The Russian-speaking Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916) was, in his lifetime, a prolific popular writer and a failed playwright. In death, he defined a culture.

This role was confirmed only days after he died. About 1.5 million Jews were living in New York City; one out of seven lined the streets or watched from tenement fire escapes as the author's funeral procession wended its way from the Bronx through Manhattan to Brooklyn in what a local congressman called "the greatest spontaneous gathering of the people in the history of our city". Sholem Aleichem gave the Jews who emigrated from the Russian Pale a collective identity. Not a rabbi or teacher but a folks-mensh – a man of the people – he, or rather his characters, personified the pintele yid, a Yiddish idiom meaning the irreducible, indestructible essence of Jewishness.

Born in the Ukrainian town of Pereyaslav, Solomon Rabinowitz took his pen name from the Yiddish greeting "Peace be with you". His greatness as a writer was founded on an uncanny ventriloquism. Drawing on the richness of the Yiddish language, an Old German vernacular heavily infused with Hebrew and Slavic components, Sholem Aleichem conjured his best-known creations – the pious dairyman Tevye, the feckless speculator Menakhem Mendl and the irrepressible orphan Motl Peyse – through their distinctive voices. He treated these characters as if they were real, and many of his early readers believed that they were.

As Sholem Aleichem invented the Jewish people, so they invented him. He was revered by Jewish communists as a homespun Gorky, the lone Yiddish author never banned in the Soviet Union; in newly established Israel, where Yiddish was a despised remnant of the diaspora, he was relegated to the children's shelf; Jewish American intellectuals read him as a sophisticated ironist and connoisseur of the absurd; while, beginning in the 1940s, assimilated American Jews prized the writer as the repository of shtetl tradition. Today, Sholem Aleichem is that tradition – best known for a work that involved many hands, had its premiere in 1964, nearly half a century after his death, and closed after 3,242 performances as the longest-running Broadway production of any sort. "There's no talking about Sholem Aleichem without talking about Fiddler on the Roof," Jeremy Dauber maintains on the first page of his new biography The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem.

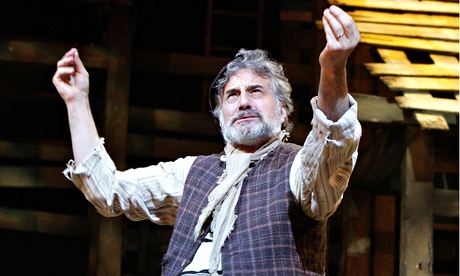

The last 50 pages of Dauber's book and the entirety of Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof by Alisa Solomon are devoted to this singular artefact, derived from the cycle of stories that Sholem Aleichem wrote about the humble dairyman and his five headstrong daughters – each of whom finds love with a different, problematic suitor. (These include a revolutionary, a poor man and, most grievously for Tevye and his wife, a Ukrainian Gentile.) Sholem Aleichem was unable to stage (or film) the Tevye stories during his lifetime but both happened soon after his death – most significantly when Maurice Schwartz, the epitome of America's Yiddish art theatre, took the role for himself. Schwartz's Tevye was less comic than Sholem Aleichem's, and his play, which involved Tevye's expulsion from his village, was understood, at least partially, as a response to the destruction visited on Jewish Galicia during the first world war.

Schwartz filmed Tevye during the summer of 1939, a version that, reflecting the terrifying rise in European antisemitism, was filled with foreboding. Four years later, when Maurice Samuel published his pioneering English-language anthology The World of Sholom Aleichem, the Yiddish writer was the signifier of an absence. Making discreet mention of the unfolding Holocaust, the New York Times reviewer called the book "a distinguished piece of writing [and] to all intents and purposes, a memorial to that world, for generations injured and humiliated and now in the process of extinction". The World of Sholom Aleichem went into 10 printings, inspiring two bestselling anthologies of the author's stories. One was optioned by the Broadway titans Rodgers and Hammerstein, but the first English language staging of Sholem Aleichem came from elsewhere beyond the Pale.

Arnold Perl's The World of Sholom Aleichem – a dramatisation of two Sholem Aleichem stories and another by Polish Yiddish writer IL Peretz – premiered in 1953 in the basement ballroom of a mid-town Manhattan hotel. The no-frills production gave the Yiddish writer additional symbolic baggage as it was steeped in social consciousness and cast almost entirely with actors who had been blacklisted for their communist affiliations. Praised by the New York Times as well as the Daily Worker, it was one of the founding works of what came to be known as off‑Broadway. The play reached an even wider audience when it was televised in 1959. The show's producers again made a political point by featuring a number of blacklisted actors including Zero Mostel.

Reading this on mobile? Click here to view video

The critics praised The World of Sholom Aleichem but they adored Mostel, whose performance as a befuddled teacher is characterised by magnificent humour and an exquisite grace. The televised film not only made Broadway safe for the musical version of Tevye that the young team of Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick were planning, it made it essential that Mostel should star. Still, during the years it took to raise the money for Fiddler on the Roof, other potential Tevyes were bruited, including Howard Da Silva, star of the off-Broadway The World of Sholom Aleichem, Danny Kaye, Rod Steiger, and Eli Wallach. The degree to which the producers wanted him may be gauged by his deal – a cool $4,000 a week against 10% of the gross box office.

Solomon tells the Fiddler backstory with wit and verve, although her protagonist is less Mostel than another sacred monster, the show's director-choreographer Jerome Robbins (born Rabinowitz), who had made his acting debut 25 years before under the auspices of Schwartz and, revisiting his roots with a vengeance, stormed into the project "like a gale force, bringing fresh perspective and exhilaration". Robbins recruited Schwartz's one-time designer (and Marc Chagall's associate) Boris Aronson, showered the cast with copies of Roman Vishniac's photographs of prewar Polish Jews, made ethnographic expeditions to Hassidic weddings, and held multiple screenings of the 1928 Soviet Sholem Aleichem adaptation known in the US as Laughter Through Tears.

Robbins effected the master synthesis, fusing the Broadway musical theatre (which had largely been the province of assimilated American Jews) and the new artefacts of old world Jewish authenticity, as well as an underlying seriousness. Dauber sees Fiddler as "the Judaising of American culture" – but it was equally the ultimate Americanisation of Jewish culture. The show depicted generational conflict, a staple of American Yiddish theatre and the "melting pot" movies of the 1920s, even as it revolted against what Solomon calls "the conventions of a mid-century book musical – no overture, no flirty chorus girls, no reprises, no simple plot line, no happy denouement". Indeed, there was even a pogrom.

From the making of Fiddler, Solomon proceeds to discuss the ways in which the play, at once emblematic of tribal solidarity and suggestive of social upheaval, constructed and consecrated a new Jewish identity. She details the circumstances of the 1972 film and devotes separate chapters to key productions – in Israel, in Poland and a staging by a cast of black and Puerto Rican children in a Brooklyn public school amid the bitter racial polarisation of the late 60s.

Fiddler, Solomon notes, gave "Gentile post-McCarthy America – and the world – the Jews it could, and wanted to, love". Evidently so, although I should admit that I don't much care for Fiddler on the Roof and never have. The show opened when I was a teenager who, having grown up in a New York City neighbourhood so Jewish I had little sense of belonging to a minority, was working through his own identity as a Jew. Fiddler, which I knew only from the album, seemed smug, middle class and weirdly triumphalist. (My Jews were Kafka and Lenny Bruce.) The degree to which the show was, as Solomon puts it, "deeply saturated with the memory of the Holocaust" was lost on me. I got Porgy and Bess and even West Side Story, but I could never have imagined Fiddler's enduring universality.

A half-century after its premiere, the musical's manufactured celebration of tradition has, Solomon notes, itself become tradition. For Dauber, "there's no talking about Yiddish … without talking about Fiddler". It is a work that trumps taste; the total, inescapable package. (Just last month, sitting off the market square in Chefchaouen, Morocco, I heard the opening six notes of "If I Were a Rich Man" waft in from the night.) God might be denied, but not Fiddler on the Roof.

• Alisa Solomon's Wonder of Wonders is published by Metropolitan.