Nick Frost is late. He hates being late. As he walks through the door of the railway café where we were meant to meet 20 minutes ago, he is flustered and jittery. He sits, trailing a cloud of apologies about delayed cab drivers and bad traffic, and orders a coffee.

Still apologising, he puts his mobile and noise-reducing headphones on the table, and then, without drawing breath, minutely rearranges everything he's just placed in front of him, pushing his mobile a millimetre this way, sliding the headphones a quarter of an inch in the other direction until he's satisfied with the placement. Then he starts saying sorry again.

It's fine, I tell him. After all, I once had to wait three hours for Mariah Carey. In the pantheon of celebrity lateness, this barely merits a mention. But he is noticeably stressed by his own lack of punctuality, which is surprising given that Frost has built a successful career on laid-back blokeishness and laconic wit. His onscreen persona, minted by memorable turns in cult sitcoms (Spaced), buddy movies (Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz and The World's End) and mildly humorous Brit flicks (The Boat That Rocked, Cuban Fury), is defined by an approachable, laddish and somewhat chaotic charm.

But in real life is he someone who needs to be in control? "Yeah, I guess," he says. "I share an office – I've been writing with a couple of mates of mine and it's a lot of fun, but I realised I didn't like their stuff coming on to my half of the desk… I have a thing with pillows. I have to make sure I fluff them and then they can't be touched until I put my head on them."

And yet for all his organisational compulsiveness, Frost readily admits he never planned the way his life turned out. He became an actor because in his late 20s he simply happened to be a waiter in the same north London Mexican restaurant as the girlfriend of a rising stand-up comedian called Simon Pegg. The two of them met, bonded over a love of Star Wars, lived together and famously ended up sharing a bed. "It never felt weird. It felt like when you were a kid and a mate stayed over."

Pegg wrote Spaced, basing it loosely on the pair's aimless, sloth-like lifestyle of computer games and drinking beer on the sofa in their underpants. When it aired on Channel 4 in 1999, it was nominated for a clutch of awards including a Bafta and an International Emmy, and Pegg and Frost were on their way to becoming Britain's most famous comedy double-act since… well, if not Morecambe and Wise, then at least the Two Ronnies. Or maybe Ant and Dec.

Pegg and Frost went on to star in the so-called Three Flavours Cornetto trilogy – a trio of films written by Pegg and directed by their friend Edgar Wright, kicking off with the box-office hit Shaun of the Dead in 2004. Soon Frost was being recognised on the street. "I've been in the bathroom and kids come in and say: 'You're that bloke off the telly. Yeah. Your films are shit, mate.'" He grimaces. "It's very emasculating. My sense is to fight them, but as I'm a 42-year-old dad, they'd do me."

Still, it hasn't all been embarrassing urinal-based confrontations: by 2011, Steven Spielberg was casting Pegg and Frost as the Thompson twins in The Adventures of Tintin. That same year, the duo wrote and starred in Paul, a sci-fi road-trip movie that grossed almost $100m.

"I've never had a plan," Frost insists. "I've always just followed my heart and it's turned out all right."

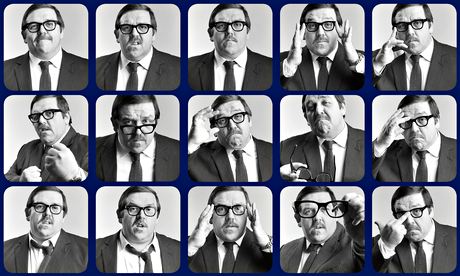

Recently, he has been striking out on his own. Earlier this year, Frost starred in Cuban Fury as an overweight office worker who takes up salsa in a bid to impress a girl. He will shortly be appearing on our screens in the title role of Mr Sloane, a Sky Atlantic comedy series written by Curb Your Enthusiasm producer and director Robert B Weide. Mr Sloane is a middle-aged former accountant living in Watford in the 1960s – a decade in which Frost looks effortlessly at home. "I think it's because I'm quite plain aesthetically," he says. "It enables you to inhabit anyone and it doesn't seem odd."

Mr Sloane is undergoing a personal crisis after losing both his job and his wife (played by Olivia Colman). In fact, the first episode opens with Mr Sloane trying to hang himself.

That's quite dark for a primetime comedy caper, isn't it?

"I loved the fact that a sitcom starts with a failed suicide attempt," says Frost, lifting his coffee mug with ursine hands that make the china look like doll's-house crockery. "For me and my comic sensibilities, that's perfect. That's where I want to be – it's funny, but it's tragic and violent and explosive. I can relate to that."

And then, almost as an afterthought, he adds: "It happened to my uncle, but he was so fat the rope broke."

You mean your uncle tried to commit suicide? Frost nods. Why? He brushes the question away, suddenly uncomfortable. "It was just as an aside," he says.

Later he tells me that when he was 10 his older sister died of an asthma attack. She was 18 and an up-and-coming singer-songwriter.

"Yeah, that was very odd… I came downstairs and I saw the television was off and I knew that something had happened because you'd only have the telly off if someone had died." He smiles grimly. To this day he can't stand "the crushing silence of having nothing electronic on". He'll leave the TV on even if he's not watching it, just for the reassurance of the background noise. "My wife hates it."

Frost's conversation is full of revelations like this. His life has been punctuated by a shocking level of tragedy, and throughout the interview he offers up nuggets of traumatic personal experience so casually that on several occasions I have to check I've heard him correctly. He asks me not to include some of the detail of what he's been through for family reasons and also because he has a horror of exploiting personal grief for the purpose of promoting a TV show. But at the same time he wants to be honest, to give me a context for his decisions, and I can see him struggling with the tension between these two contrasting desires with every answer he gives.

Unlike most of his onscreen characters, Frost is a deep thinker. Although he went to Catholic school in Ilford, Essex, he no longer believes in God, but instead places his faith "in people and science" rather than "a big man with a beard who punishes us for being bad".

He finds it "frustrating" to be seen purely as a comic actor and cites Robin Williams as someone he admires for having made the transition from comedy to more serious film roles. One of his favourite authors is Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. For a while he wanted to be a novelist and had romantic visions of writing "in a draughty garret with a blanket around myself". He catches himself: "I'm coming across as a horrible, bleak man, aren't I?"

There are reasons for his bleakness. When Frost was 15, just three years after his sister died, the family business selling office furniture went bust. Until then his childhood had been financially secure: they lived in a double-fronted house in Redbridge and his father drove a Jaguar. Overnight everything changed. They lost their home. Neighbours took them in.

"We were put on the street," Frost recalls. "We had to go and live next door in one room – the three of us and our massive Alsatian, Sheba, and it was while we were in that room that I caught…" He stops, searching for the right word. "I witnessed…" He tries again: "I was the first on the scene of my mum having a stroke, through the stress." There is a brief pause. "And then I left school to support them financially."

Frost got a job in a shipping company. They were moved to a "horrible block of flats" by the council. "So the fall from grace was complete and my parents were just never the same again. I wasn't a kid any more at that point."

The estate was tough – "It was fucking so lucky that I had a big dog. No one fucks with you if you have a big dog" – but he stuck it out for two years before a friend intervened and told him to get out. "He could see I was derailling slightly as a person," says Frost. The friend suggested Frost joined him on a kibbutz in Israel. He'd intended to go for three months, but liked the camaraderie so much he ended up staying for two years. At that stage, he says, "friendship was all I had".

His childhood has left him with an innate dislike for waste or unnecessary extravagance, and I wonder what he makes of the current government's policies on austerity.

"There's a loss of community, and the majority of people don't want to get involved [in other people's problems]," Frost says, neatly sidestepping the question. "People are afraid of it. I don't think you can criticise that."

Does he vote? "Yeah – I vote because it's important to vote, but in terms of change I still have a working-class sensibility, and my bullshit meter is so finely tuned that as soon as I hear bullshit I know it as that and I can't unhear it. Politics is not about politics any more. It's about big business. It's not about helping the right people." He sips his coffee. "It's such a big issue that it feels flippant, me talking about it."

He has, unsurprisingly, a keen sense of his own mortality: "Yeah. I think about it a lot." His wife, Christina, is Swedish and he suspects at least part of the reason he gets on so well with his in-laws is that he shares that Scandinavian propensity for darkness and angst.

"They have good Christmases, too," he says. "They have a traditional Christmas – they sing songs on Christmas Eve, and it's the most pissed I get in a year. All we do in Britain is watch telly and a Bond film."

Frost and his wife live in Twickenham, southwest London, and have a son who is almost three. Frost doesn't want to put his child's name in the paper, but he shows me a photo on his phone of an extremely sweet toddler wearing a sombrero. "He likes to wear a sombrero when he's doing jigsaw puzzles," Frost says, grinning. "He's full of character."

Fatherhood has, he says, been a revelation. He took nine months off work when his son was born, which seemed like the most natural thing to do – "It's never been in my internal make-up to pull away from that or be afraid of it" – and there is a clear sense that Frost is relishing being a parent not just for the joy it brings, but also for the chance to give his son the secure childhood he was denied.

Towards the end of our time together, and after draining a second cup of coffee, Frost tells me a story about his teenage years, when he used to scour charity shops in the hope of coming across first editions of secondhand books. He had a dream of stumbling across something so valuable it would give his family financial certainty and be his own means of escape. Once, he found a first edition of Steven Spielberg's 1979 book adaptation of the earlier movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It would have made him a tidy sum. But for some reason, instead of selling it Frost kept hold of it.

Then three years ago he met Spielberg on the set of the Tintin movie and was able to ask the director to autograph it. Spielberg was astonished. "He said: 'Wow, how did you get this?'" recalls Frost. "That book's now in a safe in my house."

There is a quiet pride in his tone, a small sense of hard-won satisfaction in his smile. And even though I know Frost never plans anything, it is hard to think of a more perfect ending.

Mr Sloane premieres on Sky Atlantic HD in late May. The first scene is available now for all to view at youtube.com/skyfirstepisodes

More on Nick Frost

Losers in love: How Simon Pegg and Nick Frost found comedy chemistry