On the way to Bill Murray’s hotel, I keep stepping over bits of his face on the floor. An ear here, a chin there. Damp scraps of cardboard Bill Murray masks litter the streets, evidence of the crowd 48 hours before, huddled against the hail, a sea of identical rueful smiles.

It’s the day after the day after Bill Murray Day in Toronto – 12 hours of archive screenings and costume competitions and a Q&A at which Murray mistook a woman for a man and no one minded. In the evening, the rain came and he squelched down the red carpet for the premiere of his new movie, St Vincent. As the credits rolled and the audience stood, he took to the stage in plastic crown and beauty queen sash and still-sodden suit.

Thing is: if you’re Bill Murray, every day is Bill Murray Day. Every day a Groundhog Day of being treated like a deity. Every morning brings people if not actually wearing your face, then with your features engraved on their hearts. St Vincent’s director, Theodore Melfi, tells me of a time at Atlanta airport when a stranger ran up to Murray and told him how much she loved him. He told her he loved her too and kissed her – hard, on the lips. “It made her life.” Of the waiter in New York who carried around the $50 note Murray once gave him to enrol in an acting class. This is a man whose visitations – crashing a stag do here, rocking the karaoke there – are taken as elusive proof of his divinity. If God was one of us, the logic goes, he’d be Bill Murray.

Official meetings are correspondingly sacrosanct. I’m allotted 10 minutes, stretched to 15 with begging, then 20 through undignified stalling when the publicist comes to fetch me. No more is possible. Off the promo trail, he’s absolutely unavailable – no agent, no manager, no point of contact other than an unlisted 1-800 number on which you can leave a voicemail. I ask Melfi if he might like to share it with me. He laughs.

I wait on a deserted floor at the Trump hotel, sandwiched between two packed ones. The hallowed atmosphere intensifies. After a time, a security guard materialises and discusses the carpet. Then he touches his ear. “Your parcel has arrived,” he says and evaporates. Murray strolls round the corner.

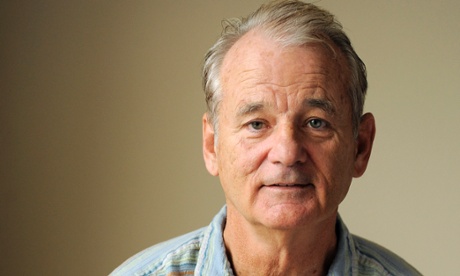

“Well, you look delightful,” he says. “And you smell nice.” He’s wearing blue linen and is very tall. His silver hair is blond at the tips, so when he gives a gummy grin, you think of the baby in the sun on Teletubbies. Later, Tilda Swinton says she thinks he has the look of “a tired child who has laughed so much he aches – but finds it too complicated to fully explain the joke”. That’s true. It’s like talking to a crumpled bag of sweets.

We’re shown to a room and I help him read the Coke bottle label (he only drinks Mexican, on account of the corn syrup). We inspect the facilities. He suggests we take a bath or watch a DVD. Four hardboiled eggs and some fried potatoes are ushered in. He doesn’t touch them.

I have quarter of an hour left. How did he find Bill Murray Day? “OK. Daunting. I was sort of dreading it, I thought it would be so embarrassing. But people seemed to think it was as funny as I did. It was just as good as having a birthday and a great cake and fireworks.” He thinks more. “It was a good day.”

So why do people place such faith in actors? Because what they do seems miraculous? Sure, he says. For him, too. “It’s always a question for me: how are people pulling this off? How can they live with it, how they can be that person up on a screen and then walk down a street or go to a grocery store or drive a car or have a conversation. Like: how does that happen? Where do you get to be superhuman? How can you do it?

“People identify with that. They think: I’d love to be Superman for a while, or be the guy who’s being funny and not taking any guff. I wish I could say that to my neighbour or my wife. You’d like to have that kind of freedom. You go: yeah, that’s what you’re supposed to do. That’s what a hero does.”

In St Vincent, Murray is a familiar kind of hero: the lovable gruff, the mensch in grouchclothing. Vincent is a rude boozer who bets on the horses and has got a Russian prostitute (Naomi Watts) pregnant. He’s mean to new neighbour, single mum Melissa McCarthy. But then he starts babysitting her lonesome son and we twig: he’s great, under the grump.

The movie plays out like Murray’s greatest hits. He sings slurrily and dances funny, cracks wise and rolls his eyes, a dignified clown, brimful of feeling even at his most brittle. Melfi originally courted Jack Nicholson, but when he passed, Murray said he was interested, if he could tailor the script to his strengths.

And Vincent’s emotional journey follows the same arc as Murray’s characters in Groundhog Day and Ghostbusters, Broken Flowers and Lost in Translation. He gets domesticated. The curmudgeon finds salvation in conventionality. “Vincent has got to acknowledge,” says Murray, “that we all have an obligation to more than just ourselves. In this world it plays out as our fellow man. And ultimately something higher – that’s the ultimate we manifest. But the tasks we’re given here are our families.”

Yet Murray’s root appeal is not based on this third-act incarnation. Movies may need to end that way, but off-screen, the closer to average Murray gets, the less we want to be like him. It’s the frank and freewheeling real-life guy we worship, the one who rollicks about dressed like a jumble sale, whose irreverence hasn’t been curbed.

So why does he connect quite so deeply? Cameron Crowe, who’s just finished shooting a movie with him, thinks Murray’s detachment from the star system alters his affinity with an audience. Like the new pope, he walks among us. “He’s very skilled at breaking through the barriers that make many celebrities so uncomfortable around their fans. With Bill and his fans it’s an equal playing field. He’s not floating above them in some hallowed showbiz world, he’s right there with them, living life, like the big brother or uncle you look forward to seeing at Christmas. He doesn’t live in a gilded cage and run from his fans, he runs with them. I think he’s even done that – literally.

“His fame is a fluid, growing thing. Being a fan of Bill Murray never gets boring because he’s not bored, he’s more mercurial and yet somehow more available than ever. In a world where most careers are xeroxes of each other, his is uniquely his own.”

For Melfi and Swinton, Murray’s joie de vivre is key. Swinton recalls him larking about with her children on the set of Broken Flowers, partying the night away with the 12-year-old cast of Moonrise Kingdom in Cannes. He has, she says, “a kind of hopeful aspect; maybe only a trick of the light or something about his look that suggests a constant readiness to play. The sense that no foolishness you could ever admit would faze him. The impression of knowing where the best fun can be found at all times.”

“From zero to 12,” says Melfi, “we were all doing what we wanted to. As we get older we start getting reservations. We live by society’s code of rules – that’s acceptable and that’s not. Bill doesn’t. He lives his life with a complete joy and freedom. And I would desperately love to say: fuck it I’m not going to work today, I’m going to see this band I like. Or I’m just gonna jump on this train real quick, go to Philadelphia and have a cheese steak.”

It’s only Harvey Weinstein – who’s distributing St Vincent in the US – who suggests this could come with a kick. Speaking to Variety about being a “born-again Murray-ite”, he said: “It’s a religion, where you can act as badly as you want to people, and they still love you. I used to feel guilty about behaving badly, and I met Bill, and it feels so much better.”

Murray has licence, almost immunity. He’s Teflon in the face of anything even vaguely unsavoury (it’s interesting that in his films he’s often a lothario, but passive, not predatory; more often seduced than seducing). “He has a certain rare animal – snow leopard – quality,” says Swinton. “Kinda dangerous as well as exotic.”

Murray was born in the mid-20th century, the middle child of nine, living in a three-bedroom house in Chicago. Before Second City, before Saturday Night Live, his improv skills were honed round the dining table. Younger brother Joel has said that the aim was to make their father – a slow eater – laugh with his mouth full. (Murray himself has six sons, by a couple of ex-wives, and his conversation sometimes gets snagged on custody.)

His parents were Irish Catholics; one of his sisters is a nun. This conspicuous religion adds to his broad church appeal (there’s a citation from the Christian Science Monitor on his golfing memoirs). You don’t need to ask if his faith is important to him. He talks about how 19th-century candidates risk not getting canonised because the church is keen to push ahead with the likes of John Paul II and Mother Teresa. “I think they’re just trying to get current and hot,” he smiles.

One new saint he does approve of is Pope John XXIII (who died in 1963). “I’ll buy that one, he’s my guy; an extraordinary joyous Florentine who changed the order. I’m not sure all those changes were right. I tend to disagree with what they call the new mass. I think we lost something by losing the Latin. Now if you go to a Catholic mass even just in Harlem it can be in Spanish, it can be in Ethiopian, it can be in any number of languages. The shape of it, the pictures, are the same but the words aren’t the same.”

Isn’t it good for people to understand it? “I guess,” he says, shaking his head. “But there’s a vibration to those words. If you’ve been in the business long enough you know what they mean anyway. And I really miss the music – the power of it, y’know? Yikes! Sacred music has an affect on your brain.” Instead, he says, we get “folk songs … top 40 stuff … oh, brother….”

Murray is loved for being carefree. But face to face he can seem not just serious, but sober, even sensible. People may tweet when he turns up to serve tequila, but I suspect he also spends quite a lot of time quietly reading the paper. Melfi calls him a “deep thinker” who’s gifted him a lot of books about parenting. And today what really fires him up turns out to be seatbelt safety. In particular the 1965 legislation making them compulsory in new cars. For this, he thinks Ralph Nader is “the greatest living American”.

“People thought: ‘Why is this son of a gun making me wear a seatbelt?’ Well, in 1965 I think the number was 55,000 deaths on the highway a year. That’s a lot of people dying. So he’s saved just about a couple of million people by now. It’s crazy! And that’s just one thing he did!

“I mean, they made a movie about the German who smuggled the Jews out. He saved hundreds. Great man. Deserved a movie. Spectacular. Great film and a great human being. But this guy, Ralph – there’s no movies about Ralph.”

His eyes catch light and he leans forward. He could sing Nader’s praises for ever, and starts to try.

“Businesses bitch about this guy and people hate him because he’s trying to make change. He hasn’t become like super-crazy-wealthy or anything and it’s not about his celebrity. He’s really interested in improving the quality of life for the whole world. Not just America the entire world.”

Was he sorry Nader never made president? No, he was depressed that people blamed him for diverting Democrat votes in 2000, leading to Bush’s victory. “You know: that’s Al Gore’s fault! We didn’t all come here to make the world easier for Al Gore. He should have run a better campaign. He ran a lousy campaign. He was the vice-president during the greatest economic boom in the history of the country.”

He shakes his head, sadly. “Political parties work to cripple their opponents. They spend all their time in office trying to paralyse the work of the others. They try to stifle. It’s cruel, cruel.”

The PR is back and my time is up. So: how might things change in the future, I say, gathering my bag slowly.

“Well, eventually something horrible will happen, something dynamic and powerful. It’s going to have to be cataclysmic for people to wake up and say: ‘OK, is anyone gonna do this?’ There’s going to have to be a shock of another kind.”

I have to stand now, but don’t want to walk away in case he stops speaking. But he rises too, and I’ve misjudged the distance between our seats, so we’re inappropriately close and I’m eyeballing his nipples. It’s intense, but I keep quiet and keep rooted and he keeps talking.

“I think something’s gonna have to change. Usually it’s something like war or 9/11 that makes people come together.” The shooting of Gabrielle Giffords might have been a rallying point, he thought. “Because that’s just a nutter going after someone. And that kind of anger builds and creates horrible events like that.”

He smiles as I inch away. “You know, I wish you could hold all of Congress prisoner and they’d get Stockholm syndrome and have to go along with their captors. And their captors would be people who were real true American citizens.”

And now I can leave. Later, Melfi tells me Murray is “on a mission from God to make the world a better place”. And here we have his commandments. I can’t wait: a sea of citizens, storming Washington, all wearing Bill Murray masks.

• This article was amended on 20 November 2014 to correct the spelling of Ralph Nader’s surname

• St Vincent is released in the UK on 5 December