If politicians can be drunk on power, the equivalent for the technology industry is being drunk on your own disruption, when your confidence in knowing better than established industries, regulators and even governments risks tipping into hubris. The biggest technology companies, including Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook, are increasingly intertwined in our digital lives, particularly through the phones in our pockets. These devices are also enabling a wave of technology startups, from streaming music services such as Spotify to cab-hire apps such as Uber, to build their businesses. But the big technology firms are also becoming powerful cultural gatekeepers, influencing the way we discover music, books, films and news.

There are many things to admire about this, but it is troubling when technology companies use these powers as leverage in disputes with creative industries or present regulations threatening to limit those powers as unfair.

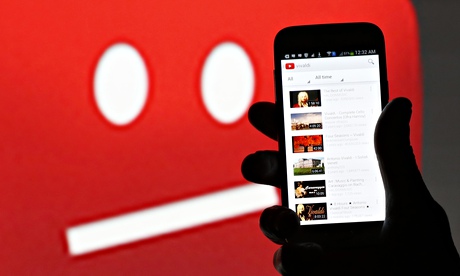

A current dispute between independent record labels and YouTube, the Google-owned online video service, is instructive. YouTube is to launch a subscription music service later this year as a rival to Spotify, Deezer and Apple-owned Beats Music. Traditionally, music industry rights-holders have been portrayed as arrogant dinosaurs clinging to outdated business models in the face of fleet-footed internet innovation. In the latest row, though, the indie labels see themselves as David to YouTube's Goliath.

Trade body WIN claims that YouTube has signed lucrative licensing deals with the three major labels while sending non-negotiable contracts with inferior terms to independents, backed by the threat that if they don't sign up to the paid service, it will block their videos from its existing free one.

That would be a potent threat. YouTube has more than a billion visitors a month and is already the world's largest streaming music service, albeit with that music delivered mainly through videos rather than audio. Being blocked would damage small labels in particular. YouTube claims it is offering fair rates to labels, while confirming that it will block some videos from companies that decline its new service. WIN and fellow trade body Impala are filing a complaint with the European Commission and calling for politicians and musicians to lend it their "slings" for the battle.

This is not an isolated case. Amazon is under fire for halting pre-orders and delaying shipments of books from publisher Hachette and films from Hollywood studio Warner Bros, amid reportedly hardball negotiations over their distribution deals. For Amazon, fewer sales of JK Rowling's new novel or The Lego Movie DVD are a trifling matter – it has plenty of other books and DVDs to sell – but even for large media companies such as Hachette and Warner Bros, Amazon is an important enough distribution partner for the tactics to bite. The wider issue here is one of large technology companies as cultural gatekeepers, with a significant influence over our consumption of music, books, films and other media .

Google's Android software powered its one billionth device in 2013, with research firm Gartner suggesting it will ship a billion more in 2014 alone. Apple has sold more than 800 million devices running its iOS software, while Amazon has just unveiled its first smartphone, the Fire Phone. All three companies already sell tablets and all have a longstanding desire to control televisions in the living room too. These companies are cultural gatekeepers, whether through deciding what entertainment to carry or not carry on their stores and services, or through the algorithms that dictate what content they put in front of us on our smartphones, tablets, TVs and/or web browsers.

The power of recommendation algorithms is a topic that deserves to break out of technology circles. Streaming TV and films service Netflix, for example, says 75% of its subscribers' viewing choices come from its personalised homepage recommendations. The topic applies to social networks too. Facebook says its average user could see 1,500 new items a day in its news feed from friends, brands and media. Its news feed algorithm filters this down into the 300 stories deemed most relevant, but its exact workings are as much of a carefully protected secret as the algorithms governing Google's search engine results – or the details of YouTube and Amazon's licensing deals.

Our relationship with the large tech companies is based on trust: we trust Google to serve us the most relevant search results ; we trust Facebook to understand which friends' status updates are worth seeing; young people in particular trust YouTube as their TV replacement.

We trust… but we don't really understand these algorithms, much less whether other commercial and/or cultural considerations are influencing them. YouTube v indies and Amazon v Hachette are salutary reminders that we should be asking more questions about how technology companies flex their muscles.

We hold politicians to account to ensure they are not drunk on power and we should do the same with technology companies. It's a principle that applies beyond music and books: the tax affairs, employment practices and privacy policies of the most powerful technology companies have all been fair game for scrutiny in recent years and that will continue.

The disruption wrought by technology companies of all sizes can be a powerful and necessary force, but there are often nuances missed (or wilfully ignored) by the more evangelical wing of the tech industry. Uber, for example. A growing number of people love the ability to book a cab, pinpoint its location and pay for their ride from a smartphone and in many cities the startup is offering much-needed competition to entrenched taxi cartels. And yet… Uber faces deservedly rigorous questions about its tax policies – recent accusations that it minimises its tax arrangements in the UK – the transparency of its "surge" pricing and whether its process for vetting drivers meets regulations to protect people.

EC vice president Neelie Kroes has spoken about these nuances: the necessity of technological disruption alongside the fact that "these people all need to pay their taxes and play by the rules". Sometimes the rules are bad and need reforming. And sometimes technology companies think they are above good rules. The better we understand their beliefs and business practices, the better we can hold them to account. And that, in itself, will help us understand when their disruption is positive and important. Which it often is.