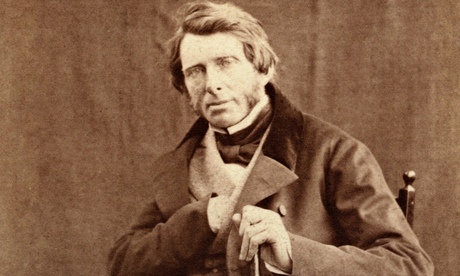

On behalf of John Ruskin, I would like to sue Mike Leigh for defamation of character. In Mr Turner, Leigh’s astonishing and sweepingly beautiful new film, the painter’s greatest champion has been traduced. Ruskin, played by Joshua McGuire, is a simpering Blackadderish caricature of an art intellectual: a lisping, red-headed, salon fop.

I almost felt physically sick when I saw him onscreen. Not just because of the extraordinary disconnect between Leigh and Timothy Spall’s brilliant realisation of Turner and the complete misrepresentation of Ruskin, but because this injustice is one that has been going on for more than a century. For Ruskin celebrated Turner above all other artists. While others decried his work, he wrote that his paintings “move and mingle among the pale stars, and rise up into the brightness of the illimitable heaven, whose soft, and blue eye gazes down into the deep waters of the sea for ever”. This posthumous portrait is unconscionable.

I’d barely recovered from the shock when along comes Emma Thompson’s equally wonderful but equally misleading Effie Gray. Two Ruskins in one season? Neither comes near to the truth. In Thompson’s film, the critic is centre-stage. His portrayal, by Greg Wise, is nearer the mark, at least visually. But Wise plays Ruskin as an austere ascetic, whose passions are reserved for the stones of Venice and the paint of the pre-Raphaelites. He cannot countenance the physicality of his young bride Euphemia Gray, as she confronts him on their wedding night with her post-pubescent body. The film tacitly endorses the notion that Ruskin was rendered impotent by the sight of female pubic hair, being accustomed only to the frozen marble bodies of classical sculpture.

I don’t believe that for a second. In his recent book, Marriage of Inconvenience, Robert Brownell claims that Effie was something of an adventurer, encouraged by her importunate family to marry Ruskin to forestall her father’s bankruptcy. Far from being disgusted with her physicality, Ruskin – a rigorous Christian and idealist – felt anxious and subconsciously betrayed by the realisation that his love for Effie was a one-sided affair. For him, there simply could be no sexual consummation without the moral exchange of love. Anything else would have been dishonest. And when Effie sued for annulment on grounds of his impotency, Ruskin was too gentlemanly to argue.

Nor is this the only calumny Ruskin has suffered. Despite having been the prophet of his age, the best art critic this country has ever produced, the patron of the pre-Raphaelites and of Turner, his legacy has been reduced to one of a bearded reactionary who, in 1878, accused James Whistler of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” when confronted with the American painter’s avant-garde nocturnes.

But turn that quote around for a minute. Wasn’t it an accurate, kinetic description of an action painting before its time? When the attention-seeking Whistler sued for libel, the action landed Ruskin back in court. Whistler won, but was awarded risible damages of one farthing. He went on to accrue yet more fame on the back of the publicity. Ruskin suffered one of the nervous breakdowns that would contribute to his eventual insanity.

Why can’t we cope with Ruskin’s genius? He was an astonishing figure, as Tim Hilton’s magisterial 2002 biography of him proves. He was a great artist in his own right: his watercolours of Swiss mountains and nature studies speak of an extraordinary brilliance, made more passionate by their creator’s intent. Ruskin put art into practice. He was a utopian who devised the Guild of St George, a celebration of workmanship that underpinned the Arts and Crafts movement of William Morris. He was, above all, a great educator. In his bravura lectures in Oxford, he used giant blown-up watercolours of nature studies thrown on to screens by limelight, more akin to Andy Warhol’s Flowers. These events became performances in the same way that Joseph Beuys’ blackboard lectures would a century later.

The Stones of Venice, Ruskin’s bestselling book, styled an entire century. Indeed, he blamed himself for the endless gothic terraces that coursed through Victorian suburbs. Modern Painters, his volumes of criticism, reinvented the way we saw art. Their rebooting of critical theory is still cited by such discerning critics as Michael Bracewell, acclaimed author of The Space Between: Selected Writings on Art. “Ruskin’s passionate championing of particular artists paved the way for such great later critics as David Sylvester and Robert Hughes,” Bracewell says. “Such erudition, clarity and richly opinionated rigour is sorely missed in contemporary art criticism.”

Ruskin was a visionary, more the progeny of William Blake than a member of the Victorian establishment. He foresaw climate change in The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century – both as a physical threat, in industrial pollution, and a metaphysical one, as a “plague cloud made of dead men’s’ souls”. He despised capitalism and influenced the early Labour party more than Marx, a legacy embodied in the Oxford college founded in his name. His work inspired a new generation in the 20th century: ordinary people of my father’s generation, men such as Philip Ashurst, a Coram hospital foundling and later shop steward, who was introduced to radicalism by Ruskin’s writings.

Although he disdained new technologies such as the train, Ruskin did not reject other advances. He advocated the new medium of photography, and in his monthly newsletter to the working man, Fors Clavigera (Fate’s Hammer), he created what was in effect a 19th-century blog. Sitting at his desk with a pile of newspaper cuttings by his side, he worked through the day’s stories to surreal effect, creating new juxtapositions of imagery that augur the work of the modernists and even, perhaps, William Burroughs’ cut-ups. Even now, this writing seems bizarre and shocking. Debating the nature of the soul, he mused: “I don’t believe any of you would like to live in a room with a murdered man in the cupboard, however well-preserved chemically; even with a sunflower growing out at the top of a head.”

This was a man who defied the expectations of his age. Like his pupil Oscar Wilde – who willingly dirtied his pale hands in Ruskin’s campaign to mend roads in Oxford as a demonstration of the dignity of labour – he was his own invention. One key detail that both Leigh and Thompson get right is the ever-present cornflower blue necktie Ruskin wore, knowing that it highlighted his blue eyes, along with a brown-velvet-collared greatcoat. They were as much his trademarks as Warhol’s wig, or Beuys’s homburg hat.

Indeed, he continues to inspire more thoughtful contemporary artists, such as Tania Kovats, Jeremy Millar and John Kippin, while the Ruskin School of Art has recently recreated his Elements of Drawing as a digital resource. Paul Bonaventura, curator at the school, acknowledges that to some Ruskin’s writing seems “illogical, self-contradictory and just plain silly”. But, says Bonaventura, that’s missing the point: “One goes to Ruskin for the power of seeing. The sustained, inquiring scrutiny of visual experience, the incisive glance and vivid insight; these are the things for which he is rightly celebrated.”

Some might regard this as rearguard action in the face of conceptual art. But Turner prize-listed artist George Shaw – whose intensely painted scenes of inner-city decay might be the product of a modern-day Ruskin, although not his shaven head and Ben Sherman shirts – is not taking this lying down. “Ruskin-bashing has become something of a bloodsport for the nobs and yobs of the contemporary culture machine,” he says. “It’s because he’s fucked up and commentators are obsessed with frailty – it’s their version of the Jeremy Kyle show and it allows them to put the boot in.”

Shaw has been a fan of Ruskin since childhood. “I admired his seriousness and saw him as something out of the Old Testament, forging ahead and pointing the way madly into the new world. He was fur coat and knickers because he could draw better than the artists he championed. I’d like to see today’s blabbermouths try that. Isn’t he a Victorian Warhol, on the edge and in the centre at all times? And like Warhol, he saw his own philosophy and his belief not within himself but in the world around him.” Barely drawing breath, Shaw cites a painful image of Ruskin “as a wounded animal searching for cover in a re-created world”.

On the shores of Coniston Water, perched like a Wagnerian fantasy over the gun-metal Cumbrian lake, stands the physical embodiment of Ruskin’s outsiderdom: Brantwood House. Its Ludwig-like atmosphere is enhanced by the gilded steam barge by which one sails across to Ruskin’s retreat, ascending the banks to the manse. Once inside, the full force of Ruskin’s personality hits you. Everything in its interior – from the cabinets of shells and minerals to the paintings on the walls and the tapestries embroidered with his motto: “There is no wealth but life” – is an expression of this ultimate collector, a man who sought to catalogue our experience of the world and the way art attempts to portray it. Wonderingly, you wander upstairs and into the sanctum of his bedchamber. The room is lit by an oriel window, forcing the lake light into the room, as if it might conjure up a hologram of its tenant.

If it did, it would be a disturbing sight, since this is where Ruskin went mad. It happened one night, as devils danced on his bedpost: he looked out to the lake and finally lost contact with the real world. This last crisis came at the end of another traumatic love affair. He had fallen in love with Rose La Touche when she was barely 10 years old, and he in his 40s. He had pursued her, as she turned of age, to her parents’ horror. Barred from her company, he would chase her carriage through London, at one point confronting her in the Royal Academy and handing her a forbidden love letter. Just as the affair with Effie Gray had begun in hope and ended in disaster, this last relationship concluded even more finally. Rose, psychiatrically disturbed and suffering from anaemia, died at the age of 24. A grieving Ruskin sought the services of mediums to conjure up her spirit; as he began to lose his senses, he believed they had been married, with Joan of Arc as their bridesmaid.

Art could not retrieve Ruskin’s sanity, but it remained his consolation. Under Coniston’s Turnerian skies, he would lie in the bottom of his boat and watch the clouds. He was a burnt-out wreck, a shuffling figure with an ever wilder beard, his pale blue eyes fading – a great evangelist struck dumb. Yet he remained the greatest cultural commentator of his age, because he stood apart from it, and saw it with clarity. A man of such ferocious spirit should not be remembered as a reactionary prude. Far from caricature, Ruskin demands, now more than ever, our absolute praise.

• Philip Hoare will be speaking at the Bournemouth Natural Sciences Society on 8 October at 7.30pm.