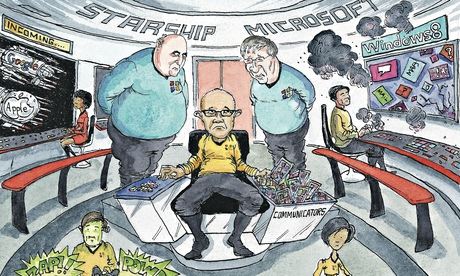

What would you most want as only the third-ever chief executive of a gigantic global company? Probably not to have your two predecessors on the board watching your every move, and the first boss giving up his role as chairman to take a more active day-to-day role.

But that is the prospect facing Satya Nadella, who is just finishing his first week as chief executive of Microsoft, where his predecessor for 14 years, Steve Ballmer, is still on the board (possibly until November) and co-founder Bill Gates (who preceded Ballmer) announcing plans to take a bigger role in the company.

Of course, if Nadella, who is 46 and a 22-year veteran of the company, is unhappy with this, he hasn't had time to say so. But for someone facing a sizeable challenge, it might be a couple of distractions too many. Publicity photos showed a relaxed-looking Nadella wearing a just-casual-enough hoodie and an energised expression. But below the calm surface, there's a lot of swimming going on.

Microsoft is hugely successful: it posted record revenue of $24.5bn (£15bn) for October-December 2013 and profit of $6.6bn (not a record: that came two years ago, with $7.8bn on revenue of $21.5bn). Google, however, is close behind: it has just recorded $16.9bn of revenue and $3.9bn in profit for the quarter. Its revenue has doubled in two years, its market capitalisation overtook Microsoft's at the end of 2012 – and Google gets far more attention.

Microsoft has to choose whether to play it safe – focusing on the large "enterprise" customers who generate so much of its profit by buying its Office software, Server suite and Windows licences – or to go after everything else too. Its Xbox games console business may start showing a profit (the new Xbox One is selling strongly), but its Windows Phone software has been a laggard while Google's Android and Apple's iOS have roared ahead. And consumers have been turning their noses up at PCs and Windows 8 in favour of tablet computers – another area where Microsoft lags badly.

In the huge consumer computing market, smartphones are the next wave. Adoption has been dramatically fast – there are about as many smartphones in use as there are PCs (1.5bn or so), with the mobile market growing much faster. How can Microsoft regain its resonance with consumer without a zippy consumer-facing brand? More important, how can it keep pace with Google, and catch up with Apple (whose iPhone generates more revenue than the whole of Microsoft)?

Nadella's expertise is with those business customers, and with "cloud" services such as Azure. Gates himself suggested years ago that Microsoft could transform the world through smart services connected to the devices on our desks, in our pockets and on our wrists. But it failed to do that, and left the door open to Google, which grabbed it through smartphone services such as Google Now.

Nadella needs to impress people once again with what Microsoft can do in software. It has built a search engine (Bing) from scratch; it's vying for first place in the games console market; it has large research departments with deep thinkers. Google's sugar-sensing contact lens for diabetics had been announced in 2012 by the same researcher in a project with Microsoft.

But while Gates will want Nadella to rouse the troops into writing world-beating software, will he be able to stop himself interfering? Nadella needs to shake up a very politicised culture, with much warring between divisions. Ballmer began knocking down the walls; Nadella has to finish it.

Gates is surely too wise to see himself as Microsoft's saviour; he's not Steve Jobs at Apple, returning to bail out the company he founded. But as long as he's bobbing along the corridors, who will truly be in charge? Nadella needs to have control. And that might mean asking Gates to take a long break while he does what he needs to for Microsoft to recapture its mojo.

A crackdown on bonuses … and City pay soars

Did the financial crisis ever happen? It's a question you may well ask yourself when you read Barclays' results on Tuesday and learn that the bank is paying out more in bonuses for 2013 than it did the year before. Despite promises of pay restraint, on Friday the bank handed out large bonuses to its 140,000 staff – for fear of them decamping to rivals – despite having tapped investors for £6bn of emergency cash last year.

If you are left shaking your head in confusion, think about the following. Barclays competes on the global stage – it really does take on Wall Street titans such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan – and it maintains that the US banks have not been feeling pressure to cut back on pay.

Also think about the EU bonus cap, which will restrict bonuses to 100% of salary, or 200% if shareholders give their approval at the annual meeting. This may well be scaring banks into handing out bigger pay deals than they might otherwise have wanted to for 2013, the last year before the limits come into force, and is also having the perverse effect of apparently pushing up the fixed part of remunerations (salary, benefits). Barclays has started to tell staff affected by the cap that they will get another payment in the form of monthly cheques this year, a kind of "allowance" to ensure they keep getting paid as much as they would have done without the bonus cap.

Barclays is not alone. All banks with European operations are exploring such additional payments. It is an extraordinary situation and one that the European Banking Authority, the pan-EU regulator, is watching. In any normal world the EBA would tell the banks to stop such wheezes (even if they are perfectly legal). But it won't get much support in the UK, where chancellor George Osborne is fighting the bonus rule and Bank of England governor Mark Carney has argued all along that it will lead to just such bigger payouts and make it harder to claw back pay when things go wrong. The EU has inadvertently opened the door to a pay bonanza in the City.

There's no money in first class – ask Ryanair

Michael O'Leary has taken a monastic vow of silence, but there are plenty of other airline bosses willing to be indiscreet in his absence. The boss of Air France-KLM broke an aviation taboo this week with the admission on every airline executive's lips: first-class cabins are a financial disaster. "No one makes money out of it. It's impossible," said Alexandre de Juniac, commenting as Norwegian Air pledged to make a profitable success of its new, low-cost operation between London and New York.

Perhaps it is time for low-cost, long-haul air travel to make its mark. Imagine: an entire A380 filled with 550 economy-class seats; a trolley run that would last the entire flight; and a Wi-Fi service to enable mass inflight FaceTiming, texting and phone calls.

Sounds like hell – but let it be a reminder to us all that, despite his recent disappearance from newsprint and the airwaves, O'Leary's legacy is still setting the agenda.