the person doing it or designing it. What interests me about clocks is that everything is hand-made, and yet to the person looking at the clock, something magical is happening that cannot be explained unless you are the clockmaker. Just as a magician does something, a trick, that only he knows the secret of. It goes back to Ancient Greece and to the Golem: if machines can imitate life, then what is life? Then I read a book by Gaby Wood, Edison's Eve, about automata, and there's a chapter on Méliès's collection, and I began to think about the connections between clock-making, automata and magic – and the magic of film that was also hand-made, the costumes, the sets, the colouring. There is a sense in all these things that they are done by hand, and there's a sense of purpose. Hugo talks about the sadness of broken machines, and how fixing them gives a sense of purpose."

Selznick uses the term "making Hugo", rather than "writing" or "drawing" the book. This is essential to the enterprise. There is something germinally pre-digital about the book itself, beyond the narrative and setting. The book is a thing of beauty and material mass; Selznick's technique of magnifying tiny pencil drawings creates an impression of texture whereby the lead will come off on your fingers. Neither The Invention of Hugo Cabret nor Wonderstruck will become ebooks, he insists, nor can one imagine how they would work as such. Books are themselves essential to the narrative in both stories. This is about the life of the book – and the future of the defiant craft of the illustrator and his pencil, "the hand of the artist", as Selznick puts it, in a computer age, and of materiality in a time of virtuality.

My mother, Shirley Hughes, talks often about the book as a remarkable piece of technology, and Selznick says this: "People use computers more and more, which erase the hand of the artist – and I wanted to do something in which you see the hand of the artist… I wanted to stretch as far as possible after what I could do with the technology of bookmaking – the book is authentic and I wanted to use the technology of the book to achieve authenticity. I'm interested in the act of turning a page, to tell a story by moving forward physically. In picture books, you turn a page at the pace you want, you become the driving force behind the narrative."

And, Selznick adds: "I wanted also to recreate the experience of a movie in the turning of pages, to reflect in the page-turning what Hitchcock and Truffaut were doing with their cameras." After all, "some of the best books are about books, and some of the best films are about film" – and with Hugo, we have a perpetual motion of correspondence between both: "We have a book that celebrates movies, and now a movie that celebrates books."

The choice of period is also didactic: "In terms of popular culture, I wanted to set my stories in a world where there were no cellphones, while hoping to relate some basic themes, some fundamentals, to kids today." Of those basic things, none is more seminal to great children's literature than orphan-hood. Hugo and Isabelle in Hugo Cabret and Ben in Wonderstruck are all orphans, while Rose in Wonderstruck, is rejected by both parents.

"It's funny," says Selznick. "I grew up in a happy family with loving parents, but I've killed off a lot of parents in these books. The orphan in children's literature," he argues, "allows the child protagonist to move the story forward themselves. I think that, however happy a family, every intelligent child thinks: 'How did I come to be born to these parents?' – it is about finding your place in the world. It's about purpose and the broken machine: I had to work from the question: why is a 12-year-old going through the trash after a fire at a museum looking for a broken machine?' It's about the importance of making your own family. Which Hugo does, to achieve the perfect happy ending. In Wonderstruck, however, the ending is more oblique."

This brings us to the heart of Selznick's work: Wonderstruck is a darker, more adventurous book than Hugo Cabret. It operates on two levels: two stories, one told in drawings and set in the 1920s, another in text, set in the 1970s – which dramatically entwine. In the drawn 1920s, Rose is deaf, rejected by her mother whom she adores, and persecuted by her father. She runs away from home, across the Harlem river from New Jersey to New York, where her older brother, takes her in. In the written 1970s, Ben is an orphan in Minnesota, who also escapes to New York in pursuit of the father he never knew, after losing the hearing in his one "good" ear. Stripped of all he has but his determination and a few clues, he sets out to find his father and … well, I mustn't spoil the ending and meeting of the two narratives – only to say, the knee-weakening denouement is driven by the Natural History Museum, a book and a diorama of wolves patrolling the snows of Minnesota.

"I wanted to write a love letter to New York City," laughs Selznick, "but my ending, Ben's eventual happiness, is when he is looking at the stars during New York's worst moment, the blackout of 1977, which most people remember as a very scary experience."

The cogency of and rip-tide beneath both books lies in the notion of the other, the lost, in a cruel world, finding their own – and their place in something bigger than harsh society. But one thing is strange: in the many, many American articles about Selznick, his deep interest in deafness and what he calls "deaf culture" is of course discussed. Wonderstruck is nothing if not a charter for anyone deaf, and renitent celebration of their condition (not least with regard to silent movies!). But no article I can find relates these sympathetic and defiant portrayals of the deaf "other" to the fact that Selznick is gay – whether out of polite uneasiness, political correctness or wariness of prejudice in the American outback.

The taboo is certainly not Selznick's, for he is most eloquent about the link: "Of course there's a connection, there are many strong parallels", not least that "my boyfriend happens to teach with two of the leading deaf scholars in the country". Just as the adult Rose, in her account at the end, describes the liberation of finding peers and love when she finally goes to deaf school, so, says Selznick, "when I was growing up there was just this part of me that was who I was, and I thought I was alone in that. I didn't know there were other gay people out there – until I got out there! I think every child will feel like that at some point, for whatever reason, and I think it can give your life context in a rich way.

"These things are just part of who you are," he continues, and whatever the tribulations and persecutions, "you must fit in somewhere", even if it is in the wider universe and its vast indifference. Or, more tangibly, "in a museum, where there is a place for everything. I think everything belongs in a certain place, for kids who feel they don't belong anywhere. A museum is an institution like a library where everything has a place, everything belongs."

Dividing his life between Brooklyn on America's eastern shore and San Diego on its Pacific edge, Selznick waits, if there's any justice in the world, for the film of his book to become the toast of Hollywood. Asked by an American magazine about the experience of having his book adapted by Scorsese and becoming a huge hit, Selznick answered "It's such a thrill. I mean, Scorsese is the best, and when I went on set, everybody had a copy of the book. Scorsese always kept a few on hand, so he could give them to people so they'd understand what he wanted in the shot." Selznick was told by Dante Ferretti, the production designer: "I just did everything you drew."