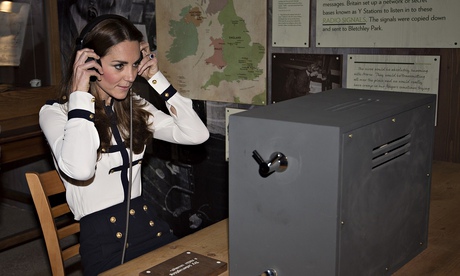

How intriguing to see the Duchess of Cambridge at Bletchley Park last week, apparently listening to recordings of radio intercepts. In a way, she was an appropriate royal to open the newly restored Bletchley Park, because her paternal grandmother worked there during the war, and one of the veterans present, Lady Marion Body, had known her. In one of those coincidences, Kate's visit to the epicentre of Britain's wartime code-breaking effort came on the same day that the Guardian published the Home Office's 48-page argument that GCHQ's wholesale, warrantless monitoring of British citizens' communications via Google, Facebook and Twitter is lawful because all these communications go to the US and back and are therefore "external" communications not covered by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (2000).

It's terrific that Bletchley Park has not only been rescued from the decay into which the site had fallen, but brilliantly restored, thanks to funding from the National Lottery (£5m), Google (which donated £500,000) and the internet security firm McAfee. I've been to the Park many times and for years going there was a melancholy experience, as one saw the depredations of time and weather inexorably outpacing the valiant efforts of the squads of volunteers who were trying to keep the place going.

Even at its lowest ebb, Bletchley had a magical aura. One felt something akin to what Abraham Lincoln tried to express when he visited Gettysburg: that something awe-inspiring had transpired here and that it should never be forgotten. The code-breaking that Bletchley Park achieved was an astonishing demonstration of the power of collective intelligence and determination in a quest to defeat the gravest threat that this country had ever faced.

When I was last there, the restoration was almost complete, and I was given a tour on non-disclosure terms, so I had seen what the duchess saw on Wednesday. The most striking bit is the restoration of Hut 6 exactly as it was, complete with all the accoutrements of the tweedy, pipe-smoking genuises who worked in it, right down to the ancient typewriters, bound notebooks and the Yard-O-Led mechanical pencil that one of them possessed.

Hut 6 is significant because that was where Gordon Welchman worked. He was a Cambridge mathematician who was one of the four earliest recruits to the Park. (The others were Alan Turing, Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry.) History has tended to overlook Welchman, who has always been overshadowed by Turing, so it's good to see that his importance has finally been acknowledged in a fine biography by Joel Greenberg. And yet he played as significant a role as Turing in Bletchley Park's success. When he arrived, he realised that the station was essentially a cottage industry in which a few mathematical genuises cracked codes. If it was to play a serious role in the allied war effort, he reasoned, it had to be turned into an organisation that took in intercepts at one end and outputted usable intelligence at the other, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The cottage industry had to be turned into a mass-production system.

And it was. One of Welchman's legacies was an organisation that, at its peak, employed 10,000 people working in shifts round the clock, all of whom had to be fed, watered, billeted, managed and transported – in conditions of the utmost secrecy. Even today, it looks like an astonishing managerial and administrative feat.

The most striking thing about Bletchley Park is the unanimity that it evokes. It is universally regarded as one of the glories of our age, evidence that sometimes human ingenuity and determination can produce truly wonderful results. And the reason for this unanimity is obvious when you think about it: Britain – and the world – faced an existential threat. The enemy that the country faced was unquestionably evil. If Hitler had triumphed, then the consequences would have been too terrible to contemplate. So there was, and is, no ambiguity about Bletchley Park.

And yet there's an ironic twist to the story. Two of the huts in the Park were where what is now GCHQ originated. The opinion polls suggest that most Britons think that the vast, sprawling organisation that is the modern GCHQ does a good or, at any rate, important job.

But there is a significant minority that is troubled about the "mission creep" that has been revealed by Edward Snowden and now confirmed by the Home Office document. The spooks are puzzled and offended by this. Do the critics not understand, they protest, that there's a war on? Ah, yes, but this "war on terror" is a rhetorical device, not the existential threat that Bletchley Park was created to combat. That's the difference and it matters.