The strangest and most beautiful moment in this perversely enlightening exhibition at the British Library comes among photographs of people made up like death, driving hearses and posed like Mr and Mrs Dracula for the annual Whitby Goth Weekend. While these modern goths flaunt their macabre styles, a pale white dress floats nearby like a phantom. It is a gothic dress made in 1816.

This fantastic sartorial survivor from the era when Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein enabled its wearer to consciously dress up as a heroine in one of the gothic novels that were then all the rage. She would have attracted as many curious glances towards her tightly tapered, spire-like sleeves and Sadean waist as someone wearing the black lace Alexander McQueen “Dante” dress that is also in this exhibition. Goth fashions, past and present, express all that makes the gothic so fascinating – and sexual.

In the age when that unknown goth girl was putting on her Bride of Frankenstein dress, the cartoonist James Gillray drew a young woman reading in a genteel drawing room. As she stands in front of the fireplace holding a copy of The Monk by Matthew Lewis (1796), she raises her dress to reveal her naked bum – this is the kind of loose behaviour that gothic novels encourage in their female readers, implies the conservative (but curious) Gillray.

Satirists could sneer all they liked at the gothic craze that fixated Britain in the Napoleonic wars (Jane Austen, who shared Gillray’s Tory suspicion of the trend, brilliantly parodies it in Northanger Abbey, whose heroine absurdly imagines ghosts and kidnappers in an ordinary English country house), but the appetite for dark castles, candlelit shadows and swooning victims was insatiable. In Henry Fuseli’s picture The Nightmare, a young woman is visited in her sleep by grisly monsters that perch on her bed and stare blindly at the onlooker. Yet people sought out such thrills, as we might visit the London Dungeon. A print portrays well-dressed men and women exploring a ruined abbey by candlelight, hoping for ghosts to jump out.

Two hundred years later, Clive Barker’s 1987 film Hellraiser subjected its audience to a journey into sado-masochist tortures from beyond the grave – and they lapped that up, too. The drawings, manuscript notes and poster for Barker’s horror film make drawings by Jake and Dinos Chapman displayed look rather innocent and tame.

For this is not an exhibition about art. It seeks out something more intangible – the nature of imagination.

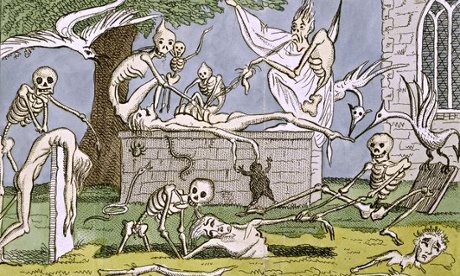

It teems with arresting exhibits, from manuscripts and illustrated editions of novels from Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) onwards, to films, including the terrifying black and white classic Dead of Night, in which Michael Redgrave plays a ventriloquist dominated by his doll, and a display about The Wicker Man that includes an 18th-century book illustrating how the druids burned their victims in giant wicker statues. Through these sensational yet thought-provoking relics, we discover deep continuity in the British gothic mind, from then to today.

But beyond the paraphernalia, we are left with the written word and the flickering image, and their effect on our minds. The gothic happens in us. It’s right to end with goths as a subculture, because they just express outwardly what every horror fan experiences inwardly – a startling liberation of the mind. Why do we choose to enter such macabre realms of fantasy? Why did people in 1890s London look at sensational images of the Jack the Ripper killings – at the time when they were happening – in the London Police Gazette that turned this brutal reality into grand-guignol entertainment? Why do modern audiences still crave gothic shadows when every hokey haunted-house cliche has been done so often?

This epic journey through a literary genre and its endless cultural transformations does not answer that question, but the goths in Whitby and the nameless woman who wore that white dress would probably say the gothic means freedom.